YANG Xiaoyan

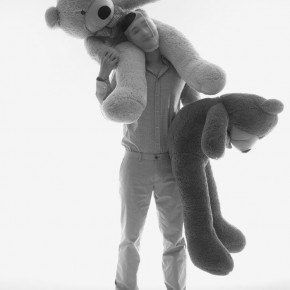

Chen Xi has summed up her decade-old pursuit of art in three words: “Flight of Freedom”, a name chosen by the artist for her painting collection which is soon to be published. This designation reveals how as a woman artist, she understands her own artistic endeavours with two associated yet conflicting goals, i.e. freedom and flight.

Freedom is essential within nature, like an habit, for all artists. The pursuit of freedom is perfectly legitimate, especially in the realm of art. A hundred years ago, Sigmund Freud declared that a dream is a disguised fulfilment of a repressed wish. Soon, this Austrian neurologist, who was obsessed with hypnotism in early days of his career, concluded that art is actually a dream in the real world. This conclusion was backed by evidence, which he had found out by surprise, that art has all the hallmarks of a dream. Art is a daydream, a materialized dream and a dream in a realistic form. The disguise repressed a wish that takes place in a dream and becomes the form of aesthetic appeal. The repressed wish in a dream becomes an art motif, and the meaning of a dream constitutes the emotions and essence of art. It turned out that this miraculous neurologist extended his research to the realm of art, in the hope of finding answers to problems that had eluded him in the realm of a dream.

Over a century has passed, almost no one today take Freud’s propositions on art seriously, but it does not matter that his views are outdated. It is true that we already have a more elaborate interpretation of art, but it does not change the fact that the preposition that art is a dream or a dream is art exerts a subtle influence on all artists, emboldening them to turn their dreams into reality. In a self-account designed not to theorize, the process that dreams come true, in general, is the course of pursuing freedom. This analogy is indeed compelling, as in the virtual world there is no place freer than in a dream, and in the real world there is nothing freer than art. That is why most of the artists in our world are freedom-loving and freedom-pursuing. The same is true for the classical poets who claimed to be “fettered dancers”. Their goal is to “dance” rather than “be fettered”. The only difference may be that they dance in fetters, which is their only means of pleasure. In this sense, art is the synonym of freedom.

Nevertheless, describing the relationship between art and freedom from Freud’s perspective is a vivid and rational process. It is also the predicament all artists are in while trying to struggle out of it, though art and freedom sometimes do not seem remotely connected. The freedom Chen is pursuing is often manifested in the flight-taking process, and imparts on-the-journey towards touch. Unless she does not put herself into such a process, the freedom may seem abstract. As a matter of fact, freedom is not abstract, but philosophical. Freedom is concrete and perceptual.

Albert Camus said in his youth, “I exist, therefore I rebel. I rebel, therefore I exist”. This statement reveals the fact that people are not born with freedom. Jean-Paul Sartre gave an even deeper insight. He said something to the effect that all of us are born accidentally into this adult society. Therefore, we do not have essence. We have become, since we were born as beings essential to others. Together, we constitute an essential group. Such existentialist concepts were widely accepted in the mid-20th century and left an indelible mark on generations of people born accidentally, especially those who are destined for an artistic career.

I did not have a thorough background check on Chen Xi’s past, family and her feelings in adolescent years but I can understand what she was like from the following three relationships that no one is immune from. They are intergenerational relationships, teacher-student relationships and hierarchical relationships. These relationships constitute the basic background thus dictating how we grow and give rise to people’s initial rebellion. The most sensitive of us become premature, and thus depressed, frustrated and indulgent. Premature, in this context, refers to what we may realise early on as the scarcity of freedom in our world, and we struggle to live under these three repressive relationships. Or else, pursuit will not become mania, paranoid and thus disgusting challenges and rebellion, or appropriate or inappropriate self-abuse.

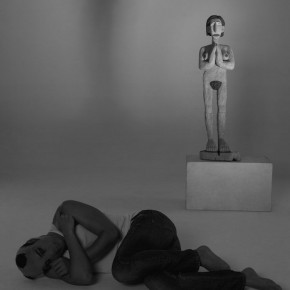

I tried to examine Chen’s personal observation as a woman artist by describing the works of her early career. Her works are like an impartial onlooker and poker-faced narrator, nagging about trivial matters. Her wild style has indicated the young artist’s preference for expressionism and highlighted the conflicts between her artistic style and daily trivia involved in her works. In other words, the more trivial subject matters are in her early works, the more candid and unconstrained her style is, so much so that the conflicts between her style and subject matter are irreconcilable. And it is this conflict that constitutes her personal rebellion against social conventions. I did not make this point in the early discussions in Chen’s career, if it had not been for her two subsequent series, i.e. “The Emperor’s New Clothes” and “Those Remembered” as well as the styles thereof, which present a sharp contrast to the works early in her career, the conflicts hidden within the said early works couldn’t have stood alone. With the two subsequent series that are stylistically distinct from her early works, Chen’s artistic traits have been effectively highlighted.

Thus far, Chen’s works can be categorized into expressionism and symbolism in terms of style and into three distinct groups in terms of subject matter. In her early career, Chen was more of an expressionist, painting details in the kaleidoscopic world with her thick, forceful touches, into sturdy and somewhat clumsy moulds, and with exaggerated, showy hues. Chen’s works in this period can be classified under “New Generation”. With boring trivial life as the subject, her works attempt to end the domination of conventional, grandiose style of paintings on revolution-related subjects, a style that has been formed since 1949. She hopes to free China’s paintings from the din of monotony, so that paintings in China can reflect, in a diversified way, everyday life in the country.

With respect to the significance of the “New Generation” style in ending the domination of the conventional, grandiose style, I would like to reiterate the standpoint I made earlier during discussions about Chen’s works:

“Today’s artists are already unfamiliar with the grandiose style of paintings. Only those who care about National Art Works Exhibition would rack their brains, trying to figure out works on what subjects may become the most likely candidates. Despite the Ministry of Culture’s substantial spending on a program encouraging ‘Historical Paintings on Revolution’, this subject has already become one of the many subjects of artists’ own discretions. Painters, especially those with a keen eye, would rather follow their own hearts than get obsessed with whether the subject is ‘important’ enough.”

I also underscored the values and beliefs closely related to her personal existence:

“I’m afraid that some may not duly appreciate the changes brought about by Chen’s works and the implications thereof if they fail to reflect on this. In my view, the changes are revolutionary. When we keep on advocating the idea of ‘seeking inspiration from life’, we are actually debasing the life we have led and are leading. We are used to seeing everything through rose tinted glasses, thus failing to see anything but grandiose. And when we try to seek inspiration from life without removing the glasses, we seldom break the stereotype and create outside the box. Only by removing the glasses, can we see things as we wish and therefore, understand life and art as they are.”

The discussions we made relate to the change of values. When we then look at Chen’s creative practices, it wouldn’t be difficult to understand the meaning of what she referred to as “flight of freedom”. It means the escape from the pressure of creating works on “grandiose” subjects and from the institutionalised and, therefore, suffocating exhibitions. This is the essence of freedom. In this sense, freedom and flight are intrinsically consistent, like two sides of the same coin.

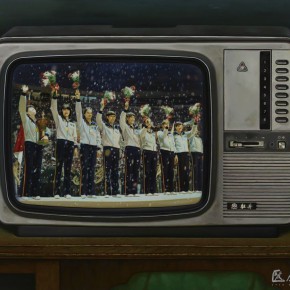

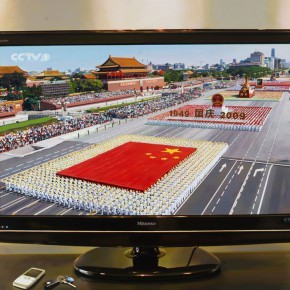

Interestingly, once people begin to look closely at Chen’s two series subsequent to her early day’s expressionist works, they will discover the rift between freedom and flight. Chen’s shift from the portrayal of daily trivia as an onlooker, to the cool-headed craze about typical daydreams, and the gaze of classic snapshots on TV reflecting the artist’s struggle between freedom and flight. Chen is torn between freedom and flight, afflicted by the confusion thereof. She also has a hard time with the tug-of-war deep down, between being born gracefully and the potential of the mocking of death, and between sex and gender, which is unique to women.

Chen entitled the new collection of her works during three stages of her artistic career “Better New than Old”, yet most of the works collected are from the first stage. This contrast points to the longstanding conflict within her, a yearning for both freedom and flight.

In this collection, the “old” refers to her wild expressionist style, whereas the “new” refers to her new-found cool-headed style. A number of paintings of naked women, adopting suggestive postures as if they were bored, and thus with slightly triumphant expression, stand right in front of the spectators. Soap bubbles cover the private parts, shielding lustful gaze. The paintings are so large that they provoke a reaction similar to impotence among the viewers, making them shy yet yearning to gaze. As a result, in the exhibition hall, two conflicts arise. In the paintings, the naked women that are calm and suggestive conflict with the bustle and indulgent life of city in the background. The conflict is further conflicted with viewers’ gaze and avoidance, making the exhibition a part of and extension to her works.

As I stated earlier, on the surface, it seems that this series of Chen’s works can be interpreted in Freud’s dream theories, but Chen didn’t try to explain or prove anything during her creation. She was in a state of flight of freedom, just as she herself explained. It Is when her works were completed and put on show that viewers found out that her works resemble Freud’s typical dreamy scenes, and were confused about whether this signifies Chen’s freedom or flight. Viewers also face a question. Which part of the paintings should they look at? This can distinguish those that appreciate it from voyeurs. As an artist, I believe that Chen Xi was watching the viewers as well. Appreciation and glances are actually two sides of the same coin. Artists themselves are conflicted beings. When Chen painted the city, she was taking flight, escaping from the superficial hustle and bustle of the city, from the graceful lifestyle and from the nature of better taste and higher qualities. Yet when she painted naked women, she was enjoying the freedom, carefree, willfulness, curses, happiness and the release of feelings.

I think naked women under female artists’ brushes are intrinsically different from those under male artists’ brushes, a phenomenon determined by the time-honored tradition in patriarchal society as well as gender difference. To men, the most boring nude may be the aesthetic nude, as it is a typical hypocrisy, pretence of disinterest and fake nobility. The most intriguing nude must be those designed for the view of the opposite sex, as it involves hormonal satisfaction through voyeurism. Women artists, however, paint naked women in a way entirely distinct from that of male artists. To take flight from being watched, naked women in paintings resort to ridicule and flirt in reaction to men’s glances and gaze, hoping to present to the world the role of women and to turn flight into freedom. That is why Chen chose the name “The Emperor’s New Clothes”. Yet it remains a moot point whether the flight can be turned into freedom. Chen Xi is an artist, not philosopher, so it is not her responsibility to give a rational answer. On this, Chen Xi is rather emotional. She is free and takes flight. She looks on and gazes. She expresses and portrays.

This character has made who she is today, focusing on “Those Remembered”. She has shifted from wildness to on-looking and to reflection, a reflection on memories.

Eighteen frames have recorded 18 historic moments. These moments were witnessed on TV, and therefore were recognized by the viewers. My point is that these 18 frames will no doubt evoke viewers’ memories about these historic events and their perceptions. But is it the case that Chen Xi, with keen senses, just wants to paint the 18 undoubted moments, which will only trap living memories in the swamp of death. No, this is absolutely not her intention. I am sure of that. Paintings about memories themselves are powerless. Yet when we connect the dots – the 18 historic moments, the memories about these historic events can be evoked, and the paintings will carry extended social meanings. At least, Chen Xi herself believes so, or else there is no point of her devoting so much paint on the TV set, the vehicle of these memory evokers, as well as limited details related to the TV set such as the desk, mirror, cell phone, car key and wallet. Chen’s works are not to present the history as it was or evoke vague memories. They are not artists’ responsibilities. As always, she searches and proves freedom, hoping that freedom no longer needs to be defined by flight and that flight itself means freedom. For the memory of “Those Remembered” have no freedom. They are imposed by the establishment and dictated by the way people in power tell the history. All this is effected through and evidenced by the TV set in the living room. Painting the TV set is the portrayal of flight. Yet the TV set, the industrial design that finds its form in different makes in different periods, is the most powerful weapon to subvert the flight. It forces us away from the familiar scenes on TV to savor freedom. That is Chen Xi, a woman artist who tries to seek freedom from flight and hopes to define flight with freedom.

Now, the 18 paintings, collected in the “Those Remembered” are standing right there. The paintings together with historic moments, industrial design and vivid details have become synonymous with freedom and flight. They are there for people to understand, discuss and choose. Yet freedom or flight remains a question. Not having been solved, this question exists on the wall – in a more visualized way – in the form of paintings, jeering at us.

The conclusion is clear. To Chen Xi, the viewers and society that is forced to remember in this way rather than another, freedom or flight remains a question. This is a question of this age. This is a personal question, an artistic question, and a question with no answers. This is a perceptual question, and also a rational one.

Courtesy of the artist and YANG Xiaoyan.