Installation View of‘Italian Renaissance Drawings: A Dialogue with China’

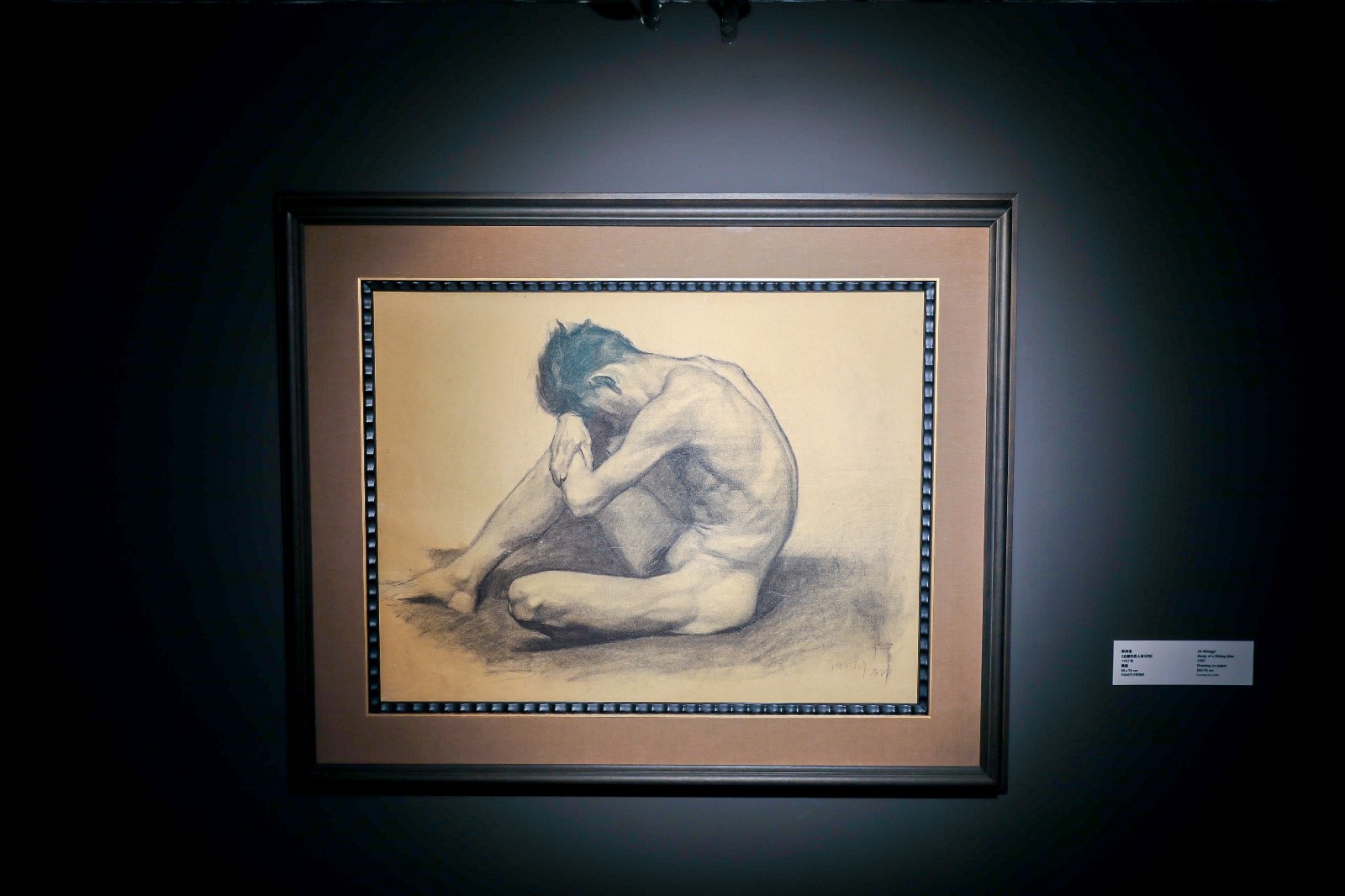

On September 3, the collaborative exhibition ‘Italian Renaissance Drawings: A Dialogue with China’ between M WOODS and the British Museum was held at M WOODS, Qianliang Hutong. This exhibition marked the first project that the British Museum has cooperated with an independent, non-for-profit art museum in China. It aims to enlighten visitors about Italian Renaissance drawings and the highlights of the exhibition include examples by Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo as well as works of many great Renaissance artists such as Titian and Raphael. These works constitute a dialogue with a group of specially selected contemporary Chinese art creations.

Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519), A caricature of an old woman, 1482–1499

Pen and brown ink, Bequeathed by Richard Payne Knight, Courtesy the British Museum © Trustees of the British Museum

The Renaissance artists exhibited in ‘Italian Renaissance Drawings: A Dialogue with China’ mainly came from the Italian peninsula from 1470 to 1580, basically covering the heyday and late stages of the Renaissance. The word “Renaissance” comes from the French translation of the Italian word “rinascimento”, which means “rebirth.” The Renaissance in history refers specifically to the period of cultural and intellectual blossoming that took place in Italy in the 15th century before it spread north of the Alps across Europe. “Rebirth” refers to the renewed interest in ancient Greek and Roman culture when scholars at that time restored and studied Greek and Latin documents as much as possible. A group of new intellectuals who called themselves “humanists” then appeared. They believed that a good education should not only involve the study of Christian doctrine and literature, but it also includes knowledge widely recommended in the pre-Christian world—grammar, rhetoric, poetry, history, politics, moral philosophy, and natural sciences such as mathematics, physics, and engineering.

Polidoro da Caravaggio (about 1500–1536/37), Studies of a youth holding a book, About 1525

Red chalk, Purchased with the support of the National Art Collections Fund, Courtesy the British Museum © Trustees of the British Museum

Why did it take place in Italy? There are many explanations for this. First of all, Italy was one of the regions that had started to develop vigorous business relations during this early period. Cities and states that centered on trade and finance were established, and their leaders were rich, independent, and ambitious. They rushed to hire the most famous artists at that time. Many of the works in this exhibition are related to the Medici Family, the former ruler of Florence; the church is still an important patron of art; many of the Medici were buried in ruins of ancient Rome so the Italians believed that they were the descendants of ancient civilizations and they were more than qualified to revive the legacy of their ancestors.

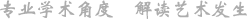

Taddeo Zuccaro (1529–1566), The cultivation of silkworms, 1564–1566

Pen and brown ink, with brown wash, over black chalk, Courtesy the British Museum © Trustees of the British Museum

Humanists favored the pursuit of knowledge itself. The most important thing was that they believed that people should not feel guilty when confronting God as the church in the Middle Ages preached. On the contrary, people were the most perfect creations by God, whose features were rational and creative and they proved the inherent human nobility. Therefore, in the face of God, what people should do was not to tremble and obey, but they should work hard to realize their full intellectual and creative potential.

Gentile Bellini (1429–1507), A Turkish woman, 1480

Pen and black ink, Courtesy the British Museum © Trustees of the British Museum

The significance of these ideas to art was huge. Perspective, light and shade, nature, new aesthetic theories...these elevated painting, sculpture, and architecture to a higher level. Artists were no longer just craftsmen, but they constituted a new special group, whose status ceased to depend on their origins or works, but on their skills. They did not just become the first generation of masters in the West since the Middle Ages, but they also profoundly influenced the formation of the concept of “genius” in aesthetics and art history.

Michelangelo (1475–1564), The Annunciation, 1542–1546

Black chalk, Courtesy the British Museum © Trustees of the British Museum

In the first part of the exhibition, visitors will be able to see how Michelangelo presents and expresses his skills in The Annunciation: the body of the Virgin Mary maintains a stable balance in the dynamics of the shoulders and waist; the image of angel has been repainted many times, and the lines of black chalk (a material made of a mixture of charcoal and clay) interlace on the top of the image, showing us realistically and concretely how this master thinks about his own work. In the “Narrative” part, it shows how artists re-observed the natural world and tried to reproduce nature and the human body in a precise way, and how they represented traditional religions and historical events as realistically as possible. The carefully portrayed human movements, the believable deep spatial background with a linear perspective, stable or moving pictures all show how Renaissance artists valued “design”—this term encompasses a series of complicated processing techniques and organization principles which put forward outstanding requirements for rationality and sensibility—some of these principles still play a fundamental role in art education nowadays.

Raffaello Sanzio, called Raphael (1483–1520), Hercules and the Centaur, 1505–1508

Pen and brown ink, on light grey-brown prepared paper, Courtesy the British Museum © Trustees of the British Museum

Another masterpiece is Hercules and the Centaur by Raphael. This drawing that was printed on the exhibition poster clearly shows the status of the nude in Renaissance art. The nude has again become an important part of painting as the human body was considered to be the noblest creation by God. Artists carefully observed models and learned anatomy, active explorers like Leonardo da Vinci (two of his miniature heads are displayed in the exhibition) even dissected the corpses by himself. Michelangelo is especially renowned for his solid and powerful nude drawings. From this sketch by Raphael, his learning from Michelangelo, this older predecessor, can also be detected.

Rosso Fiorentino (1494–1540), A nude woman sleeping, About 1530-1540

Red chalk, Bequeathed by Richard Payne Knight, Courtesy the British Museum © Trustees of the British Museum

For artists that lived in the Renaissance period, “drawing” was not a creation from a strict sense. Some of them were created for daily training, and some were sketches for larger-scale paintings, murals, and sculptures. Most artists did not intend to share them with others other than their colleagues in the workshop, which added an additional appeal to the exhibition: spectators are able to understand a daily work routine by these artists, as if they had glimpsed the secrets that the masters had carefully hidden.

Installation View of‘Italian Renaissance Drawings: A Dialogue with China’

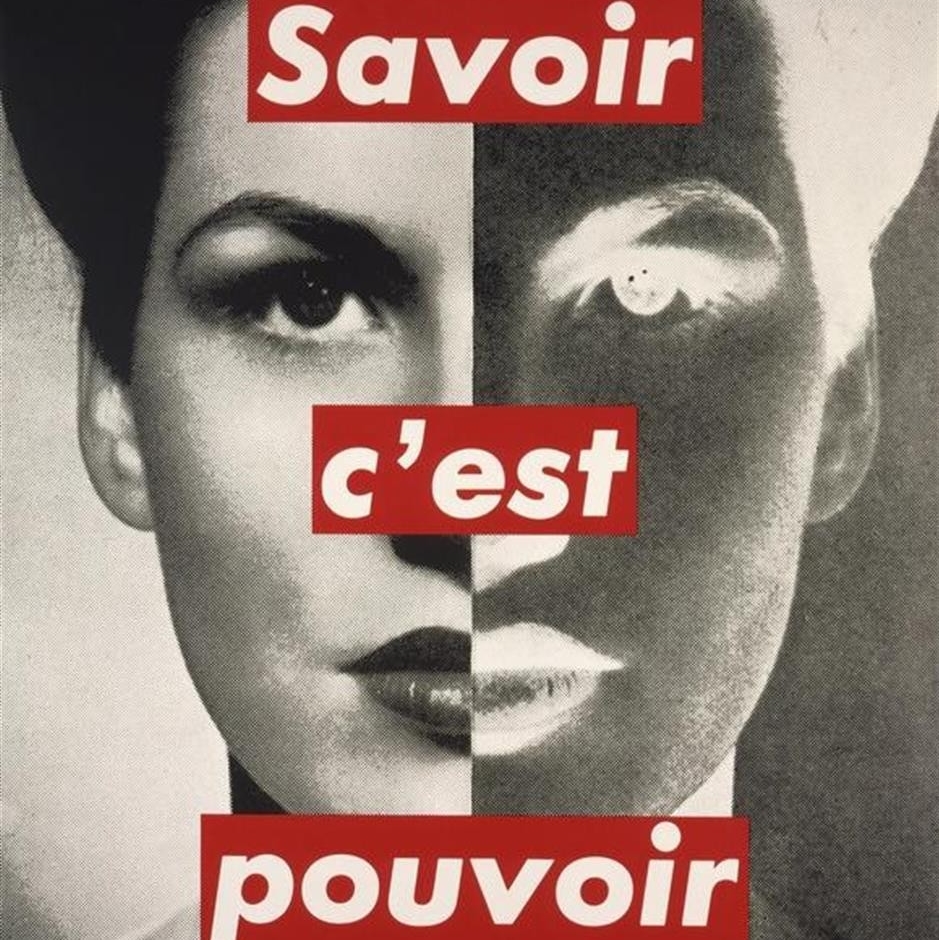

However, the organizers of this exhibition have a greater ambition than “relocating international treasures to China.” Wang Zongfu(Victor Wang), Artistic Director and Chief Curator of M Woods and Sarah Vowles, Curator of the British Museum, tried to think about the Renaissance in a broader context besides Europe in the process of jointly curating the exhibition— in the hope of re-examining these historical works from a cross-cultural perspective across the world. It is the first time in history that these works have been juxtaposed with Chinese contemporary art, and it aims to explore the important connection between the Western Renaissance and China across time and space. While examining this period and the thoughts formed from an expanded historical research perspective, it tries to reveal the relationship between the European Renaissance and Chinese modernization.

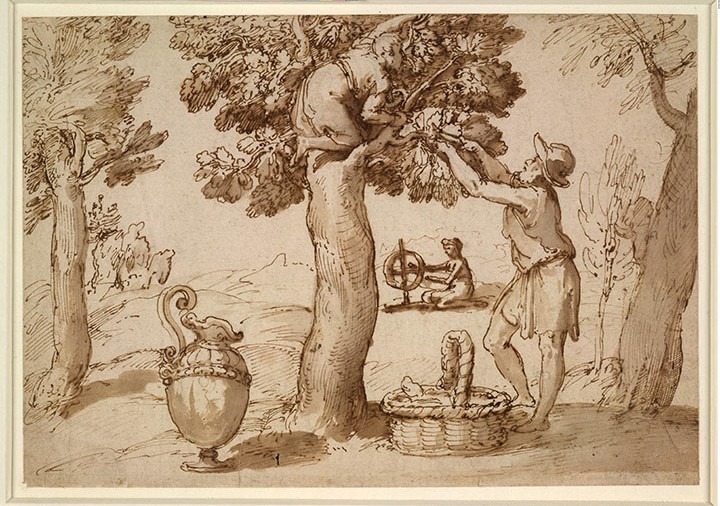

Jin Shangyi, A Sitting Nude Man, 1957, Drawing, Photo Courtesy M WOODS

These endeavors are reflected in the initial part of the exhibition. First of all, spectators need to walk down to the underground gallery through a long and narrow staircase, where the undecorated concrete walls and low ceiling are reminiscent of archaeological expeditions. Here are some of the achievements of modern Chinese scholars’ translation and introduction of the Renaissance since the Republic of China. In the words by renowned intellectuals such as Hu Shi and Liang Sicheng, the Italian Renaissance has become an important reference for the national renaissance of modern China. The sketches by Jin Shangyi and Zeng Fanzhi indicate how the Renaissance, a classic paradigm in Western art history, has been regarded as a universal reference object by artists since the founding of People’s Republic of China (although the creative paths may be completely different)—just like the Renaissance artists copied classical works, and all art education in Chinese academies of fine arts have studied and copied the reproductions of Renaissance masterpieces. The other Chinese contemporary art works in this exhibition are also displayed by following the same concept. The detailed description of each work does not only show the complicated continuity and diversity between contemporary China and the ancient West, but they also jointly try to reposition and evaluate previous works in the history.

Installation View of‘Italian Renaissance Drawings: A Dialogue with China’

Due to the requirements of the cultural relic protection (old paper is more sensitive to light than cloth and other materials), the lights in the exhibition galleries appear dim, which also strengthens the sacred nature of these works as browsing becomes objectively ineffective. In reality, viewers must get closer to observe the details in the work, some of which need to be observed by a magnifying glass. The design of the exhibition hall also consciously reinforced this. A temple-like space was built in the center of the largest exhibition hall and in the center of the shrine was another manuscript by Michelangelo. In any case, people come here to visit drawings by the Renaissance masters. Audiences who have received art training will be quickly attracted to these precious details, and the general public can quickly intuitively feel the mythical strength of art from the exhibition. As for whether a further dialogue can be established, it may ultimately depend on the independent thinking of each audience.

It is reported that this exhibition will remain on view until February 20, 2022.

Text by Luo Yifei, translated by Sue/CAFA ART INFO

Photo Courtesy M WOODS.

Curator Wang Zongfu(Victor Wang) introduced the exhibition.

Exhibition View of‘Italian Renaissance Drawings: A Dialogue with China’

About the exhibition

Dates: 3 September 2021 - 20 February 2022

Curated by Victor Wang, M WOODS, and Sarah Vowles, the British Museum

The presentation of this exhibition is a collaboration between M WOODS Museum and the British Museum.

Works from the British Museum Collection by: Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, Titian, Raphael, Polidoro da Caravaggio, Lorenzo di Credi, and more.

In dialogue with artists: Hao Liang (郝量), Hu Xiaoyuan(胡晓媛), Jin Shangyi (靳尚谊), Kan Xuan (阚萱), Liu Xiaodong (刘小东), Liu Ye (刘野), Qiu Xiaofei (仇晓飞), Xie Nanxing (谢南星), Yu Ji (于吉), Zeng Fanzhi (曾梵志)