In 1988, Liang Shaoji used silkworms for the first time as his media for creation: when he placed the dried cocoon on the fragile silk, the mottled glimmer reflected through it, the subtle shadow of silk and the dry cocoons entangled and intertwined with each other, like a virtual shadow floating. A sentence from Laozi’s Tao Te Ching occurred to him: “Seemingly, there are phenomenon; as if there are things...” “Then why don’t you create living silk works in the virtual and dynamic context?” Therefore, Liang Shaoji started to experiment.

In September 2018, Liang Shaoji’s named his latest solo exhibition at M WOODS by As If. It is a survey of his representative works from the 1990s to the present day and it is also his first solo exhibition in Beijing in the last decade. Featuring six new pieces, the exhibition spans the entirety of the museum and comprises of sculpture, installation, video work and photography. Talking about the scene that flashed into this mind thirty years ago, Liang Shaoji has incorporated a more abundant life experience into his comprehension of “as if”, the Chinese character of “恍”, the left part means “heart” and the right part means “light”, the connection between them indicates the process of experiencing, pursuing and bathing in light thoughtfully.

During the recent decades he has returned to Tiantai Mountain where Liang Shaoji has been raising silkworms there. Recently, during the lecture he gave at the Central Academy of Fine Arts he has summarized his “Six Principles of Creation” from his art practices. First of all, the interaction between Nature and humans; secondly, mediation on “I am a silkworm” with a living perception; thirdly, the association and construction between the silkworm and Zen, the thinking and poetry of silk; fourthly, observing science with artistic eyes while observing art with a living perspective, which means the combination of art and science, rationality and fortuity; fifthly, observing and reflecting on Nature; last but not least, from micro expression to a reflective macroscopic view. “My art stems from my concern with ecology, life, ecological environment and contemporary ecological aesthetics, thus I emphasize the interaction between Nature and humans, as well as the spacial changes in the process of artistic production and biological thinking,” said Liang Shaoji.

“Silkworm is the apostle of light”

Liang Shaoji constantly replied to questions about life. “All beings on the earth are looking for their own living space in the ridiculously inconsistent contradiction.” Since “light” symbolizes hope and civilization, and “silkworm is the apostle of light”: silk is fragile but it shows the tenacious will of life, the conviction of life and the endless life connections. Wu Hung once commented on Liang Shaoji’s creative behavior: “We can imagine the struggle, pain and sublimation contained in this transformation of life, all of which have become the feeling and essence of philosophy of Liang Shaoji’s works.”

Stepping into the first floor gallery of Liang Shaoji’s As If, occupies the entirety of the central hall, The Temple (2013-2018) is a monumental installation that bridges notions of eternity, ritual and redemption across religions and cultures. Amidst a darkened interior, a glowing nine meter tall tower is flanked by two rows of silk-covered pyramids beaming light above. The shadows cast by their metal vertebrae onto the ceiling evoke moving clouds and constellations, while the pyramids below are like monuments linking heaven and earth.

Liang created these pyramids by placing his silkworms on their iron understructures, allowing them to shroud the metal in their silk, symbolically embodying life and the sediments of time. The cold metal brings to mind artifice, industry and modernity, and its contrast with the natural softness of the silk that brings to mind the Taoist stratagem of conquering the mighty through the weak. The sharp knots that are interlaced throughout resemble Christ’s crown of thorns from the Crucifixion. This religious connotation is echoed in the iconology of silk itself, which in China contains references to self-sacrifice, generosity, transubstantiation and resurrection. It is further underscored in the layout of the installation, which resembles that of a church interior. Having studied the philosophies of East and West for many years, The Temple and Liang’s other works touch upon themes present across civilizations, reflective of humanity’s shared fate.

“Silk is a presentation of the existence and being in the long journey of time and life”

In the 1980s, Liang Shaoji studied under the guidance of Wan Man, the master who broke the category of traditional arts and crafts from “hanging on the wall” to the modern art category with the concept of “soft sculpture.” “When I crossed the decorative barriers of fiber art and rejected the temptation of the richness of materials, and then returned to the original starting point of the fabric, I found the critical point existed in science and art, biology and biosociology, textiles and sculpture, installations and performance art,” said Liang Shaoji.

Liang Shaoji’s artworks are process based, incorporating movement and life. Creating these pyramids takes several years, and as the pyramids’ silk covers begin to yellow, Liang allows his worms to work and rework them, creating layers and layers of silk that exhibit the passage of time. For Liang, the enduring and powerful pyramid form is closely tied with eternity, while the layers of silk and traces of the worms embedded within suggest transience and a fleeting life. This duality between transience and eternity is embodied in the silkworm itself. While an individual worm lives for only fifty to sixty days, its lifecycle exhibits an endless circle of birth and rebirth.

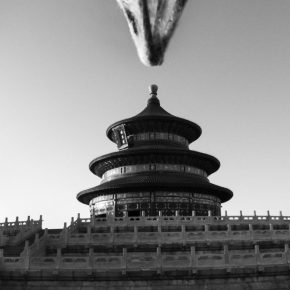

The following two galleries contain works which present Liang’s exploration of the pyramid form and their expressive capacity. Eternity and Time (1993-2018) comprises two pyramids, one on its base and one inverted, which converge at a central point to create an hourglass. Hanging across from this sculpture are works from Liang’s Dialogue series of photographs, in which the artist places his silk pyramids in front of cultural and architectural landmarks such as the Louvre in Paris, the Sagrada Familia in Barcelona, and the Temple of Heaven in Beijing. Through this simple gesture, Liang creates a dialogue between East and West.

In addition, Liang extends his interest in the pyramid form with Fluorescence (2017-2018). To create this work, Liang collaborated with scientific researchers to genetically engineer silkworms capable of spinning biofluorescent silk—the result of a natural protein that glows under specific lighting. Fluorescence is composed of a clear pyramid filled with these special cocoons situated in an immersive cave-like environment. Radiating a mysterious green light and reminiscent of something from science fiction, the work is at once technologically advanced while retaining a sense of the archaic, seamlessly merging ancient and contemporary through an integration of art, nature and science.

Landscape of Silkworms, Broken Landscape and Zen Landscape

For Liang Shaoji, Chinese traditional philosophy is an ambiguous philosophy, as “it emphasizes imagery and spirituality.” From the very beginning of its creation, Liang’s Nature Series permeates the wisdom of Eastern people towards understanding Nature. Contrasting with the grandeur and weight of sculptural works on the first floor, the second accentuates the lightness of silk and its potential for metaphorical association. Raw silk, fossilized wood, bamboo, river stones, ceramics and other materials miraculously transform into the elements of a Chinese shanshui painting: clouds, snow, earth, water and fire. Presenting several pieces never seen before, Liang returns to themes of redemption and atonement, his singular practice suggesting otherworldly hope.

Living, natural landscapes are evoked in Broken Landscape (2013), a silk hanging that reinterprets and reinvents traditional Chinese landscape painting. Over five meters long and cascading from the ceiling like a waterfall, the work’s sweeping stretch of silk retains all the traces of the tiny creatures that spun and metamorphosed upon it. Their excretions dapple the silk with black dots and regions of yellow and pale brown, resembling a vast, abstracted landscape replete with mountains, flowing brooks, and rolling grasslands. The work is like a Chinese scroll painted by silkworms, documenting the vicissitudes of life and society.

In Liang’s artistic practices over the past 30 years, metaphysical and philosophical thinking and poetic meditation has remained as his clue which leads to his pursuit in the beginning and end of life with the convincing symbolic meaning of silk. “Silk is transcending the surface, calling for salvation and producing mysterious waves.” In Liang Shaoji’s creation, we can see that he uses silkworm as a matrix, taking time and life as the core, and interacting with the Nature, taking the whole process of the silkworm reincarnation as a medium. Like silkworms will finally turn into butterflies, Liang Shaoji’s art is also an eternal, endless “emergence.”

Text by Lin Jiabin, edited by Sue/CAFA ART INFO

Courtesy of the Artist and M WOODS