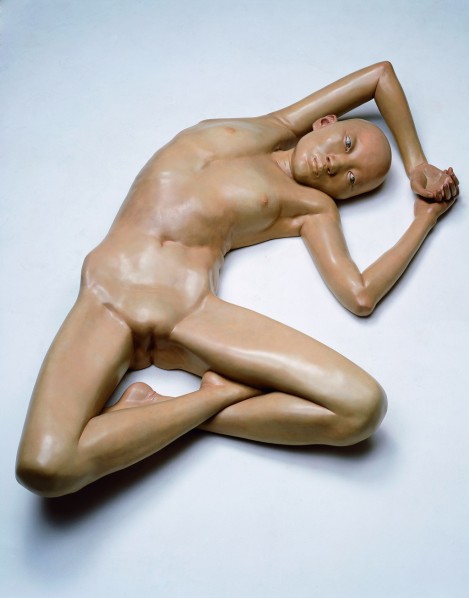

Xiang Jing, I Am 22 Years Old, But without My Period, 2007; Fibre glass, painted, 30x155x95cm

Part V: We are all common people now

Chen: You spoke of the feeling of being elite. Can you talk more about that?

Xiang: When I was young, that elite feeling was rather strong, perhaps owing to the environment of the time. I was eager to be an elite person, strove to reach the highest level in the hope of becoming one of “the few.” But it seems that somewhere along the way, I forgot this concept. I don’t know why, whether it’s some democratic ideal or something else that influenced me, but I grew disdainful of this elitist notion. I started to change, to think about a society where all people are equal. Especially in my early days of doing art, there was a long time that I actually felt puzzled by and even had a bit of disdain for contemporary art, or at least the kind that was obscure or difficult to understand. At the time, I was trying to make something that in theory everyone could understand or perceive. What I mean is that I really wanted to restore the perceptibility of art. This was a product of art being controlled by the massive interpretive system. Art appeared more diverse, with more possibilities, but because art was becoming more difficult to understand, it came to belong to a small circle. That is what I felt disdain for. I think that art does not necessarily need to be explained, or it doesn’t need to rely on interpretation for its existence. “Theoretically” speaking, it triggered another channel for people. It can be perceived, and what it reflects is the world in which we live and exist ourselves. For a long time, I was trying to do things under this notion, trying to reflect a component of human nature. I expected everyone to understand it. Perhaps it was because I had wanted to do this for such a long time that it led me to forget my earlier notions of “elitism.”

Of course, now I am quite confused between the two, including what I wrote about in my letter to you. When I see the poverty and inequality in society, the widening gaps between people, even though it appears the world has become flat, and a lot of things can be shared, in fact, this inequality is growing ever more drastic, and power is growing increasingly concentrated. A lot of things appear to be growing increasingly contradictory. It is at these times that I begin to have doubts about what I am doing behind my closed doors. Whether it is my art or my deeds, I wonder about how to deal with my position as a part of society. If you have this notion of elitism, then you have to take something on, and I get a feeling that there are many things that have more significance to social change than art.

Chen: I want to reply to two of your points. First of all, judging oneself according to elite standards is of course something you do when you’re young, when you do things later, you wouldn’t always think about what elite is and what isn’t. Instead, you merely think about how to do things well.

The second point is your concern for social issues. I talk about these things with friends and acquaintances a lot. Some of them take part in social movements, civil rights activities and related work. A friend of mine in Shanghai is in the field of psychotherapy. She often encounters very sad things, and cares about these things, stuff like the suicides at Foxconn. There are also lawyers and policemen in similar situations. They encounter that side of society more.

Xiang: Doctors, too. That is quite negative.

Chen: I think that artists and philosophers can see less of that in their professional lives, but you also have to take a deeper look at the issues modern people cannot hide from. The question is, can I still approach social problems with an elitist mentality today? In the past, even when helping out the disadvantaged, I could do it with an elitist mentality.

Xiang: There are psychological advantages to the world-redemption approach.

Chen: Right. When we perceive these things today, we are not perceiving them from the elitist perspective. We feel that everyone, in a fundamental sense, is a common person. In this sense, elitism has really reached the end of the road. I think that since ancient times, the person most keenly aware of this was Nietzsche. A lot of people ask about the political significance of Nietzsche, and I don’t know, but to a great extent, I think that Nietzsche was not answering this question. Instead, he was answering another question – the question of how elite people could or should handle things in modern society – if they still exist at all. I think that this elitism is a great entry point to a number of issues.

Xiang: I used to make the simple supposition that throughout history and even in this era, things must have been led along by a minority of people. I still believe that. In this day and age, it may still be the case, but it’s not the same concept anymore. There was a period where I was very interested in political ideas, and I discovered that a lot of relationships are in essence about power. As long as it has something to do with influencing events, then it is connected to power. Even in the realm of art. Once you leave the scene of creation, you immediately enter into a power structure. A lot of artists even have strategies about power relationships when they are creating their art. Nowadays, it is no longer about good, better and best, but about balancing and breaking away from power. Of course, that’s another topic.

Chen: We are all modern people. When we talk about ethics, the Greeks had a word called “arete,” which we would translate as virtue or morals. We used to translate it as morality, but after the “linguistic turn”, people didn’t really say that anymore, because people discovered that there are actually a lot of differences between arete and virtue or morality. Now, we tend to translate it as “excellence.” For instance, in the conceptual system of Homer’s epics, we don’t say “morality,” we say “excellence.”

Xiang: Excellence?

Chen: When someone has military prowess, they would use the term "arete", and the context doesn’t really fit if you translate it as “morality.” Courage is a kind of arete. Today we see courage as a virtue, but for Homer, this was quite removed from what we now call “morality,” and closer to things like agility and military prowess. It’s saying that he is outstanding, very smart, very courageous, with martial prowess and political wisdom. This is what the Greeks would call "arete". There have of course been a lot of changes in western conceptions of morality over the past two thousand years, for example, the morality of Christianity, and this came into conflict with the concept of arete. But in the West, the shadows of arete are still there. “Excellence” is still there. For instance, we were talking about the people of the Renaissance. They were different from us in a lot of ways. Simply put, they would pursue excellence above all else. Outstanding people viewed the pursuit of excellence as natural.

Xiang: From this perspective, it becomes much easier to understand the pursuits of the people during the Renaissance and the entire classical era.

Chen: Elite people are simply those who pursue excellence. For instance, in late 19th century Vienna, we saw a whole group of people pursuing excellence. If you read their biographies, you’ll feel that they’re much more than just a century removed from our own time. The mentality of the people then was just so different from our own. I could count off a long list of people, like the musician Johannes Brahms, the poet and novelist Stefan Zweig, the economists and as well as Wittgenstein, the thinker that I’m most familiar with. Vienna at the time was like another Paris. You can see a whole group of elite people pursuing “excellence.” Whether you made music, painted, studied philosophy or other things, you had to do it very well. As long as you did it excellently, then it had meaning. It was like one last flash of the classical era before total modernization, one last such era. For them, strict requirements of the self were not based on the kind of morality we have. Of course excellent people asked a lot of themselves. What about today? There seems to be sufficient reason behind any way one does things – the pursuit of excellence is one way of life, and being able just to get by is another. Excellence has been brought down to the flat world where it is merely one way of life among others, and so there is no such thing as so called excellence.

After the two world wars, these things seemed to suddenly become outdated. When we ask about their significance now, it seems as if we’re asking about the significance to the people at large. In the past when we spoke of excellence, it didn’t really have much to do with the toiling masses. As Aristotle said, it is the so-called potential of man. It was a person’s abilities in art, ideas or the spirit. It was seen as something entirely positive.

I wonder if the concept of the elite can be mostly understood from this perspective – that he finds a medium that allows him to develop his potential to the fullest. Once it is developed to the fullest, it becomes, in a certain sense, a work of art. It’s like mankind coming together to create a Pantheon. If we look at all the splendid artworks that we place in this Pantheon, whether it is music, sculpture or something else, these are in the end the highest goals of mankind, not something else. I think that this is an idea with a long tradition behind it, a very vibrant idea, but I think it rapidly declined after the two world wars.

Xiang: What replaced it?

Chen: I don’t know what has replaced it, but what constantly comes up today is the idea that most people, perhaps all people, should live lives not maimed by poverty and political terror. This seems to have turned into something everyone must be concerned with. A writer can no longer be like Proust, writing his À la recherche du temps perdu in the midst of a world war. If you go take a walk at the Summer Palace, the speakers are all announcing that “These pillars and carvings were all erected by the sweat and blood of the working people.” When I hear that, I think, it’s true. It’s really a dilemma. The pyramids, the pantheon, they were all built with human blood, sweat and tears.

Xiang: I often think about this. The blood and sweat of the people is still there, but why are they no longer creating miracles of human civilization?

Chen: Before, it seems that our goals faced upwards, looking to see whose works were closer to god, closer to the divine. That was the goal of mankind. Now it seems things are reversed, where we see the lowest level as the standard for judging what is proper. As for us, people with meaning like you and me, we can’t avoid feeling conflict between the two.

Xiang: So you do face this perplexity as well…

Chen: So we lack the confidence of our predecessors, who only cared to pursue excellence.

Xiang: That rapid speed is gone, too. Progress has slowed down.

Chen: Ding Fang is always talking about the paintings and sculptures of the Renaissance, that internal confidence that the people expressed – he uses the term “confidence,” a word he really likes to use. He links that internal confidence with faith. He is very fixated on religious faith. In today’s context, I would say that this confidence belongs to the elite. It’s an upward-looking vision. In the 80s, there really wasn’t a concept of the successful person. Back then, the concept was of the elite. Now, the concept of the successful person appears to be widespread, a “mainstream” idea among the youth of this era. In the early 80s, you wanted to get into the Central Academy of Fine Arts, or Peking University, the natural idea is to be one of the elite. Nowadays, if you are tested for Tsinghua or Peking University, the idea is to become a successful person.

Elite people are responsible to a higher power, which is called God or Heaven. Even if he wants to change the world, to make an achievement he must face something higher, something beyond earth. In that sense, it’s not actually all that important whether or not he actually changes the world. Changing the world is just the path of the elite. Even if it’s someone like Anthony, running out to the desert to meditate, that’s also a kind of elite. In other words, one’s impact on the world comes second. Today, I will use business, politics or even art to change the world. Roughly speaking, there are two levels of meaning behind changing the world. In one sense it is the old sense, which is to cast the world in a new light, through which the world is changed. Another kind is to actually change the world, by perhaps making it richer or less filled with pestilence. I think that today’s outstanding people are more interested in actually changing the world.

Xiang: That is perhaps because they have less connection up top, and more channels for connecting with the bottom.

To be continued…

About the author

Chen Jiaying was born in Shanghai in 1952. He entered into the Western Languages and Literature Department of Peking University in 1977, studying German, and began studying in the United States in November 1983. He received his doctorate in 1990 with his thesis Name, Meaning and Meaningfuless and then went to work in Europe. He currently teaches philosophy as a Professor at Capital Normal University in Beijing. His works include Introduction to the Philosophy of Heidegger, Philosophy of Language, The Irreducible Eidos, Philosophy Science, Common Sense, Zephyr, Beginning with Sense and Dianoesis; his translations include Philosophical Investigations, Being and Time, Linguistics in Philosophy and Sense and Sensibility among others. He is considered to be one of the most influential philosophers of the contemporary age.

Courtesy of Xiang Jing and Chen Jiajing.

The views expressed in this column are the author’s own and do not represent those of CAFA ART INFO.