Fu Xiaotong

Artist Statement

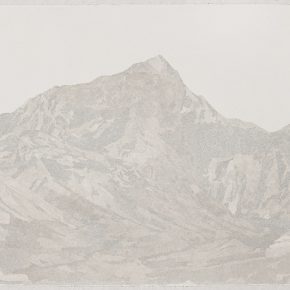

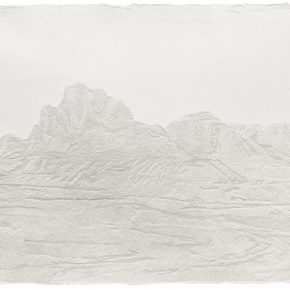

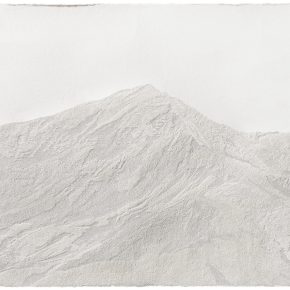

By Fu XiaotongI started to use needles to make holes on Xuan paper (a kind of handmade rice paper invented in ancient China used for writing and painting) in 2010, when I was a postgraduate student in the Department of Experimental Art at the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing, where my professor asked us to explore the wealth of possibilities in a single material. The exercise of testing various mediums made me aware of the intrinsic characteristics and essence of each material. In the end, I chose handmade Xuan paper to be my primary medium and decided to use needles to pierce holes in the paper in order to form images. Traditional Chinese Xuan paper is made of natural materials such as bamboo, grass, and tree bark; it is soft, delicate, and pliant. The ancient Chinese were known for their worship of Nature and had special feelings towards this paper, which they appreciated for its vitality. The delicacy of Xuan paper reminds the Chinese that life is similarly fragile and elusive, its apparent strength easily torn apart like a piece of paper. I have always believed that to cover the Xuan paper with ink and paint undermines its distinctive characteristics, and I hope I can illuminate these characteristics in a different way. I choose the needle as my tool because it does not add any colors to the paper, allowing it to breathe freely; also, I choose it spontaneously from a natural instinct. Certainly, as a traditional tool, the needle has many meanings and cultural references. The repeated action of making numerous holes on the paper gives my artwork an enduring quality. These intricate holes form the images of Shan Shui; the needle tip penetrates both sides of the paper over and over, as if casting a spell, indicating the nothingness of images. I use the number of needle-holes in each piece to name each work. In doing so, I hope to dissolve my individuality. Perhaps, this is the best way for me to protest against despair and solitude, hiding behind an extreme approach and artistic vocabulary.

Nühua—Khôra—Minimalism

A (Sub-)Tract (from/)on the Work of the Artist Fu Xiaotong

Paul Gladston with Lynne Howarth-Gladston

This article was originally published on Eyeline Issue No. 86, 2017, Australia, www.eyelinepublishing.com.

The best of man [sic] is like water,

Which benefits all things, and does not contend with them,

– the Daodejing

I

In front of us on a table-top are photographic representations of works by the artist Fu Xiaotong. Most represent sheets of paper that have been pierced multiple times in such a way that the resulting interventions upon the paper’s surface give rise to depictions of mountain landscapes, flowing water (both subjects traditional to Chinese ink and brush painting) and abstracted natural forms. One of the works depicts the Jokhang Temple in the Tibetan capital, Lhasa. A statement by Fu accompanying the reproductions of her work informs me that the material employed in their making is Xuanzhi—a handmade paper used traditionally in China as a support for painting and writing with ink and brush whose main constituent is pulped elm tree bark sometimes supplemented by pulped rice, bamboo and mulberry—and that the paper was pierced by needles more usually employed by Chinese women in the production of textiles and needlepoint.

II

Xuanzhi, or Xuan paper was first manufactured in China during the Tang Dynasty (618-907) in Jing County under the Xuan Prefecture (Xuanzhou), from where its name derives. Among the first documented references to Xuan paper are those included in the New Book of Tang (Xin Tangshu), an official ten-volume history of the Tang Dynasty written during the Song Dynasty (960-1279). There are three grades of Xuan paper: shengxuan (literally ‘raw Xuan’), which has a relatively unrefined highly absorbent surface that blurs the edges of water-based paint or ink marks applied to it; shuxuan (literally ‘ripe Xuan’), which is processed using potassium alum resulting in greater stiffness, smoothness of surface, reduced absorption and greater ease of tearing; and banshuxuan (literally ‘half-ripe Xuan’), with properties somewhere between the first two. Because of its relatively high absorbency, shengxuan is used traditionally in China as a support for looser xieyi (‘sketching thoughts’, otherwise known as shui-mo) ink and brush painting, while shuxuan is used for more detailed and meticulous gongbi painting. Xuan paper is extremely durable. Many of the paintings and documents that have survived in China since antiquity were produced using Xuan paper. The addition of mulberry to Xuan paper deters destructive infestation by insects and beetles.III

China’s traditionally all-male scholar-gentry class (wenren)—including the sub-set of that class known as the Literati (Shi dafu), who acted as imperial civil servants from the Han Dynasty (206-220) until the founding of Republican China in 1911-12—were trained, as a matter of convention, in the ‘four arts’: playing of and composing for the stringed musical instrument known as the qin; playing of the strategy board game qi (now referred to in China as weiqi and in Japan and the west as go); shu, calligraphy involving the use of ink and brush on paper or silk; and hua, painting also using ink and brush on paper or silk. The four arts are associated historically with an adherence to Confucian ethics and filial piety, which in principle underpinned the scholar-gentry’s moral-critical commitment to the stability and continuity of the Chinese Imperial state. Wenrenhua—painting produced by China’s (in principle, though by no means always in practice, strictly amateur) scholar-gentry class—is synonymous with the technique known as xieyi or shui-mo. Shan-shui (literally ‘mountains and water’) landscape painting produced using xieyi began to emerge as the highest form of wenrenhua during the Song Dynasty.

IV

Wenrenhua is not only understood to embody worldly Confucian values, but in addition traces of the non-rationalist cosmological outlook of Daoism—as signified by the well-known taijitu or yin-yang symbol—aspects of which were co-opted as formative constituents of Confucianism and Chinese Chan Buddhism. The development of elite literati culture in the so-called Jiangnan region south of the Yangtze River from the Song Dynasty onwards has been contrasted historically with supposedly more formal cultural attitudes dominant in the north of China, especially in and around Beijing, China’s principal capital since the fifteenth century. This perceived regional difference is strongly informed by a shift in aesthetic outlook among the scholar-gentry at the beginning of the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368) following their ejection from the imperial court by invading Mongolian forces. The ejection of the scholar-gentry from the imperial court by the Mongols resulted in the development of a distinctively abstracted and subjective style of xieyi wenrenhua in contrast to the formally harmonious and meticulous gongbi painting favoured by professional artisan and court painters. From the thirteenth century onwards wenrenhua came to be seen as the principle means of individualistic expression among China’s scholar-gentry. Practised though spontaneous application of line as part of the production of wenrenhua became not only a sign of scholarly refinement and Confucian-moral rectitude, but also—in accordance with the Daoist precepts of wu wei (action through non-action) and ziran (naturalness)—of an elevated separation of self as a cultured individual from others; a seemingly paradoxical combination of individualism and subservience to rigid social order redolent of Confucianism’s somewhat contradictory appropriation of non-rationalist Daoist thinking.V

As Fu’s statement indicates, she first began to produce artworks using needles to pierce Xuan paper in 2010 during her studies as a masters’ student in the Department of Experimental Art at the Central Academy of Fine Arts, Beijing. Fu’s use of needles to pierce Xuan paper developed as a result of an exercise in which students were asked to explore the intrinsic properties of differing materials. Piercing rather than painterly or graphic mark-making enabled Fu to exploit the specific durability and elasticity of Xuan paper as a means of depicting form. Carefully considered repeated piercings of Xuan paper with needles used traditionally in China as part of the production of textiles and needlepoint produced graduated material disruptions of surface giving the illusion of (by making actual) light reflected by forms in space. Fu believes that ‘covering’ Xuan paper with ink or paint ‘will undermine its distinguishing characteristics’. Her intention is to ‘illuminate these characteristics in a different way’; choosing needles as tools because they do not ‘add any color’, allowing ‘the paper to breath freely’.

VI

Qi (literally ‘breath’) is upheld by pre-Daoist and Daoist texts as the cosmological condition of the possibility of all being (the structure of ‘myriad things’). As such, qi, which manifests itself through potentially harmonious interaction between cosmic opposites signified by the pairing yin-yang—respectively, that which turns away from the light (female principle) and that which turns towards the light (male principle)—is understood as having no definitive ontology. As Zhang Dainian makes clear,In popular parlance qi is applied to the air we breathe, steam, smoke and all gaseous substances. The philosophical use of the term underlines the movement of qi. Qi is both what really exists and what has the ability to become. To stress one at the expense of the other would be to misunderstand qi. Qi is the life principle but is also the stuff of inanimate objects. As a philosophical category qi originally referred to the existence of whatever is of a nature to change. The meaning is then expanded to encompass all phenomena, both physical and spiritual. It is energy that has the capacity to become material objects while remaining what it is. It thus combines “potentiality” with “matter.” To understand it solely as “potentiality” would be wrong, just as it cannot be translated simply as “matter.” 1

In short, qi is both ‘being’ and ‘beingless’. With regard to the cosmological pairing of yin-yang, ‘beingless’ is conventionally aligned with the female principle of yin as a matter of endarkened ‘being less’, or more precisely in the context of a historically intensely patriarchal Chinese society no-thing at all.

VII

We sit here at our table making virtual marks on paper in pursuit of an always-already fugitive meaning. The result is an accumulation of glosses: textual fragments falling short of any definitive interpretation that bestow passing lustre but are ultimately misleading.

VIII

In her statement Fu asserts that her use of traditional tools and materials carries with it traces of multiple localized cultural references: a reverence for nature and the elusiveness and fragility of life traditionally embodied by Xuan paper (as something produced from the transformation of natural resources—appropriated to social uses—while remaining ‘easily torn apart’). Fu also asserts that the needle tip penetrates both sides of the paper ‘over and over, as if casting a spell, indicating the nothingness of images’. No suturing thread is drawn through in the wake of puncturing. Representation is made possible by multiple combinatory absences: repeated punctum delens, if you will. As Zhang Dainian reminds us, in traditional Chinese thought ‘what objects lack, for example, a hole, can be termed beingless’. 2 The holes pierced by Fu arise conditionally in relation to the materially enlightened ‘being’ of Xuan paper, thereby invoking a latent potentiality—spectral images made present through a persistent play of presence and absence of reflected light. The potentiality of interaction between being and beingless as well as between that which turns away from and towards the light (yin-yang) may be understood to have been set in motion by the puncturing of surface. It is elision as both omission and conjoining. Is this, perhaps, the ‘breathing’ (qi) of the paper to which Fu refers? Fu uses the number of needle holes produced to name each work; hoping, by doing so, to ‘dissolve’ her individuality—protesting ‘despair and solitude’ hidden behind ‘an extreme approach and artistic vocabulary’.

IX

Fu’s piercing of Xuan paper is in many respects a reversal of techniques associated traditionally with wenrenhua. Instead of applying ink to paper she intervenes negatively, disrupting its very fabric. In place of veiling additions through assured application of line, multiple absences are formed by an obsessively measured accumulation of piercings whose meticulousness is more redolent of gongbi than xieyi painting. Spontaneity and individuality give way to a resolutely non-expressive interruption of the integrity of the paper’s surface. Depiction arises not as a setting out of additive signifiers but as an effect of material disruption. Repetitive piercing by needles—traditionally women’s work—is used to displace (to subtract from and exceed) the additive covering of paper by ink associated with the masculinist Confucianism of China’s historical scholar-gentry. Representation, while consonant with traditional shan-shui subject matter, is revenant. Its appearance is immaterial, at once replete with significance and void (‘the nothingness of images’). Rather than simply appropriating and contending with a historically male-dominated painterly practice, Fu has taken from it, reducing it to its fundamental supporting constituent; thereby remotivating culturally gendered tradition against itself. Where traditional wenrenhua combines (ink on paper), Yu reduces (empties out) through a sustained needle-pricking pastiche of phallocentric plenitude (an excess of significance) resulting in the negation of the latter’s perceived authority. The process as well as aesthetic affect is both meditative (a loss of the desiring self through sustained repetition) and empty of settled meaning/feeling; to borrow from Georges Bataille, it moves ‘like water in water’.3 It is an interruption that problematizes what was thought of in the context of China’s patriarchal-Confucian traditions as the very impossibility of women’s wenrenhua; an aberrant/mistaken category whose potential has now been set in motion by the accession of women into modern/contemporary artistic production as part of the development of republican post-imperial Chinese society. It is also one that manifests itself in historical relation to the prior existence of nüshu 4—a form of writing/calligraphy used exclusively by women since the Song Dynasty in Jiangyong county of Hunan province—and that may therefore be referred to speculatively as nühua. Meaning in this instance is indissociably enmeshed not only with shifting historical context but also the performativity of a distinctly interruptive gendered technique.

X

Fu’s technique is also the antithesis of pouncing, used traditionally by painters to transfer images from one surface to another; first by tracing an image using semi-transparent paper, then by pricking the resulting outlines using a needle or multi-pointed wheel, laying the pricked paper over a new surface and forcing graphite or chalk through the resulting holes to repeat the outlines of the original image. While pouncing uses piercing of paper as a vehicle for the (phallocentric) addition of marks to a surface, Fu’s penetrative technique remains persistently subtractive (while at the same time in excess of settled meaning).

XI

Martin Heidegger refers to khôra—in ancient Greece the territory outside the polis or city proper—as the ‘clearing’ in which being takes place. This conception of khôra draws on Plato’s use of the term in the Timaeus to metaphorically signify a womb-like interval, that is in a state of neither being nor non-being, in which ideal ‘forms’ were originally held. Julia Kristeva appropriates the notion of the ‘chora’ [sic] and its maternal connotations to posit a semiotic state of pre-signification (prior to the symbolic) that is both the conditional substratum of a supposedly phallocentric linguistic symbolism and at the same time the latter’s radical other. 5 In his short essay Khôra 6, Jacques Derrida uses the term to identify the site of the differentiation between being and non-being, which comprehends the possibility of that differentiation while simultaneously resisting identification simply as one or the other. For Derrida, khôra can thus be understood to defy the binary logic of linguistic naming. As such, its own naming may be taken as a supplement to Derrida’s coining of the term différance, which he uses to performatively signify a persistently deconstructive movement of differing-deferring between signs upon which the very possibility of linguistic meaning is conditional. 7

XII

There is an evident conceptual affinity between the notions of khôra and qi. Both signify an ultimately ineffable semiotic ground or opening that constitutes conditions of the separation of being and non-being while at the same time escaping settled definition as one or the other. The identification of khôra with qi is by no means absolute, however. Where the poststructuralist naming of khôra is intended as indicative of an ultimately unresolvable field of signification—one in which the openness of language to unfolding disjuncture results in a persistent deconstructive negation of authoritative meaning through shifting multiplications of significance—qi through its supposed manifestation as yin-yang points conversely towards the metaphysical possibility of a desired cosmic harmony between opposites. Whether we view Fu’s disruptive intervention into the integrity of surface as simply deconstructive of phallocentric authority or as a gesture towards harmonious reciprocation between male being and female beingless is a matter of cultural parallax—that is to say, one’s cultural-discursive positioning in relation to Yu’s work. Commensurate with the potentiality of the interaction between being and beingless which Yu may be understood to have set in motion, the two positions (one deconstructive, the other ultimately metaphysical) either remain irreducible to one another or subject to possible reciprocity.

XIII

The subtractive simplicity and non-expressiveness of Fu’s work suggests an affinity with ideas and practices associated with Minimalism. As Adam Geczy and Jaqueline Millner have argued, minimalism is now one of the signature styles of internationalized contemporary art that bridges differing localized contexts of cultural production and consumption. In their book Fashionable Art (2015)8, Geczy and Millner identify various aspects of internationally dominant artistic discourse and practice, which, they argue, condition prevailing views of what is considered ‘progressively’ fashionable (in both senses of the word) and therefore commercial within the international art world. The aspects of artistic discourse and practice identified by Geczy and Millner in this regard include the ‘artist-impresario’, ‘identity politics’, ‘exoticism’, ‘formlessness’, ‘relational aesthetics’ (and its detractors), ‘video art’, ‘minimalism’ and ‘outsider art’—all of them upheld as established signifiers of the supposed line separating fashionably cool and outwardly-oriented contemporary art from its rather more stick-in-the-mud self-regarding pre-Warholian modernist forbear. It should be remembered, however, that the significance of the term ‘minimalism’ was previously something other than simply that of signature coolness. As Gregory Battock makes clear in the introduction to Minimal Art: a Critical anthology (1968),

Minimal art is not a negation of past art, or a nihilistic gesture. Indeed it must be understood that by not doing something one can instead make a fully affirmative gesture, that the Minimal artist is engaged in an appraisal of past and present, and that he [sic] frequently finds present aesthetic and sociological behaviour both hypocritical and empty. One could object that this attitude is merely a rationalization of an art form involved with nothing but this is not the case. Minimal style is extremely complex. The artist has to create new notions of scale, space, containment, shape and object. He must reconstruct the relationship between art as object and between object and man.9

Here a case is made for Minimalism not merely as a style negatively signifying modishness, but as a site of or opening for the critical-interruptive setting of artistic potentiality in motion. Moreover, one that, in spite of Minimalism’s ostensible withdrawal into reductive formalism, is conceived of as ushering in the possibility of a far-reaching critical reworking of the relationship between ‘art as object’ and society. To describe Fu’s Xuan paper-based works as ‘minimalist’ is potentially misleading insofar as it is suggestive of the cultural-commercial conditioning now attached to the term. Fu’s work does though share in something of the vision set out previously for a minimalist art by Battock. Fu’s subtractive interruption into the very fabric of traditional scholar-gentry painting in China extends beyond that of a simply negative reworking of technical means. It is one that makes disjunctively manifest the fundamental conditions of such painting (by subtracting from it) as a means of projecting the critical prospect of a renewed, less assuredly gender-exclusive relationship between artistic production and society.

Notes:

1. Zhang Dainian, Edmund Ryden trans., Key Concepts in Chinese Philosophy, Beijing: Foreign Languages Press and New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2002, 45-46.

2. Ibid. 161.

3. Georges Bataille, Robert Hurley trans., Theory of Religion, New York: Zone Books, 1992, 23

4. For a discussion of nüshu, see Luise Guest, ‘Secrets, sorrow and the feminine subjective: Nüshu references in the work of contemporary Chinese artists Ma Yanling’, Journal of Contemporary Chinese Art 2:1

5. Julia Kristeva, Toril Moi ed., The Kristeva Reader, Oxford: Blackwell, 1986, 89-136.

6. Jacques Derrida, Khôra, Paris: Galilée, 1993.

7. Jacques Derrida, Alan Bass trans., Margins of Philosophy, London: Harvester Wheatsheaf, 1982, 1-27

8. Adam Geczy and Jacqueline Millner, Fashionable Art, London: Bloomsbury, 2015.

9. Gregory Battock ed., Minimal Art: a Critical Anthology, New York: E.P. Dutton, 1968, 26.

About the authors

Paul Gladston is Professor of Contemporary Visual Cultures and Critical Theory at the University of Nottingham. His book Contemporary Chinese Art: a Critical Historywas awarded ‘best publication’ at the Art Awards China, 2015.

Lynne Howarth-Gladston is an artist, curator and independent scholar. She has exhibited her painting internationally and was co-curator with Paul Gladston of the exhibition New China/New Art Contemporary Video from Shanghai and Hangzhou, which was staged at the University of Nottingham’s Djanogly Gallery in 2015.

About Fu Xiaotong

1976 Born in Shanxi, China

2000 Graduated from Oil Painting Department of Tianjin Academy of Fine Arts, China

2013 Graduated from the Department of Experimental Art, China Central Academy of Fine Arts, China

2001-Present

Lecturer at the Institute of the arts, North China University of Science and Technology, Tangshan, China

Currently lives and works in Beijing, China

Solo Exhibitions

2017 Without end, Chambers Fine Art, Beijing, China

2016 Art Basel, Hong Kong, China

Land of Serenity, Chambers Fine Art, New York, USA2015 Land of Serenity, Chambers Fine Art, Beijing, China

2012 Breathe – Fu Xiaotong Paper Exhibition nine thinking culture of Tianjin, China

Group Exhibitions

2018

San Francisco Art Fair, San Francisco

ArtBasel, Hong Kong

“Art on Paper”, New York

2017

“Art021” Shanghai

Art on Paper 2017 Expo, New York

RECIPROCAL ENLIGHTENMENT – The third College Experimental Art Literature Exhibition, CAFA, Beijing

Organic Chaos, AroundSpace Gallery, ShangHai

2016

The Exhibition of Annual of Contemporary Art of China, Beiing Art Museum

“Paper Presence” Common Art Center, Beijing

AROUNDSPACE 10TH ANNIVERSARY, ShangHai

2015

Ireland Cultural Festival Art Exhibition, Beijing

2014

Polyphony · 21 kinds of state, China

"New visual boundary" A Variety of Media Art Exhibition, China

Biennale China-italia, China

New Acquaintances: Works by Four artists, Chambers Fine Art, USA

Jing Gallery to Unveil the invisible-Pan Jian & Fu Xiao Tong Duo Exhibition, China

“ Room C Plan Second Round”, Shone-Show gallery, China

“confrontion anitya ”oriental experience in contemporary art Exhibition Tour of Germany, France Etc

"Material World"at m50\loftooo gallery, Shanghai

"Legend" of Contemporary Female Art, Louis Vuitton Store in Tianjin, China

2014 New Year Special Collection, Ying Gallery, China

2013

“Nature And Spirit”, Being 3 Gallery, China

“Materials-Substance”, Found Museum, China

“New Paper”, Pekin Fine Arts, China

“Wedge”–Young Artists Exhibition Sui Feng Art Museum of Beijing, China

“Postgraduate Graduation Exhibition” in CAFA Art Museum, China

“Materials-Substance” in CAFA Multiple-function Hall, China

Ireland Cultural Festival Art Exhibition – the Siege and Boundary 798 Art District Beijing, China

Courtesy of the artist and edited by CAFA ART INFO

-2017-mixed-media-variable-dimension-290x290.jpg)