Xiang Jing and Her Work; Photo: www.lifeweek.com.cn

Part I: That’s how people lived, how they perceived the world

Xiang Jing: Your child is about ten now?

Chen Jiaying: Nine.

Xiang: Did you have any children before this one?

Chen: No, this is my first child.

Xiang: In The Irreducible Eidos, I read that you mentioned that you never hoped to live a normal life.

Chen: Right. I never made such a plan. Life is not about making specific choices, but about what you encounter.

Xiang: Having a child must have brought great changes.

Chen: Really great changes…

Xiang: Greater than those brought by marriage.

Chen: Much greater. Nowadays this is certainly the case. In the past, marriage was like a marriage between two families. Now it is just two individuals, which doesn’t seem to lead to great changes.

Xiang: A child is really concrete. It is all of reality.

Chen: In the past, when I traveled, I would seek out places few people. Now I go to the places with the most people. Once I even said that, and my friends laughed at me.

Xiang: But even with a child in tow, you’re still willing to keep traveling everywhere?

Chen: I still run around. I like traveling, so now I just take her with me. It’s good for kids to visit different places. My daughter doesn’t really like to study; she likes to run around.

Xiang: As you take her all over the place, of course she won’t like to study.

Chen: It makes her like it even less, that’s true. Studying is possibly quite important, but it really depends on your nature. You don’t necessarily have to study. For this year’s summer holiday, I am going to take the family to see France. We’ll travel more in China in the future. She’s a child now, but when most kids reach their teens, they don’t like to be with their parents anymore. Most people of my age have children in their twenties. They don’t even know what their children are doing.

Xiang: They’re lucky to get a phone call here and there.

Chen: A lot of the kids don’t talk much to their parents now, but they will talk to us. Parents often ask us what their kids are doing.

Xiang: You’ve traveled all across China?

Chen: Yes. I haven’t been to every corner, but I’ve been to most places. I was about 14 years old when the Cultural Revolution began. After that was the “Big Leap Forward of the Red Guards.” When I first set out for the “Big Leap Forward” I still had the fervor of the Cultural Revolution, but before long I began to take it as little more than a rare opportunity to travel. At the time, I had no idea what would become of China; I just felt that most people spent their entire lives in a single place, and that I should move around. I had my sights set on remote places like Yunnan and Xinjiang.

The 1970s published by SDX Joint Publishing Company

Xiang: How did you travel, by train?

Chen: I took the train, and it took a very long time. For instance, when we went to Urumqi in Xinjiang, the ride lasted for a whole week. When we crossed the Gobi Desert, sometimes the train would climb a hill, and then it would slow down to a walking pace. The train to Urumqi was completely packed. It was hard to sit down and hard to sleep. We helped the dining cart hand out meals, which were little boxes stacked up in bamboo crates. I can’t remember, but I don’t think they charged for it.

Xiang: Did they charge for the train tickets?

Chen: The trains were free as well. Thinking back, it was pretty good: a 14 year old boy carrying a basket of food, wearing an apron to protect himself against the leaking juices. I would push through the crowds on the train as I handed out meals. The head cook and the head officer were very nice to us, letting us stay with the attendants in the dining car. I got along well with them, and they opened the door, letting me sit on the ladder on the side of the train. I sat like that through the Gobi Desert, looking out at the expanse of desert all day. The reason they dared to let us sit there is because the train was going very slowly. You could’ve kept up by just running alongside it.

Xiang: It’s like an old western movie.

Chen: By the end of the Big Leap Forward, I’d been to most of the provinces in China. During my time in the rural production brigade, and later in college, we had more opportunities to travel, but that was just travel to the main cities and tourist sites. It’s not like the big travelers I know, who can spend decades in strange, remote places.

Xiang: My father had a unique experience. He entered college in his teens, and by the time he graduated from the Chinese Department of Xiamen University, he was only 20. He was assigned to work in Beijing. He had always lived in Fujian, and that was his first time to the north, to the capital, so he took his luggage – some beat-up old bags – and mailed them ahead to Beijing. He took a mat and a small bag, and took trains all the way from Xiamen to Beijing. It took him a week.

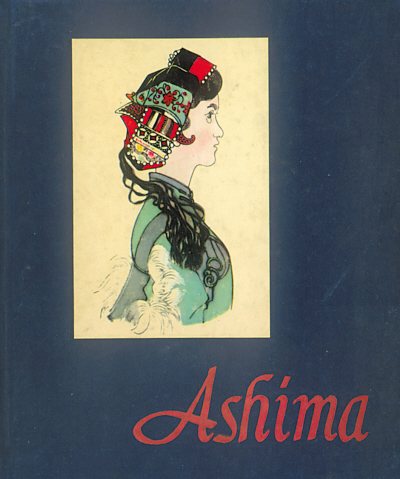

He was assigned to work at the Folk Art Research Society. This was back in the late 50s, and their work was to collect folk songs and unique folk art skills from the various ethnic groups and regions across China, such as folk poetry, storytelling, etc. I bet it was a lot of fun. It was very meaningful work. Even Ashima [an epic poem from the Yi ethnic group], which Huang Yongyu painted the cover for, was the result of their collaborative efforts. They documented a lot of traditions that were on the verge of dying out. Of course, a lot was lost during the Cultural Revolution. Since he was young, he volunteered to do this work, so he was able to travel to a lot of places. It’s very interesting.

The Cover of "Ashima" painted by Huang Yongyu, published by Foreign Languages Press, 1981

Chen: That was a rarity back then. It was only people with special jobs or very special personalities. Most people weren’t like that.

Xiang: He was young and very curious, and so he took on a lot of work like that. When he told me about it, I found it very interesting. I can imagine that China felt very different back then. For the individual, it’s very romantic.

Chen: It really was different. For one, all of the places were different from each other. If you went to Xinjiang, it would be one way, and then Guangzhou would be another way. The second thing, I’m not sure if I’ve written about this, but it deeply impressed me. In 1971 I took a boat from Suzhou to Hangzhou, along the canal. Aside from the light of the waiting hut on the shore, it felt like we were closer to the Tang or Song dynasty, rather than the current day. As soon as the boat left the dock, we entered the reeds, and you couldn’t see the path at all. Of course, the locals knew where they were going, and they had motors in their boats – which is rather modern – but aside from that, it was just the stars and the clouds, without a single light. We just crept forward through the reeds. The old local people on the boat were true natives. This all changed too fast. It’s as if people my age have really lived through three lifetimes.

Teachers like us come in contact with a lot of young people. Some of them are a bit curious, and ask about what things were like back then. It’s hard to explain, because if you want to talk about one thing, you have to add a lot of background. If I wasn’t so loquacious, you really wouldn’t be able to understand. How did two people court each other back then? Why were their ideas so strange? That’s what the life was like then.

Xiang: I remember that Xu Bing wrote an essay about his time in a rural production brigade. The village he stayed in was very poor. One girl had only one set of clothes, and when they were dirty, she had to go naked as she washed them. Once he walked by the river, and the sun was very strong. The girl was sitting half naked under a tree, waiting for her clothes to dry. He didn’t know what to do, but she acted naturally and called out to him. I really like how he wrote it. It had sights, colors, and feelings, and it had that natural sadness that floats in the air between people, clear and vivid. My age is a bit closer. In high school in the mid-80s, we also went to the countryside, and I know what it was like in such villages. Kids these days can’t understand the background, the situation, and the emotions between people. People can’t understand a lot of the pure, minute details. Those circumstances are gone.

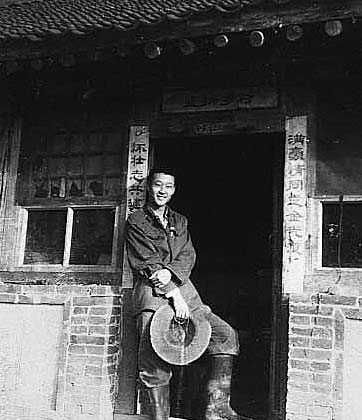

Xu Bing was at the Pots Commune in 1974, provided by Chen Feiya.

Chen: Right. When I first got to America, I hung out with the kids in the literature and English departments. I was a few years older than most of them, because I started college late. One day we were talking about a classic novel, Anna Karenina, and one of the girls didn’t understand it. She said that if two people didn’t get along, they should just separate. Why would they get so tangled up in tragedy.That left a deep impression on me. Modernization has made life so simple, so easy and relaxed. But what we don’t know is, will quite a few things never return? There are some profound things that are tied up with those bad systems. It sounds strange to say it this way, but that’s really how it is. Look at the famous works from generations ago, people’s lives, people’s spirits. But you feel that this kind of emotional state is so distant, right? Think about Tess of the d’Urbervilles. Two people fall in love, and they can’t express it. Then they come together, and each confesses their sins to each other. She says that she is not a virgin, and the husband leaves. Tess follows, for one night. The husband is great. His father is a minister, but he doesn’t want to go to college or become a minister, he wants to be a free thinker. He is the most open minded kind of man, but he feels that his dreams have been crushed. It was just a century ago, but that’s how people lived, how they thought and how they perceived the world.

Xiang: That state of affairs lasted for a very long time. The changes all took place over a very recent period of time.

To be continued...

About the author

Chen Jiaying was born in Shanghai in 1952. He entered into the Western Languages and Literature Department of Peking University in 1977, studying German, and began studying in the United States in November 1983. He received his doctorate in 1990 with his thesis Name, Meaning and Meaningfuless and then went to work in Europe. He currently teaches philosophy as a Professor at Capital Normal University in Beijing. His works include Introduction to the Philosophy of Heidegger, Philosophy of Language, The Irreducible Eidos, Philosophy Science, Common Sense, Zephyr, Beginning with Sense and Dianoesis; his translations include Philosophical Investigations, Being and Time, Linguistics in Philosophy and Sense and Sensibility among others. He is considered to be one of the most influential philosophers of the contemporary age.

Courtesy of Xiang Jing and Chen Jiajing.

The views expressed in this column are the author’s own and do not represent those of CAFA ART INFO.