The modernization of Chinese paintings and the views on Western art are the most thought-provoking part of Lu Chen’s art and his artistic thoughts, and he has a basic judgment and practice direction for this topic: “the marriage of distant relatives”. Although it is not a completely new argument – in the Republic of China, there were similar ideas such as the “Marriage of Chinese and Western Art” – but they had different meanings because they were proposed in different times and their purposes were different. Lu Chen mentioned in the theory of “the marriage of the distant relatives” that there were some arts that were possible to be blended into Chinese painting, and he believed that it was better for the art to be farther away from Chinese paintings, while it was a possibility of connection – because, after all, it was called “the distant relatives”1. These “distant relatives” includes two systems, one is the non-high-level art including folk art, primitive art, and children’s art; the other is Western modern art. It is worth noting that the primitive art, folk art, and children’s art were all important sources in the process of the emergence and development of Western modern art. There are common ideas in both. Therefore, the resources for the modernization of Chinese painting were eventually fixed on Western modern art in his arguments.

Through the research of his writings and works, we can see that he attached great importance to Expressionism, Cubism, Fauvism, Surrealism, and Futurism. He especially focuses on Cubism, Fauvism and Surrealism, which were often used in the creation. Why didn’t he choose the various schools of art after World War II? This is worth considering.

Of course, it may be considered that when he modernized Chinese painting in the early 1980s, modern Western art had not been comprehensively introduced to China. But in reality, it was not true. Even in the 1960s and 1970s, a small amount of Western modernist books or images were still circulated in the colleges and among artists. Moreover, the Zhejiang Academy of Fine Arts (now the China Academy of Art) has continuously published “Guowaimeishuziliao” (renamed the “Meishuyicong” in 1980) since 1977, The Central Academy of Fine Arts has continuously published “World Art” since 1979. In the same year, the People's Fine Arts Publishing House also began the publishing of “Waiguomeishuziliaoyibian”, in addition, Shao Dazhen and other experts in the field of Western modern art history have also translated many related books and the comprehensive art magazines such as “Fine Arts” have also begun to introduce Western art.

In the above materials, various types of Western modern art were presented and can be easily found in the library of the Central Academy of Fine Arts, where Lu Chen worked. However, Lu Chen still focused on a few schools over a certain period of time. Perhaps it was related to Lu Chen’s artistic experience in his early years: He had studied Western painting at the Suzhou College of Fine Arts, which was founded by Yan Wenliang and others, and it was a key experience for him. Yan Wenliang studied at the école nationale supérieure des Beaux-arts de Paris, France, from 1928 to 1931. It was exactly the period of the artistic style as mentioned above and it was also his most intuitive experience in Europe. The influence of the Impressionists and his knowledge of other Western art were passed down to the students of Suzhou College of Fine Arts.

Not only that, some characteristics in Lu Chen’s discussion and adoption are as following: firstly, he did not pay attention to the continuity of different artists, works of art and the schools of art in Western art history. Secondly, he did not pay attention to the external causes of artistic works and artistic phenomena. Thirdly, he paid attention to the painting itself, and the form of painting. So he talked about the specific role of drawing on Western art: the destruction of the natural form, the negation of the focus perspective, and the symbolic form symbolized by the movement and time. 3 Through Lu’s choices of modern Western art and several individual understandings. We can see his purpose: to correspond to his particular needs. All these requirements are limited to the internal issues of painting, that is, the issue of the ontology of art and his fundamental purpose was to transform Chinese painting from the ontological sense. For him, “vision” and “aesthetic” were the two most important things, which was perfectly in line with the concept of modernism in the first 30 years of the 20th century. These modern arts were distinguished from the avant-garde, such as Dadaism that was the artistic concept of intervention in society in advance, of the same time, but failed to focus on the innovation of the art. This is directly related to the new ontology of the ink and wash that Lu attempted to establish, and it can also explain the concept and practice of the “ink-and-wash composition” advocated by him. At this point, they reached a consensus.

It is worth noting that he had a clear direction for the transformation of Chinese painting, and it was for the local Chinese art history. On the one hand, through this transformation, we can see the opposite of Lu Chen’s art, that is, realism. After the reform and opening up, he thought that there were problems in the style that has led Chinese art for a long time at that time: “In the past, the basic teaching of the Department of Chinese Painting has great flaws”, on the one hand, it was “affected by the Soviet Union, of a blind faith in sketching, believing that the sketching training was all-powerful.”4 On the other hand, the ontology that was in need of being re-established can’t come from Chinese traditions – both are reflected in the artistic practices of Lu Chen, and other revolutionary artists at that time. It shows that the innovation of Chinese painting, as well as the purpose and pertinence of innovation, have considerable common practices and historical inevitability. Therefore, they all chose Western modernist art in the first 30 years of the 20th century and used it to intervene in the transformation of Chinese painting.

How was the reform carried out? For Lu Chen, there was an important opportunity to see the “The Hiroshima Panels” by the Japanese artists Maruki Iri (1901-1995) and Maruki Toshi (1912-2000). Japan was different from China, while modern China became a socialist country after it entered the globalization system, Japan did not. Therefore, in terms of the choice of Western art, Japan has not been completely transformed by the realism system, but it chose the Western early modernism tradition. This tradition exactly corresponded to the innovation choice of Iri and Toshi Maruki, and Lu Chen. Lu Chen was inspired by the early Western modernist factions to conduct the “integration of China and the West”, while Maruki Iri’s “Japan-European Integration” also originated in this art. Therefore, Lu Chen had a resonation with “The Hiroshima Panels” by Maruki Iri and Maruki Toshi, and they had a substantial impact on him.

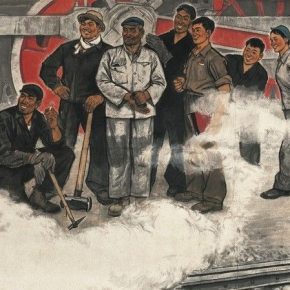

Maruki Iri’s teacher was Tanaka Raisho (1866-1940) 5, who was a relatively traditional Japanese painter, rather than an artist learning from the West, nor a reformist. In addition to Maruki, Chinese painter He Xiangning was also his student, and He Xiangning completely inherited his style. In addition, Gao Qifeng once learned from Tanaka Raisho for a short time. But Maruki Iri later left Tanaka Raisho and began to pursue a new modern Western-style art. It was a special period for Western modern art of the 1920s and 1930s and the earlier Impressionism and post-impressionism spread across Japan. Therefore, the couple Maruki did not inherit their teacher’s artistic tradition in the later creation, but turned to the early Western modernist art, especially the post-impressionism and Fauvism styles, which he based his creations on “The Hiroshima Panels”, then influenced Lu Chen’s creation. “The Hiroshima Panels”, a work of pacifism modernist style, is comparable to Picasso’s “Guernica”. As far as the impact of “The Hiroshima Panels” on Lu Chen is concerned, it reveals a Cubism superposition effect, and Lu Chen learned the early style of modernism from this piece. He began an experiment with modernism in 1980.

These two pieces helped him to learn how to use the reconstructed Chinese paintings to create on a major theme or macro theme, with a way different from realism, while it was difficult to deal with such a major theme with the method of traditional Chinese painting. Of course, although the new modern Chinese realistic painting tradition is good at dealing with major topics, he was opposed to realistic painting. Therefore, he immediately turned to early Western modernism from a practical perspective. In 1980, he created “Common People Went to Beijing for Petition”, which was different from the “Miners Figure” in two ways. On the one hand, “Miners Figure” was still political, with a distinctive socialist and realism concept, while “Common People Went to Beijing for Petition” basically ignored this factor. On the other hand, compared to “Miners Figure” compromising the traditional and modern, the new work emphasized cubist-style experiments more. In fact, “Miners Figure” was mainly created by Zhou Sicong. It can be declared that Lu Chen’s artistic creation during this period was strategic and he had a clear purpose of transforming Chinese painting through Western art, thus to make Chinese painting realise modernization.

In order to illustrate this strategic quality, I would like to compare the manuscripts of “Common People Went to Beijing for Petition” and the finished painting. It is obvious that both are separate. Manuscripts are the results of the sketching of modern Chinese paintings, which are reflected both in the shape and the brush-and-ink effect; the cubist style is clearly seen in the composition and expression. The relationship between the sketches and works is only maintained by the same characters. If we compare the relationship between Picasso’s drafts and works, we can understand it better. There is a similarity of style between Picasso’s “Les Demoiselles d'Avignon” and Lu Chen’s finished piece of “Common People Went to Beijing for Petition”, but we find that they are completely different when putting them together. Through these comparisons, we can see that Lu Chen still maintained a realistic mode of thinking when he collected material, but he tried his best to weaken the socialist realism thinking and to blend the collected realistic images into a cubist composition and expression system, when he was creating. This is the stage of his initial experimentation, attempting to transform Chinese painting.

After the mid-1980s, Lu Chen was more concerned with Fauvism and surrealism, but as I mentioned above, his choice was clear-cut. He was more concerned with psychological expression in the part of surrealism. Lu ignored the Dadaism based on absurd splicing and social intervention, and early surrealism, but paid attention to post-surrealism since the mid-1920s, focusing on the psychological performance, especially the works by Joan Miró (1893-1983) and other artists. In Lu Chen’s creation, this genetic relationship can be clearly seen.

“Searching for the Way and Change – Lu Chen’s Art Exhibition”, displayed at the Art Museum of Beijing Fine Art Academy in 2017, presented a series of abstract works created by Lu Chen in the 1990s. Lu Chen started the experience of modern ink painting in the 1980s, and then went to France in 1987, returned to China to set the course of “ink composition”, he always started from the form to rebuild the noumenon of modern Chinese painting, and it inevitably resulted in making the end of formalism – abstractionism, according to the logic of art history. In this period, Lu Chen became mature and started to gain from his achievements. Moreover, compared with his abstractionist works, the piece of “Qingming Festival” and the similar works have been of more concern for the Chinese critics and art historians when they studied the history of modern art. Through the analysis, compared with other early experimental works such as “Common People Went to Beijing for Petition”, “Qingming Festival” did not directly adopt the expression and composition of Western modern art, but people can feel the thing that he previously tried best to integrate hidden in it. Moreover, the relationship between these works and traditional Chinese paintings has become intimate again.

What the “Qingming Festival” depicts is not a vertical perspective space. There is not any superposition between the images, but they are juxtaposed in a plane. At the same time, these juxtaposed images are of various sizes, so that it seems to imply a perspective, but he neither carefully portrayed the “nearby” figures, nor simply portrayed distant figures. As a result, a visual contradiction and conflict appears which seems to have and not have a perspective. This contradiction was precisely what Cézanne tried to express on his screen. However, in the specific expression, Lu Chen used a form that was similar to the rubbing of the portrait stones and bricks, rather than the basic structure of objects of Cézanne’s style in the creation. In this sense, this series of Chinese paintings further promoted the purpose of the ink-and-wash composition to a new stage. Seen from the results, it has also been favored by the mainstream cultural atmosphere integrating modernization and nationalization. Seen from the background of the creation, it was also in line with the requirements of cultural re-nationalization in the process of the dramatic changes in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe.

Compared with Lu Chen’s case of art history, many other artists also had the intention to transform Chinese paintings by introducing Western art, so that Chinese paintings can be modernized. Moreover, their choices of Western art often overlapped. It may indicate that the history of Chinese art had consciously entered the modern era. In the modern history of China, “revolution” and “founding the country” were dialectical contradictions. The world revolution, especially the socialist world revolution, requires the breaking of the countries’ borders and the establishment of a global proletarian alliance, which means abandoning the historical tradition and participating in the construction and ownership of a new common world culture; the nation state demands the reconstruction of the countries’ borders and administrative systems, which inevitably requires the traceability of the countries’ history and culture in order to obtain the historical legitimacy of the new countries, which in turn has led to the need to restart the tradition. Therefore, between the new global culture of universalism and the traditional culture of Chinese characteristics, there are contradictions between the old and the new, between China and the West, but they are all needed by modern China at the same time.

In the same way, the modernization of Chinese art, including Chinese painting, has also encountered this problem. Obviously, the art style that was completely copied from the West can’t adapt to the needs of “building the country”, while the absolute tradition can’t correspond to the needs of “revolution”. Under the requirements of seeking new ideas and universalism, Chinese painting was renamed Color ink painting in the 1950s to remove the national & regional labels of the painting species, and to move toward cosmopolitanism. However, in 1978, especially in the post-revolutionary atmosphere after 1992, the tradition has been re-introduced to meet the symbol of the state’s main body in the new global order. Lu Chen’s experiment in modern Chinese paintings was initiated in such a conflicting context. Therefore, until the 1990s, the emergence of “Qingming Festival” and similar works has coordinated the contradiction between both and proposed new ideas for the innovation of Chinese painting.

*I would like to express my thanks to Wu Hao who inquired into the Japanese data for me.

Notes:

1 Lu Chen: “Development and Innovation”, edited by Beijing Fine Art Academy: “Lu Chen’s Review on Ink Painting”, Nanning: Guangxi Fine Arts Publishing House, p.102 – p.103.

2 Yan Wenliang: “Style and Genre”, Lin Wenxia: “Modern Artists: Painting Theory·Works·Lifetime - Yan Wenliang”, Shanghai: Xuelin Press, 1996, p. 22.

3 Lu Chen: “Line Drawing”, edited by Beijing Fine Art Academy: “Lu Chen’s Review on Ink Painting”, Nanning: Guangxi Fine Arts Publishing House, p. 115.

4 Lu Chen: “Conception of the Teaching System”, edited by Beijing Fine Art Academy: “Lu Chen’s Review on Ink Painting”, Nanning: Guangxi Fine Arts Publishing House, p. 165.

5 Tanaka Raisho was a Japanese painter living from the Meiji Period to the Showa Period. He was an inspector of the Art Exhibition of Japanese Ministry of Education, a member and an inspector of the Imperial Academy of Art, a member of the Japanese Painting of Japan Artists Association, an imperial painter. Tanaka Raisho was born in Ōchi District, Shimane Prefecture in 1866. Tanaka Raisho first studied under Mori Kansai (1814-1894) of Maruyama & Shijo School in Kyoto. After moving to Tokyo he studied under Kawabata Gyokusho (1842-1913), an inheritor of Maruyama & Shijo School, and he returned to Hiroshima in 1924 after the Great Kanto Earthquake, and died in 1940. Tanaka Raisho was famous for his landscape paintings.

Translated by Chen Peihua and edited by Sue/CAFA ART INFO