We live in a digital age. From the land to the sea, from the blue planet to the unfathomable depths of space, from our bodies to our thoughts, emotions, hobbies and private embarrassments, everything can be broken down by digital technology into bits of code and stored in the cloud, from where it can be analyzed and categorized with big data, compiled into data samples and information blocks to be disseminated and shared, and put to use as tools of politics, economics, culture and society.

I do not know when it was that digital technology became as important to us as air and sunlight. It is hard to imagine what tragedies would befall humanity if the global internet were to go out for only a single hour. Digital technology is deeply embedded in contemporary human life, which naturally includes art as well.

In the early 20th century, Walter Benjamin made keen discoveries regarding the influence that the coming industrial age would have on culture, particularly the drastic changes that mass mechanical reproduction would bring to the production and consumption of the work of art. In his treatise The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, he posited that the originality of the artwork was unattainable for reproduction technology, and that art lacking an aura would lose the “cult value” of traditional art’s close connection to religious ritual. The abundance of reproductions would lead people to lose their reverence for art. As the mysterious distance from the artwork disappeared, mechanically reproduction artworks not only pulled art down from its altar for the first time in history, it also gave rise to a closer relationship between art and the masses. The work of art had become a consumable product, and was bestowed with many social functions.

Chen Qi, Notations of Time—Jar, details

Benjamin’s theory accurately predicted the developmental trajectory and ecosystem of art that followed, but it had another side effect, which was a misunderstanding among the public regarding the industrial reproduction of artworks and low value. Original plural artworks and mass mechanical reproduction of artworks are two completely different concepts. Since both are plural in nature, however, they are often discussed as one. For instance, print art is often misunderstood as a mechanical reproduction. This leads me into thinking on reproduction technology, reproduction art and the relationship between artist and technology in the creative process, whether the reproduction is manual, mechanical or digital.

In fact, since its very beginning, art has had an instinct for self-evolution and reproduction. From tablets, templates, rubbings, molding, woodcut, engraving and lithography to photography and cinema, the dissemination, development and evolution of art has gone hand in hand with reproduction technology. In pre-industrial society, the work of art was mainly connected to manual reproduction. In industrial society, the reproduction of the work of art was marked by mechanical and quantifying trends. The American scholar Brian Arthur believes that technology has the ability to evolve like a living thing, and even undergoes genetic mutation. In the progress of human civilization, each development in technology coincides with the emergence of a new art form. This art born of new technology does not replace traditional art forms, but it does influence the development of traditional art through the cultural environment its technology creates.

The invention of Daguerreotype photographic technology by Louis Daguerre in 1837 changed the ways humans produce and spread images. Photographic technology shifted painting from the objective re-creation of images to the subjective expression of artists’ minds, giving birth not only to modernist painting, but to photographic art as well. Forty one years later, Thomas Edison began researching the moving image, building on George Eastman’s roll film and the work of William Dickson, Edison created an embryonic cinema with footage of a moving horse. The events that followed demonstrate that cinema art never replaced its ancestor photography, just as television never replaced cinema. Likewise, the independent media videos currently spread and consumed over 4G networks have not replaced television. In 1957, Russel A. Kirsch used a computer to scan a photograph of his son Walden, creating the world’s first digital image, in a development no less important than the invention of film. When Benjamin Franklin carried out his dangerous experiments with lightning in July 1752, he could not have known how, in a few centuries, electricity would become a fundamental source of energy for humankind. If we compared the photographic image to minerals, then the digital image is minerals on a vehicle travelling down the highway, able to be conveyed to any corner of the world and turned into a variety of products. From John von Neumann’s creation of the first computer in 1946 to today, digital technology has come to permeate every aspect of social life, and an indispensable technical method means all manner of artistic creations.

Chen Qi, Notations of Time—The Song of Chu(Chu Ci)

I grew curious about digital technology in 1991. With no experience in operating computers, I spent virtually all of my savings to buy my first 486 PC, at a price of 36,000 yuan, beginning my own digital age. My application of digital technology in the artistic creative process has been full of contradictions and confusion, which, after twenty years, I have come to ascribe to the conceptual conflicts between artistic creation and digital technology.

I have always liked design, and have worked in various design fields from graphic design to environmental art. I had an high success rate with my clients. If painting did not have such a powerful attraction for me, then perhaps today I would be a decent professional designer or a small business owner. The greatest differences between design and painting are in terms of the subject they serve and the ways in which they are exchanged. In painting, the painter can often engage in freewheeling journeys to his heart’s content. It is the opposite with design, where the designer must have a thorough understanding of the client’s needs, including their aesthetic tastes and emotional projections. As a result, the designer often has broader social interaction than the painter, and is more sensitive to social changes, aesthetic trends and technological advancements. Perhaps it is my instinct as a designer that allowed me to sense the massive productivity that computing would bring to design.

In the twenty years between my first color-layer paintings on the computer and my mastering of the Founder Group Digital Publishing System and Adobe imaging software, I have spent time in both the art and design pools, with little interference between the two. In creating printed art, I have followed the traditional technical norms of the medium, carrying out each step, from drawing to plate division to copying, engraving, revision and printing, entirely by hand. This process did give rise to many new desires for artistic expression, but it never led me to consider digital technology and artistic creation. It wasn’t until I came across a series “print artworks” that had been created using Photoshop and an HP inkjet printer that my attention was drawn to the relationship between digital technology and pure art. I was unmoved by those A3-sized artworks created using the simplest of Photoshop techniques, but these “digital prints” appeared in many exhibitions. For this reason, it became necessary to sweep away the boundaries between print art and digital art, and to clarify the relationship between the creations of artists and digital technology.

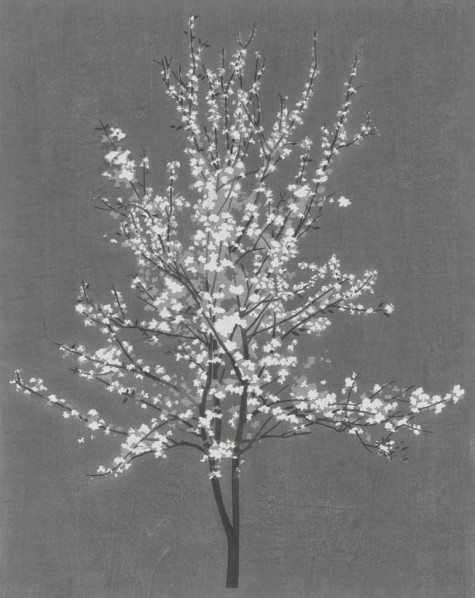

Chen Qi, Seeing Pear Flowers Again, 2014; waterblock print, 100x80cm

I am of the opinion that not all plural art is print art. There are many other forms, such as sculpture, photography and cinema. The arrival of the digital age gave birth to a digital art that uses digital technology as its linguistic structure and expressive medium. Artworks created by inkjet or 3D printing are not print art. The most marked trait of digital art is not its plurality but its virtual, interactive, hyper-connected and editing nature. Hence, digital print art is a false concept, one traded by those who are unclear on the essential traits of print art and have no understanding of digital art.

The imprint is the essential trait of print art. It is a mark with special connotations left consciously by the artist through the medium of printing. Just as the image of music is formed by notes and melodies, the image of the print is formed from the imprint. No matter which approach you take to printing, the imprint is the unique fingerprint of all prints. Looking back over the history of print, we see that the expansion of the print’s expressive power has always been inextricably linked to new technologies and materials. From simple woodcuts to complex photolithography, we have always been able to find an artistic spokesman for each leap in technology in print. In today’s digital era, digital technology and traditional printing technology should find organic integration, with no mutual exclusion. Printmaking should certainly make use of digital art to bring about innovations in artistic form and an expansion of artistic expression.

Later, I employed digital technology in many ways in my creative methods, and have now grown accustomed to using digital thought processes in my artistic creations. In my mind, there is no major difference between the pencil, the brush, and the pointer on the computer monitor. My artistic concepts and individual emotional experiences can be digitally stored on a hard drive or sent to the cloud, and can be free of any spatiotemporal limitations. In my digital creative thinking over the past decade, I have grown accustomed to combining fragments from the depths of my consciousness or spiritual world to create sweeping individual narratives. Digital technology can take the scattered, dismembered segments of life, and recompile them in many ways, reconstructing and restoring a more complete life experience.

Chen Qi, Scrap Gold (Triple), 2015; waterblock print, 380X540cm

The digital study for the artwork Scrap Gold carried on intermittently for over a year, much of it completed during my travels, as if weaving together the golden flecks of time. This picture measuring 380 cm x 540 cm was precisely divided into 96 printing plates, which were then printed using Chinese traditional water woodcut printing techniques. I believe that such a large, highly detailed and expressive artwork would not be possible without digital technology. The perfect integration of modern digital technology and traditional water printmaking has imbued this artwork with a spirit of experimentation and the future.

Last year, the 78 year-old British artist David Hockney came to China. In discussing digital technology, he said that painting with an iPhone is not a surrender to technology; it is just a medium. Truly, for the primitive cave painter, pencils, brushes, paints, papers and canvases would be mystified by technology. When people gradually grow accustomed to artworks or reproductions created with new technologies and materials, they come to realize that art actually hasn’t changed. What has changed are the artists, who have become intellectuals with ideas and products. There are all kinds of artists. Thus, in contemporary society, there is cheap art, expensive art, and art that is still high on its pedestal. The question of how art is produced is no longer important.

Marshall McLuhan believes that medium is all tools and technologies as extensions of the human organs. When I sit in my studio every day, operating the digitally controlled machine bed, and watch the fast-rotating knives or rays of lasers cutting out the elegant curves in my mind on the wood according to constantly shifting coordinates, I think, this is art, dammit!

Chen Qi

October 22, 2015

Courtesy of the artist and Amy Li Gallery.