Xiang Jing's Work

Part IV Art: Satisfying the self or saving the world?

Xiang: I agree with what you said about restraining yourself and ascertaining it within the artwork. Artwork is like an object that stands as evidence of your thinking in a certain period of time, at least for the artist as an individual. What I’ve always worried about is, aside from its significance to me, can artwork carry anything else? I’ll use myself as an example. Art is a profession where it is easy to realize your individual values and satisfy your need to express. In this era, you can gain yet more benefits, the “success” you mentioned. Sometimes you of course feel that your own artworks are good, and when you made them, you were in a very closed state, persisting for a very long time. It’s like when someone says a lot of things, and he of course hopes to be heard by others, hopes that what he abides to can be spread to others and influence others, or at least be shared. On the other hand, we always have a lot of issues with this world, thinking that this or that is bad or not good. When you create an artwork that you think is good, you are hoping that while you criticize the world, you can also produce something constructive. Through this effort, you can feel that the world won’t become too bad. When you have this “power,” you sometimes can’t distinguish between the two. Art is the best way to realize your own self-worth, but it isn’t necessarily a good way to save the world. I’m often caught between these two things. Every time I complete an exhibition, it is like depression – I feel drained for a period of time, wondering whether this thing was significant for myself or for this world. I’m cast into major doubt, my confidence has been hollowed out, and I can’t continue.

Chen: I feel that the question of “why people create” isn’t posed very well. When other people ask why I do what I do, I don’t do it for you, I don’t do it for profit, and not, in this sense, for the masses. All I can say is that I write for myself. The main issue is that the question of “why do you write” isn’t posed very well.

I recently wrote a short essay on the matter. For any spiritual activity, you can’t ask “why” or “who is it for” on any meaningful level. In the essay, some simple things like jumping in to save someone that is drowning. Why did he do it? He didn’t do it for any reason. If you must ask why he did it, then he’d say he did it to save that person. In the same way, if we ask why you made this artwork, I would guess it was to make the artwork. Why do you want to make your artwork like this? In the end, it comes down to what kind of a person you are. Back to the man who jumped into the water. Why did he jump inwhen others walked away or just stood there and watched? He’s not the same kind of person as they are. When you are already making the artwork, in a fundamental sense, you are not making it for the public or for society. To say that artworks with concrete social significance were made out of the artist’s sense of social responsibility is quite misleading. It’s just like the man who jumped into the water. He didn’t save that person just because he wants to fulfill his responsibility to society.

As to what significance your artwork has for society, I think that for the most part, it doesn’t have a lot to do with you. It’s not up to you. That’s basically what is meant when people say that artworks have their own destiny. You’re not thinking about how society should react to your artwork; you’re just doing what you want to do. You may have always cared about social issues, and this concern is connected to your artwork in another way. You’re not necessarily trying to solve some social issue with every artwork.

Though when we create artworks, we are thinking about what we should do rather than how society and the audience should react, once the artwork is complete, I believe that we all care about how society and the audience react. I don’t think that this is a contradiction. Your description just now was very realistic. You say that you make your artwork behind closed doors, and when the artwork comes into being, it marks an end to a period of certain sentiments. At this time, I listen to the audience’s reaction.

But there are many different ways to listen, and this is connected to what kind of person you are. The more internalized the listening is, the more connected it is to what kind of person you are. You’re not necessarily happy just because the social reaction is good. What’s more important is that you are not so much examining the reaction the artwork provokes, you are looking introspectively upon yourself, because you made that artwork, and you want to know whether or not it is any good. When you listen to that reaction, you don’t really care about whether the response is positive or negative; you are examining yourself through the reactions of others, trying to find out whether or not you truly succeeded in making what it is you wanted to make. When you are making it, in a certain sense you are one hundred percent confident in yourself, certain that you must do it this way to get it right. But you might actually be seeing it wrong, or fooling yourself. You thought that this is what you wanted to do, but when a weighty criticism comes, you realize that it wasn’t that there are faults with the work. When you react to these critiques, you still aren’t directly responding to the criticism, but hopefully, through this criticism, you have become more profound, richer, and you continue, as this new self, to make more artworks again. I’m not sure if that was very clear, but that is the basic process.

This is half the story. As for my understanding of the other half, you say that each exhibition is the result of a process of three years working behind closed doors. I think that there are two aspects to this experience: one is the joy of finally completing something, of putting something down; the other is a feeling of being drained. A lot of people compare it to giving birth. You could use another analogy, such as sending a child abroad. A lot of the time it is more like the latter, because you have fulfilled your responsibilities, having raised and educated the child to become an adult. Sometimes it’s not like giving birth. Once you give birth, for the mother at least, that means things have just begun. It is still in your hands, and has no power of its own. It is a part of you. But when you send your child abroad, it’s kind of like what they say about artworks having their own destiny. At this point, the mother and father have a sense of accomplishment, even of relaxation, but then there is the other aspect – it has left, it is no longer connected to me or a part of me. A child and an artwork have emptied you out and left.

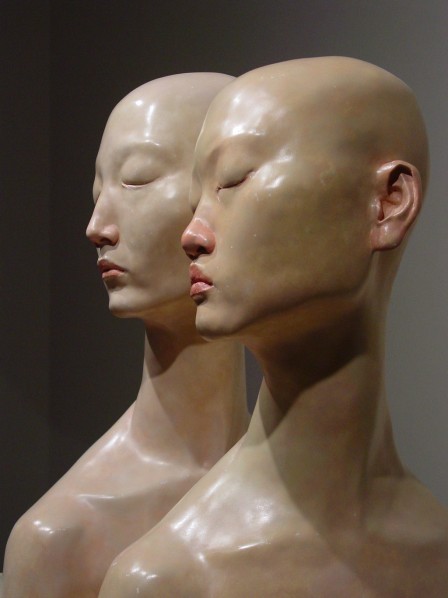

Xiang: Sometimes I really like using another analogy. When an artwork is finished, it is like a mirror. It is a mirror for me, as well as for the audience – everyone sees nothing but himself in it. I’m often startled by my works, because of this strong sense of unfamiliarity. When you’re making it, it comes from your body. All you have to do is focus on what you are thinking and feeling, and strive to transform it, letting it out through a good channel. When it is in the exhibition space, it is like you’re facing a life that you don’t know. Sometimes it startles me. Its power is something that the artist has no way of imagining. At this point, a distance grows between you and the artwork. You couldn’t imagine it, and it can’t be controlled, the feeling of the unfamiliar power of the artwork that works against you. I use the analogy of the mirror because it shows yourself, and this can be surprising.

Chen: I think that everyone has this kind of feeling towards their works to a certain extent. But your works, especially to us outsiders, appear to particularly belong to this category. People often say that your works are kind of existentialist, and there is something in that.

Xiang: I don’t know. My new works this year might be a bit different. I don’t know if I’ll have such strong feelings.

Chen: Next time we meet, I’d like to hear what you feel. This is interesting. You’re kind of like Flaubert. Flaubert has been described as the coldest of authors, and they were at least half right. I remember seeing the first caricature of him, where he was wearing a doctor’s coat and wielding a scalpel, as if he created his work by calmly doing autonomy with the scalpel. But Flaubert had another side, he is said to have said that Madame Bovary was himself. That’s quite similar to what you just said. When he wrote, it was much like creating a work of art, but when the artwork comes out, it’s something you can’t even imagine yourself.

To be continued...

About the author

Chen Jiaying was born in Shanghai in 1952. He entered into the Western Languages and Literature Department of Peking University in 1977, studying German, and began studying in the United States in November 1983. He received his doctorate in 1990 with his thesis Name, Meaning and Meaningfuless and then went to work in Europe. He currently teaches philosophy as a Professor at Capital Normal University in Beijing. His works include Introduction to the Philosophy of Heidegger, Philosophy of Language, The Irreducible Eidos, Philosophy Science, Common Sense, Zephyr, Beginning with Sense and Dianoesis; his translations include Philosophical Investigations, Being and Time, Linguistics in Philosophy and Sense and Sensibility among others. He is considered to be one of the most influential philosophers of the contemporary age.

Courtesy of Xiang Jing and Chen Jiajing.

The views expressed in this column are the author’s own and do not represent those of CAFA ART INFO.