Xiang Jing's Recent Creation; Photo:Zhang Yanzi/CAFA ART INFO

Part II: Mankind was like a young person, or someone in the prime of his life

Chen: As for art, I don’t know, but I’ll tell you my impression. I’ve seen a lot of artists ask this question. I say that in the past, art was always changing, but sometimes I feel like there’s a lot of commonality among all of the art before the 20th century. And then, perhaps beginning with the Cubists, the Futurists, or the Dadaists, it just suddenly changed in the early 20th century…

Xiang: The big changes started with Impressionism.

Chen: Impressionism seems to be the tipping point.

Xiang: Right. The methods suddenly changed.

Chen: There were great changes in Impressionism, but it still relied on tradition. Once Impressionism was finished, in the early 20th century, suddenly all of the new schools popped up, ones whose names I can’t remember. Before that, the schools such as Raphaelite and Pre-Raphaelite, only the experts could tell the difference between them. But now it’s different. One thing is like this, and the other is like that.

Xiang: Limitless possibilities.

Chen: Once these schools did their thing, there is not much left that one can do on-canvas any longer. Art became entirely different from what it was before. It changed completely.

Xiang: Have you been to any large exhibitions of contemporary art abroad?

Chen: I have, but not very many. When I’m abroad, I will go to see exhibitions, like when there are exhibitions while I’m in New York or Europe.

Xiang: It’s amazing to think about how fast the world has changed over the past few decades. The Internet has changed the way people perceive the world, making it easier to “know” things. Our concepts of technological progress, time and distance have all been changed. If you’re completely in the level of reality, and your attention is diverted by reality, then you will be afraid there’s something you “don’t know.” A concept is rapidly washed away, shuffled out like a playing card. The individual has been emphasized, but what has been washed away with more ferocity is the unconscious collective. Outside of advertisements, there are no longer words like “eternal” or “timeless.” For the individual, sometimes they don’t know what they want to persevere for. This world brings me great pain, and I don’t think I can use what I have now to help the future of the world. Sometimes, art seems like an utopian dream world, where each artist rushes to successfully erect a new world before the old one collapses. I’m always squeezed between such ideals and depressed sentiments. I hold a solo exhibition about once every three years, and every time, the process is the same. Before the exhibition, I shut myself off, steeping myself in a closed world. After that, I spend about a year in a state of hollow doubt, doubting all values. It’s quite scary. I wonder, does someone like you, who works in philosophy, face the same kind of doubts?

Chen: It’s probably quite different, though there are some similarities. You just mentioned the state you’re in for three years. That’s just like my normal state. You have a question, and you continuously follow that question. I also have some students and peers that I discuss things with, just a few of them. Overall, you don’t know what’s going on in the outside world. I finish writing a book, and when it is launched, and I then return to the world, I’ll find the kind of work I do is very much on the margins. When I say margins, I’m not talking about being sad because you’re on the margins of society, but because the significance of your work is marginal – you don’t know where it converges with reality. Not only do I have such feelings, I have them often.

Take Ding Fang, for instance. I don’t have a lot of contact with Ding Fang, but he is a typical case in this respect. He was an important painter in the late 80s, I’m not sure how high he was ranked, but I would consider him a hot artist in the early 90s. At the time, contemporary art was still suppressed by the Chinese government, but by then there were already important artworks. For instance, there was the “85 New Wave” and the exhibition in 89. I happened to be in China for the 89 exhibition, so I went. Contemporary art had already begun to flourish by then.

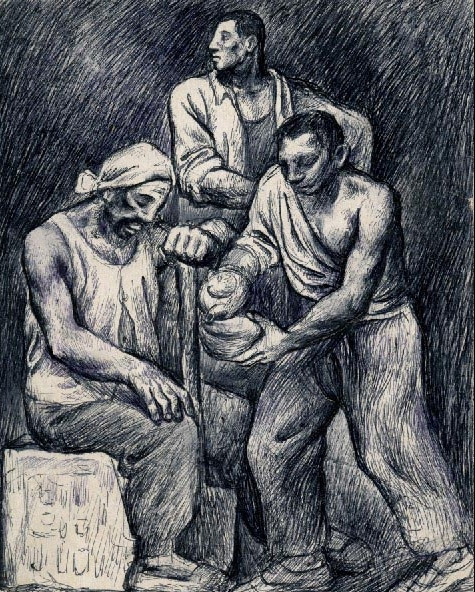

People drink water by Ding Fang

As for Ding Fang, I don’t know if it was idealism or what he was holding out for, but he stuck with it, kept painting in his old style, with his old artistic concepts. Ding Fang reads a lot of books, and is an intellectual. He is a man of letters, and doesn’t really like being seen as a painter. He is more of an intellectual. It’s been many years now, and those who support him say that he has held out, while those who don’t support him say that he is part of the past generation. I was talking with him in his studio the other day. He felt that Byzantine art, Renaissance art and his art were real art, and nothing else counted as art. Though it is shaking the world, it isn’t art. I think there’s something worthy of respect in this attitude, not being concerned with all of the noise going on outside. It is what it is. Just because it’s happening doesn’t mean it matters. But I do have a problem. It’s not that I doubt him, but I want to understand. The question of what is art is a different kind of question than the question of how far it is from the earth to the moon. There is an objective way to answer the distance between the earth and the moon question. It can be measured. No matter what you say, that is what it is. But when it comes to art, it interacts with the audience, and can you claim that all other people are wrong, taking this stuff as art, they must be wrong. But in a certain sense art needs to be accepted. I’m not saying that whoever is the most accepted is the best artist. I’m not that stupid. But there must be some kind of relationship. Am I being clear?

Xiang: Very clear.

Chen: I’d like to hear Ding Fang explain it to me more, because his views are rather extreme, and he’s read a lot of books and done a lot of thinking.

Xiang: I’ve also heard that he’s very knowledgeable about classical music, and listens to it incessantly. He likes all classical things. Perhaps it’s some kind of “classicalist fetish.” Do people have that?

Chen: A lot of people of my generation have a classicalist fetish, to varying degrees. I think you could count me among them. But, firstly, some people can accept contemporary things to varying degrees, and Ding Fang accepts them less. Secondly, most people probably lack Ding Fang’s self-confidence. For instance, with poetry, we all read ancient poetry when we were young, and a lot of us wrote in the ancient meters. Now I think the ancient meters are outdated. I write in the old meters, and I like them. It’s a personal preference. I don’t go about saying that it’s the only good thing or the only right thing, or that modern poetry is wrong or unimportant. It just happens that this is the only way I can do it. In other words, I am very accepting of the reality that classical poetry has been marginalized. I think that’s normal and proper. I don’t know about painting, and I don’t entirely feel the same way about music. When I’m with young people who write in classical meters, some of them criticize me for being weak. They say that classical poetry is good, better than modern poetry.

Xiang: I may not be all that adept at anything, but as far as I see art, whether it is what I do myself, or the music I listen to, it’s just a bunch of different forms. There is good and bad art, and then there are your own preferences. Maybe something just happens to touch you. From the perspective of art history, there is only good and bad art. There is no such thing as advancement or backwardness. If you look at art through the simple lens of “evolution,” or you pick a classic work and imitate it like the ancient Chinese, then art can basically just stop. If all you like is classical stuff, then you really don’t have anything to do anymore, because there were so many peaks. When I went to Europe, I saw the works of many of the great masters, especially from the Renaissance, like Da Vinci and Michelangelo. Though I didn’t see much of Da Vinci’s works, a lot of what I saw was experimental, and it left an extreme impression on me. When I saw Michelangelo’s David in Florence, I was close to tears.

Michelangelo's David

Next to it was a mound of marble he had worked on late in life. I feel that he completed a large part of art history, or at least sculpture history on his own. His later works could have been associated directly with the cubist school, because he had deep insight and understanding of abstract concepts such as structure and space – after all, he was an architect. For someone like that, you can imagine a young man, only 24 when he made David, a virtually perfect work of art. When you see such an artwork, you certainly get excited, but it is also hard to imagine, all of his ambition, power, strength and determination supporting him. This was a flourishing age for mankind, and such an artist made an extreme masterpiece, something that could never be surpassed. In his later years, his understanding of art was on an even higher level. Though the work was unfinished, he worked on it for a long time, and then just stopped, but his understanding, the concepts spanned beyond the classical era and linked with the modernists, even into conceptualist territory. It’s amazing! I find it really hard to imagine an artist who can span so much. At the time, mankind was like a young person or someone in the prime of his life. The self-confidence and ambition was quite moving. It was a very powerful force. It’s like when you see a very young life. You feel that it is so powerful, so full of power. Standing before him is shocking, like an electric current. You come to believe in ideas like “timelessness.” There is a profound sensibility and an intrinsic lasting value in pre-modern art. That’s why I feel that if you want to make something like that the object of your pursuits, you don’t need to do anything anymore.

Chen: Right. I think that Ding Fang would agree with what you were saying. He really has a feel for it, especially in the past few years. He has been researching Renaissance art again. He will be off to Spain and the South of France in a few days. He is obsessed with this stuff. But as for the latter stuff you said, he’s a bit different from you. He feels that the things he likes should be spread and promoted. On the other hand, he believes it is not possible for these things to be reborn and surpassed. This is not a question of individual talent, though that is essential. Perhaps you should draw nourishment from these things and then do what you can. You can even use classical methods, and even if you do, you are not repeating it. You mentioned the confidence and ambition of the people in that era. If someone were so ambitious today, you would find it laughable. That’s because in this era, we no longer perceive the world in that way.

Xiang: Why would so much ambition be laughable today?

Chen: That is a very good question. I can’t answer it, but I can talk about it, at least what my first impression is. Many years ago, a few of us were reading Wang Bo’s poem Prince Teng’s Pavilion: “Though we are old, we should be ambitious / How can we change our ambitions when our hair is gray? / As withered as we are, we should not lose our youthful ambitions.” Each word is truly a gem. I’m not talking about whether or not such a thing could be written today, but even if it could, who writes like that these days? People would think he was strange. I can appreciate it, but on the other hand, we don’t perceive the world like that anymore. In real life, that’s not how we perceive the world.

Xiang: What has actually changed here?

Chen: I don’t know. But I’ll tell you one characteristic. In ancient Greece, a city-state would have ten or twenty thousand people. At its height, Athens produced so many writers of tragedies and comedies, sculptors, painters, philosophers… all of that came out of a city-state with only tens of thousand people. The peak for Athens lasted about eighty years or so. Imagine living in a community like that. The people had an embracing view of the world, and of their own abilities. They could match talent with the rest of the world. In a sense, they could touch the world. In more physical terms, the painters all knew each other, the painters, the poets and the politicians all knew each other, they were considered the elite. Think about a city-state with ten or twenty thousand people, maybe fifty or sixty thousand at most. I often compare it to a university. Now the universities are very big, with maybe thirty or forty thousand people. The active people, the students, the young teachers, they all know each other. It’s like they live in a highly tangible world, where people’s talents and ambitions appear very real. They constantly run into very real things that will encourage or resist them.

Xiang: The world is bigger now.

About the author

Chen Jiaying was born in Shanghai in 1952. He entered into the Western Languages and Literature Department of Peking University in 1977, studying German, and began studying in the United States in November 1983. He received his doctorate in 1990 with his thesis Name, Meaning and Meaningfuless and then went to work in Europe. He currently teaches philosophy as a Professor at Capital Normal University in Beijing. His works include Introduction to the Philosophy of Heidegger, Philosophy of Language, The Irreducible Eidos, Philosophy Science, Common Sense, Zephyr, Beginning with Sense and Dianoesis; his translations include Philosophical Investigations, Being and Time, Linguistics in Philosophy and Sense and Sensibility among others. He is considered to be one of the most influential philosophers of the contemporary age.

Courtesy of Xiang Jing and Chen Jiajing.

The views expressed in this column are the author’s own and do not represent those of CAFA ART INFO.