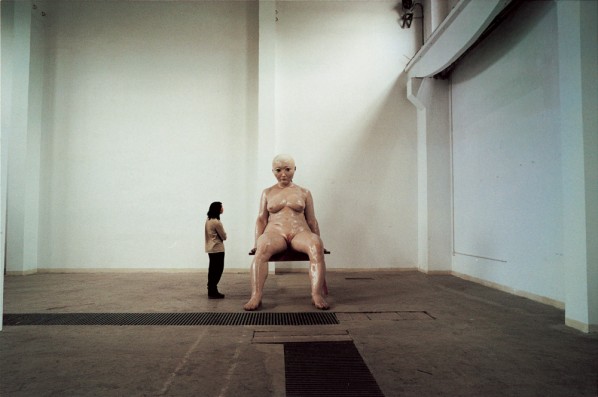

Xiang Jing’s “Bang!” (2002), in painted fiberglass

Part VI: We are producers

Chen: A young friend suggested that Life magazine interview me. I don’t remember the title of the article, but it was basically about seclusion and refinement. I said that the topic didn’t suit me, because I had never lived the refined life, nor had I seen it. During the interview, I said that we all engage in the production of a refined person. It’s a bit connected to what we were just talking about. I said that Beethoven was not a refined person – we all know this – but the people who listen to Beethoven are.

Xiang: We all belong to the productive force. A lot of people have this misconception, mixing the life of the artist together with art, linking the worker with the work itself. The producer is actually a laborer.

Chen: Right. I’m not just saying this, I really know it. Sometimes I take part in some “social engagements.” Someone has read your work, and sees you as a refined person, a social person. But you know that you’re not. You write, and bury your head in your work.

Xiang: There’s no appeal.

Chen: Right. You just mentioned laborers and producers. Actually, once a producer enters the refined circle, his productivity drops markedly. If he gets used to such circles, then he is basically no longer useful as a producer.

Xiang: I think this is very apparent in the art scene. Artists can enter the level of successful people in a very short amount of time, and most people, if they lack the determination, basically immediately turn into “refined” people.

Chen: Yes. I haven’t experienced this, but I have seen it.

Xiang: So sometimes I think what supports you and makes you carry on is a view of values. If you see so-called success as a ladder that leads you to a higher society step by step – turn this into your values – then perhaps creation itself becomes insignificant. What counts is your values, and your creative work is to support and affirm these values, and you begin to see all the other trappings as distractions that won’t bring you much joy.

Chen: Right. This is connected to a lot of social situations. In 18th century Europe, the social scene was basically the aristocratic circle, but it was closely connected to the laborers of art and ideas. It had high standards. As a result, the influence of this social scene wasn’t very negative. Goethe, for example, straddled both worlds. He was part of the social scene, but on the other hand, he was always a producer, and he maintained his productivity well.

Xiang: Goethe was perfect.

Chen: Of course, it depends on the person. Beethoven was never suited for that kind of circle. He didn’t have that kind of spirit.

Xiang: There is a certain type of artist that can never get in.

Chen: This is especially the case these days. Spiritual laborers are even further out on the margins. That is why I understand Ah-Jian’s sentiment that once you enter the circle of successful people, you’re basically finished. The spiritual standards of today’s successful people are just too low. This is especially the case with China, which lacks a group of successful people with high cultural standards. The cultural traditions are in tatters, and people must grab success with their hands, rather than accumulating it over generations.

Xiang: I don’t really interact with a lot of young people, but you do. Are there a lot of people willing to engage in academic thinking on issues?

Chen: “The forest is large, and there are all kinds of birds.”

That phrase was used for criticizing things, but now I use it in a positive way. Since I've taught philosophy, a lot of people asked me if there are young people willing to listen to this stuff. That is my answer. With China as big as it is, even if the oddballs make up only a small portion, they are still great in number. However, there are two issues. For one, having only the willingness of doing it is not enough, you have show great ability in it too. We all know that young people are idealists, but their power isn’t sufficient to take them very far. The overall situation in society is that some fields are seen as having a brighter future, such as IT or finance, and if a child has exceptional talent, he will be lead towards these fields at a young age. I actually pity them if their natural talents allow them to do thinking and art well.

There’s something else, which you mentioned, and I think the pressure is greater for them in this regard, which is social concern. You provide a young person with a good route for making money, and he doesn’t take it, insisting on following a path like that of art or philosophy. He would often be a relatively sentimental and susceptible type of person, and in this social situation, he is prone to be more sensitive to social inequality, stratification and the growth of power. This perception is perplexing for us, but we still seem to be able to close our eyes and get back to work. But when you don’t have a job to go back to, whether it is art or philosophy, when you’re just becoming interested in it and don’t have anything concrete to do, it can be very disconcerting. When we were young, no matter what we were doing, we thought it was the best, and now we have started doing it. Even though we are so absorbed in our work, we often doubt ourselves. Their doubt may be more profound. They have just begun, and they wonder, is this right, is that good, should I be doing this? That makes it very difficult to do things well. And these are things that desensitized young people can’t do.

Xiang: It’s quite a dilemma.

Chen: Yes, it is. Just in our little field of philosophy, which is very, very small right now, some people are just doing technical things, and they do them very well, earning high degrees, studying abroad and coming home to serve as professors. They do their thing well, and some of their work is needed academically, but if it’s not related to spiritual concerns and spiritual power, I don’t think it’s very meaningful. People like Chen Yinque and Zhang Taiyan had a vast and powerful concern for the spirit, even though they didn’t talk about it all day. They did academic work, and did it well, but they couldn’t just care about the real world.

Xiang Jing, Infinite Polar, 2009; Bronze, 700 x 220 x 220 cm, Collection World Expo

Part VII: The carrier of China’s cultural destiny

Xiang: Mr. Chen, I would like to interject here with a question, because it is something I’ve never been able to understand. Chen Yinque used his last years, I’m not sure how many of them, to write An Alternative Biography of Liu Rushi. I wonder how you view such a seminal academic spending so much time writing about such a person?

Chen: One view is that this was a bit of a joke on his part, but I don’t really accept that. I have a friend named Wang Yan. He is quite a figure. He was the executive chief editor of Du Shu magazine in the 1980s, when it was a highly influential magazine. He came from an illustrious family and had an encyclopedic knowledge. He knew all of China’s cultural figures. He spent a lot of time researching Chen Yinque, and wrote a book, but never finished it. I often criticize him for being too lazy and carefree. He’s really great, but he’s not a laborer. The book should have been finished long ago. I’m not sure what he’s caught up on. Nevertheless, his view on this matter is the one I find the most credible. He believes that Chen Yinque looked through the changes in China over several thousand years with one main goal in mind, which was to see if there was still hope for this great civilization of China, or to see who would carry the destiny of the Chinese civilization. He loved this civilization dearly with all his heart, and tried to comprehend fully how the lineage had been handed down and how the heirs were chosen one generation after another. By gaining a full understanding of how it has been inherited, there was a possibility of foreseeing whether the civilization could be passed on in the future. He researched the politics of the Sui and Tang dynasties. He said that a monolithic ethnic culture was sure to decline, so it needed to fuse with other ethnic groups, to bring in fresh blood. That is why he was interested in the Sui and Tang dynasties. His research of things like the Li family line was no coincidence. He felt that the Sui and Tang dynasties represented a renaissance in Chinese civilization attained through fusion with other cultures. During the Sui and Tang, the Han Chinese intermingled with the Tibetan and Northwestern people. He researched the culture of Dunhuang, because it most clearly embodied the fusion of Han civilization with outside cultural elements such as Buddhism, as well as the onslaught of new ideas and its responses. As Wang Yan sees it, Chen Yinque, through his understanding of the changes taking place during the Ming and Qing dynasty, came to understand that the carrier of Chinese culture’s fate wasn’t the literati, but people like Liu Rushi. First, she was a woman, someone on the margins of society. She was not from the upper rungs, but she was very culturally sophisticated. They were not mainstream literati or men of letters, but they had a very accurate understanding of the substance of our culture. It was people like this who carried on the thread of Chinese civilization. That was the basic idea. That is why he was interested in a person such as Liu Rushi. He used this massive book to research her life story and her social environment. Of course, it was a purely historical approach – stories, but no commentary. I have read An Alternative Biography of Liu Rushi. I don’t have such a strong foundation in Chinese culture and classical language as Wang Yan, but when he told me this, I felt that it was an accurate interpretation. Even if you don’t understand it on such a deep level, when you read it, you will see how much Chen Yinque admired Liu Rushi. There is a wealth of information about her. It goes beyond the culture we usually discuss – she has a soul, and it is intertwined with that culture. When it comes to culture, when it is too refined, when it is too cultured, it loses its soul. When it loses that flesh and blood, that soul, then culture begins to go adrift. Flesh, blood and the soul are the real culture. For culture to be passed on, it cannot be too high or too low. It must have a body and a soul.

Xiang: When I heard you say that the carrier of destiny was a woman, I was astonished. I find it unimaginable that within Chinese culture and traditions such a notion could be accepted.

Chen: At least, that’s what Wang Yan said.

Xiang: It struck me as very fresh. All of what you said, including the idea of the “soul”; these are terms that are probably rarely heard when it comes to Chinese culture.

Chen: Perhaps we can use the word “heart” as well. Culture must seep into the heart. It’s not just about cultivated manners. It must be in the heart…

Xiang: And it reflects the heart.

Chen: Yes, the one that can reflect the heart. Only this kind of culture can be passed on, rather than just being carried on superficially to eventually become some kind of tourist culture. True carriage of culture is not static. Culture must change, because hearts and minds change. That change is real, substantial change, rather than just trends or fashions. It’s not about passing on traditions no matter what they are. You draw from what you perceive inside, rather than just copying it for the next generation. When you face the world in front of you, you draw power and meaning from within a tradition.

Xiang: It's exactly the issue that lots of artists are currently thinking about.

Chen: As for women, we have seen so many outstanding women in every field. If women weren’t held back so much, who knows how many would have been able to make great achievements. On the other hand, I think that women are more easily lured in by this consumer society. Sometimes it’s as if this consumer society was developed for women.

Xiang: I think this logic should be turned around, because women were first an object of consumption. In order to shape this object of consumption, a world of consumption was created, teaching women to take on a dazzling appearance and be consumed.

Chen: You’re certainly right.

Xiang: Let’s not talk about women’s topics today as I’m afraid to talk about it. I was just astonished to hear you say that Liu Rushi was the carrier of the culture’s destiny. I’ve never thought about it like that before. I’ve never been able to understand why Chen Yinque wrote such a biography or what he meant to accomplish with it. As to its connection with cultural carriage and the heart, I certainly accept that.

Chen: Yes. This is certainly a fundamental question. As for me, sometimes I hate the way I am, always at great pains to think about little things. I wish I could escape from this status.

Xiang Jing. Your Body. 2005. Colour paint on reinforced fibreglass

Xiang: But I think you’re pondering the big problems, the big issues. Sometimes I feel that art is a little thing. Sometimes I feel hopeless, that I’ve used a lifetime to do something real small, tiny, like a speck of dust.

Chen: Labor is good. All I worry about is after a long time, whether or not it will be like a production line. I tell my students, when you listen to my lectures or read my writings, if you discover that I’m repeating myself or looking at various problems through the same lens, if you’re a good student, you should tell me even feel sorry about this. You gradually turn into that and you don’t know it yourself. When I was young, some of my old professors were like that. I thought at the time, if I live long enough to become an old professor like that, it would be a tragedy.

July, 2011

The End

About the author

Chen Jiaying was born in Shanghai in 1952. He entered into the Western Languages and Literature Department of Peking University in 1977, studying German, and began studying in the United States in November 1983. He received his doctorate in 1990 with his thesis Name, Meaning and Meaningfuless and then went to work in Europe. He currently teaches philosophy as a Professor at Capital Normal University in Beijing. His works include Introduction to the Philosophy of Heidegger, Philosophy of Language, The Irreducible Eidos, Philosophy Science, Common Sense, Zephyr, Beginning with Sense and Dianoesis; his translations include Philosophical Investigations, Being and Time, Linguistics in Philosophy and Sense and Sensibility among others. He is considered to be one of the most influential philosophers of the contemporary age.

Courtesy of Xiang Jing and Chen Jiajing.

The views expressed in this column are the author’s own and do not represent those of CAFA ART INFO.