Figure 11. Contemporary Chinese artist Liu Ye created a portrait entitled Snow Andersen (imitation of Albert Küchler's eponymous work, 1874)

by Siran Changchang

From the general principles of literary description, Andersen's depictions of the character of his Chinese roles are indeed norm-like, even though the vividness differs a lot. However, in his texts, there are not exact descriptions about the overall figure or details on the appearance of "old Chinese", Chinese emperors or other Chinese, nor spatial structural descriptions of the old living room, the Chinese palace or gardens, but in the illustrations, these elements are specific and vivid. From text to images painted specifically for it, something may be lost while others are derived.

Pictures as illustrations always have more or less attachment to the texts, however, texts of the Fairy Tales by Andersen involved with the subject "China (Chinese)"from plots to subjects, are related more to a China which existed in westerners' conception than the real one. Whether Andersen or his first few illustrators didn't come to China personally, nor study Chinese culture in depth can be surmised. All their understanding, imagination and emotions about the vocabulary "China" were built on a variety of second-hand material. What is interesting is that a considerable portion of "second-hand material" can even belong to the legacy of their cryptomnesia or the aesthetic trends.

Visual image in the text: Chinese Style as cryptomnesia

According to the "Hans Christian Andersen" written by the Danish scholar Jens Andersen, the years 1844-1845,during which time Andersen created "The Nightingale" and "Shepherdess and the Chimney Sweep", witnessed his enormous success in both life and career during his middle years. His reputation in the international arena at this time was on the crest of a wave. The long-distance travel gave him the opportunity to get acquainted with the cultural elite and aristocracy, publishers and illustrators. It is reasonable that in his successful middle age, the writer could easily be in contact with the exquisite handicrafts, luxurious items, legends and news from China. In addition, his big "Pedigree Book" has recorded Andersen's social situation. It is a scrapbook of up to half a meter high and weighing three kg which records the compliments, photographs and memorabilia of all his 40 years' travels.

Perhaps a simple look at the popular "Chinese Style" and the changing Chinese image in noble and folk life which Andersen was most likely to come into contact with would be helpful in analyzing the original source of his imagination.

As early as the late 17th century, there was an excellent "Chinese Room" in Rosenborg Castle in Copenhagen which was painted in gold lacquer upon a green ground. The images on the painted plates came from "An Embassy from the East India Company of the United Provinces to the Grand Tartar Cham, Emperor of China" by John Nieuhoff' published on 1669.The most famous recording in this book is the Porcelain Tower in Nanjing, it almost made this Glazed Tile Pagoda become the symbol of China's architecture. In Andersen's "Kingdom of Heaven Garden" of 1839, East Wind wears Chinese clothes and says: "I am from China - I danced around the porcelain tower, made all the bells ring ding-dong ding-dong"!Whether this stems from the folklore heard in Andersen's childhood or his abundant knowledge after he reached maturity, both illustrate that the second-hand image "Chinese porcelain tower" brought to Europe by merchants was widespread at that time. After being widespread for nearly two centuries, this type of recurring image carried the imaginations and understandings of several generations of Europeans so that they became the potential part of their descendants' cultural memory. Because of Andersen's lack of details, such images have stirred up his beautiful fantasy which is also reflected in his understanding of China and Chinese culture.

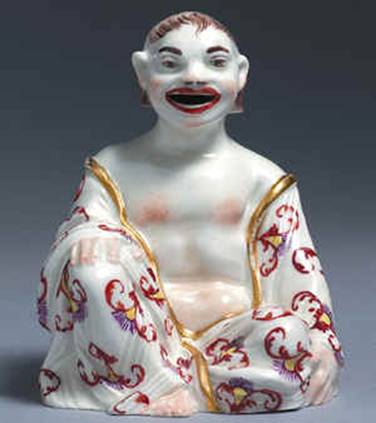

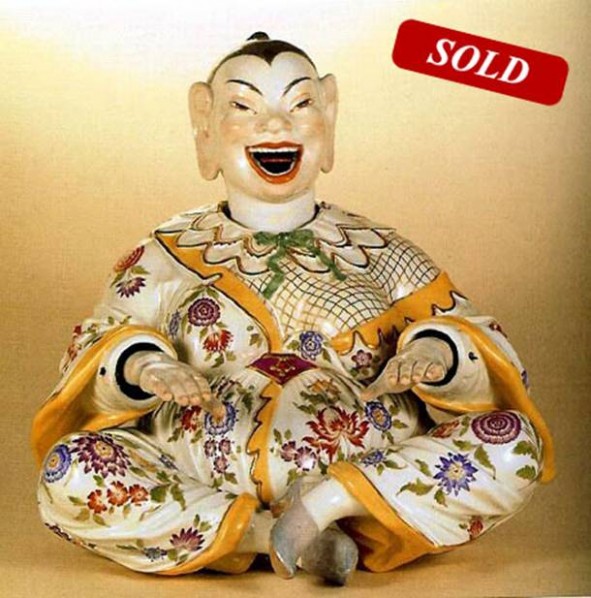

Figure 1. German Meissen porcelain factory designed and produced a series of Chinese human sculptures, among which Pagoda--deformation of the Cloth Bag Monk, 1725

In the 18th century, ceramics factories around Europe produced a large number of ceramic figurines, familiar with "Shepherdess and the Chimney Sweep" and "Old Chinese" these figurines tend to use legendary figures, they are bright-colored and the C-shape and S-shape are wildly used. The then German Meissen porcelain factory designed and produced a series of Chinese human sculptures, among which Pagoda--deformation of the Cloth Bag Monk- was the prominent representative (Figure 1, Figure 2).This image was once popular in the Rococo period in Europe during which the Chinese style was flourishing, so it could also be understood as Europe’s second-hand imagination about the Chinese and their rich life. Perhaps, Andersen's imagination about a Chinese emperor and the court life was related to the cryptomnesia constituted by these figurines.

Figure 2. German Meissen porcelain factory designed and produced a series of Chinese human sculptures, among which Pagoda--deformation of the Cloth Bag Monk, 18th century

But in the 19th century, Europe forcefully gained more and more trading privileges in China, the image of China and the Chinese people plummeted in Europe. In the 1860s, even Voltaire began to say: "Those so praised things now appear to be such unworthy people should end their excessive prejudice about this nation's wisdom and sageness ". The historical reasons for this kind of change will not be discussed in this article, the key point is the visible fact that until the mid-19th century, the image of Chinese people in Europe formed a new hybrid concept: first, ignorant and repressive; Second, money worship and evil; Third, Strange and sophisticated.

These features were Europe's general impression about the Chinese when Andersen created the image of "Old Chinese. Unfortunately, I could not find information about the European-produced decorative porcelain figurines in the mid-19th century, as for the lifelike image of a "porcelain grandfather" this appeared frequently in illustrators' works of the 20th century, there are only two possible reasons: first, they are all based on Andersen's description and combined with the imagination of the Chinese in that era of the "Yellow Peril" flood ; Second, around mid-nineteenth century, there appeared such porcelain figurines, or until the mid-nineteenth century, European households still displayed such small crafts which have been handed down from the era of the Chinese style. In the view of the image (rather than written records) this played a powerful role in people's way of thinking and feeling and memory, I tend to agree with the latter conjecture.

Visual Images in Illustrations: form ,taste and free interpretation

Figure 3. Vilhelm Pedersen (1820-1859), Shepherdess and Chinmney Sweep, 1849

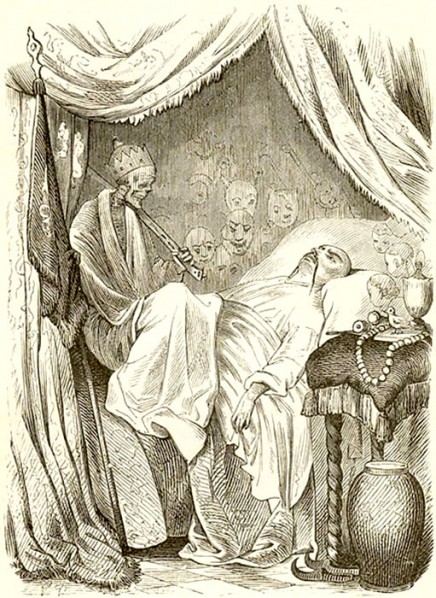

Thomas Vilhelm Pedersen, (1820-1859) was the first one to draw illustrations for Andersen Fairy Tales. In 1849, the five-volume illustrated Andersen Fairy Tales was first published, Pedersen drew a total of 125 woodblock prints. Because the five-volume illustrated Andersen Fairy Tales selects a lot of passages, each story has only one or two illustrations, so what scenes did Pedersen choose is very interesting. In the only illustration he made for "Shepherdess and the Chimney Sweeper" (Figure 3), there is no image for the old Chinese man. In the illustration for the "Nightingale" (Figure 4), the dying Emperor of China is portrayed as a man of Qing Dynasty with a goatee and long braids who stretches a thin, weak woman-like hand out of the sheet. I would like to speculate boldly if Pedersen's illustration can represent the understanding of the academic art in the mid-nineteenth which was too mature to be on decline of China and Chinese to a certain extent? This country is always a distant presence full of exoticism, people there are incomprehensible, horrible and disgusting, but still have a strong attraction.

Figure 4.Vilhelm Pedersen, Nattergal, 1849

In the 1860s, new factors like Japanese prints have entered into the Impressionists' innovative tests. In the early 20th century, the field of industrial arts or so-called Art Design underwent a major change. Starting from the Aestheticism and Symbolism in the late 19th century, a slim, sick and weak style gradually rose in the field of graphic design. With the rise of Art Nouveau, a sentimental nostalgic but somewhat befuddled new taste dominated the design field of Europe and the United States, in the early 20th century, of course, illustration was of no exception.

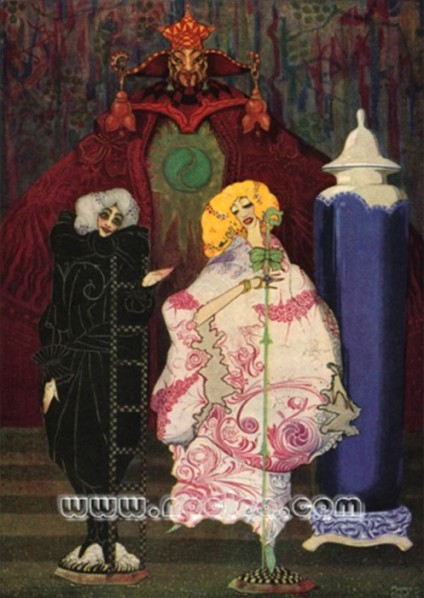

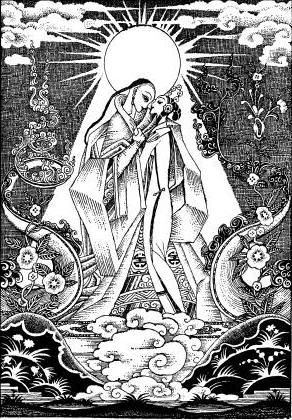

Harry Clarke (1889-1931) was the leader of the Art Nouveau movement in Ireland. The "Andersen Fairy Tales" illustrated by him was published on 1916 which included 16 colorized plates and more than 24 black-and-white plates. It was then the so-called "Golden age of gift books", Clarke's style is complicated with extremely complex decorations, bright and rich colors and full of oriental exoticism which give prominence to a plain and decorative sense .

The Old Chinese as the background of the shepherdess and the chimney sweep looks as if a pattern was printed directly on the wallpaper in addition to his official cornered hat of the Qing Dynasty, goatee and yellow face. It is difficult to see what a "Chinese" heart hidden in the extremely exaggerated deformed crimson robe was like. Even the young man and woman in the foreground are two dolls embedded in the external clothing delineated by a bunch of beautiful curves (Figure 5). He doesn't care about what exactly Andersen wrote -what is important is no longer the meaning of the text but the visual effect which is precisely the spirit of the Art Nouveau.

Figure 5. Harry Clarke (1889–1931), Shepherdess and Chinmney Sweep, 1916

The Art Deco movement in the 1920s and 1930s was opposed to the one-side stress on the craft, gothic and natural style of the Art Nouveau, it proposed to learn from traditional art and design, to advocate Machine Aesthetic and laconic geometric shape designs. At this point, illustrations of the gift books continued to pursue beauty, but more slender and a softer style occurred, it was the Danish artist Kay Nielsen's(1886-1957)illustrations for Andersen Fairy Tales .

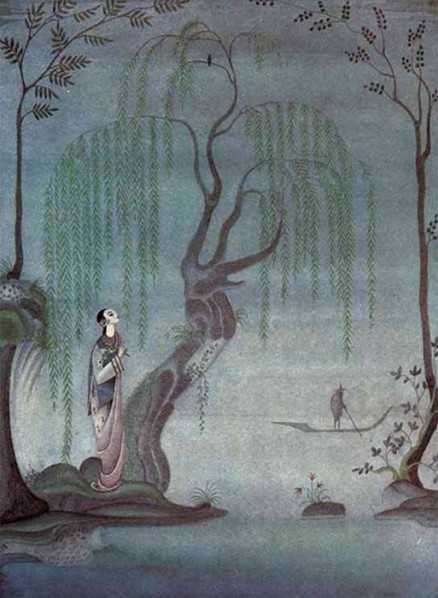

Figure 7. Kay Nielsen (1886-1957), Nattergal, 1924

His illustrations have a strong personal style and are a strange mixture of both large white space, exaggeration and distortion, gorgeous colors from Japanese Print and elements from Aubrey Beardsley. The obvious difference between Nielsen and his predecessors is that he abandoned the image of the Chinese emperor in favor of depicting a quiet picture of a Chinese village with delicate lines and colors (Figure 7). This is not the key plot in Andersen's text. It can be seen that artists in this period paid more attention to the harmony and beauty of illustration itself than its attachment to text. It is noteworthy that the shepherdess he drew(Figure 8) is clearly a European girl whose modeling is basically constituted by two circles of one large and one small. Besides, in his illustrations of 1930 created for Romer Wilson "Red magic: a collection of the world's best fairy tales ",the Chinese girl is still modeled with a long oval shape (Figure 9), which means not only that the Chinese girl wears a large robe, but also she is firmly fixed in this dress: She cannot pick up her skirt, lift her legs to climb out the chimney like a shepherdess in Europe, she could only stand quietly.

Figure 8. Kay Nielsen's Shepherdess and Chinmney Sweep, 1924

Figure 9 .Kay Nielsen's illustration for Red Magic a collection of the world's best fairy tales, 1930

Is second-hand material the best source of imagination?

In one letter Andersen wrote to his best friend Mrs. Dorothy Mel Cheer on July 21, 1867, he said: "Paper-cut is the beginning of the creation of poetry." Andersen used to tell stories for children with improvised paper-cuts, he often cut an "Oriental Palace" (Figure 10). In fact, this palace is completely Andersen's self-creation which blends all kinds of styles from the Near East to the Far East. In his Oriental palace, the most closely related to Chinese elements are the curling eaves and the hanging bells. It seems that the Chinese porcelain tower is indeed one of Andersen's magical imaginations which is indeed very cute, but it can only be produced in second-hand material mixed with distortion, oblivious and freewill additions.

Figure 10. Andersen's improvised paper-cut, Oriental Palace

2005 was the 200th anniversary of Hans Christian Andersen's birthday, the contemporary Chinese artist Liu Ye created a portrait entitled "Snow Andersen (imitation of Albert Küchler's eponymous work, 1874, Figure 11)" (now in the possession of the Sperone Westwater Gallery in New York, Figure 12). There are two kinds of second-hand material: First, the Chinese translation of Andersen Fairy Tales: second, the presswork of Andersen's portrait made by Albert Küchler (1803-1886).

Figure 11. Contemporary Chinese artist Liu Ye created a portrait entitled Snow Andersen (imitation of Albert Küchler's eponymous work, 1874)

Figure 12. It is now in the possession of the Sperone Westwater Gallery in New York

Is second-hand materiel an ideal source of imagination? It can provide a wonderful confusion of space and time, experience and adequate space for misunderstanding, perhaps there are some irreplaceable artistic imaginations that can only arise from this foundation.

The views expressed in this column are the author’s own and do not represent those of CAFA ART INFO.

About the Author

Ms. Siran Changchang, Master of Arts on Cross-Cultural Art Studies at Central Academy of Fine Arts (Sep. 2008 to Jul. 2012)

Cell: 0086-13701175871, Tel: 0086-25-83562731 E-mail: shirangchanchan@hotmail.com

PUBLICATION

Siran Changchang, “Between Images and Texts: Second-handed Material and Imaginary China”, Art Observation ( National Core Periodical ), July 2009, p121-125

Siran Changchang, “The History Returns to Painting Through Photography”, Oriental Art – Master, vol. 207, June 2010, p124-129

Siran Changchang, “Escaping Into Life: Analyzing the significance of images in Chen Wenji’s Oil Paintings of the early 1990s”, Chen Wenji’s Retrospective Album, 2010

Translated by Siran Changchang, “We Are the Landscape: A Conversation with Steven Siegel by John K. Grande”, World Art ( National Core Periodical ), 2010/3, p29-32,

Translated by Siran Changchang, “Cui Guotai: Rust Never Sleeps”, by Patricia Eichenbaum Karetzky,Oriental Art – Master, vol. 187, August 2009, p145-153

EXPERIENCE

Temporary Assistant Editor: Department of Academic Studies, National Art Museum of China, May 2008

Temporary Gallery Assistant: Universal Studios Beijing (now renamed as Boers-li Gallery), April–May 2006

Reporter & Editor: Hong Art Magazine, Beijing, February—April 2008

Translator of English Papers & Reports for Magazines: Art Value, Oriental Art, Vision Magazine, Contemporary Art, etc. 2007-2010