Over the past decade or so, contemporary art criticism from the perspective of feminism has risen rapidly in China1 to the point that any creative practices and exhibitions by female artists can be commented on with the origin of concept or theory.

Zhang Yanzi and her works are naturally included in this category. From the curator’s emphasis on the gender attributes of her works2 to the political appearance of where her solo exhibition “Dangerous Balance” (2023) was held3, all of them are intentionally or unintentionally mixed with the labels of “gender” or “ism”. What’s more, some would say: “Her appearance can challenge any female star who graduated from an academy of drama. Instead, Yanzi is an extremely talented artist...”4

Rather than being the curator’s fabrication, these comments are more like the artist’s deliberate “creation”. Zhang Yanzi is good at creating a strong “feminine” atmosphere in her works. Whether it is the delicate brushstrokes, the perfect rendering, the light pink and purple tones, or even the fruits and utensils full of gender-based metaphors, they all seem to declare without reservation: such works are truly created from the hands of a woman.

But the subtle thing is: if you stay in this atmosphere for too long, it will be like being trapped in a maze, feeling that there is light ahead, but it is difficult to start; naturally, you will not be able to explore the hidden realm: there, it seems to have nothing to do with gender, but how can it be said to be “irrelevant”?

—This is probably the “paradox” featured in Zhang Yanzi’s work.

The first time I saw her work in person, I unconsciously had this trance feeling. At that time, the only thing I could be sure of was: this situation cannot be simply described by Western feminist thought5.

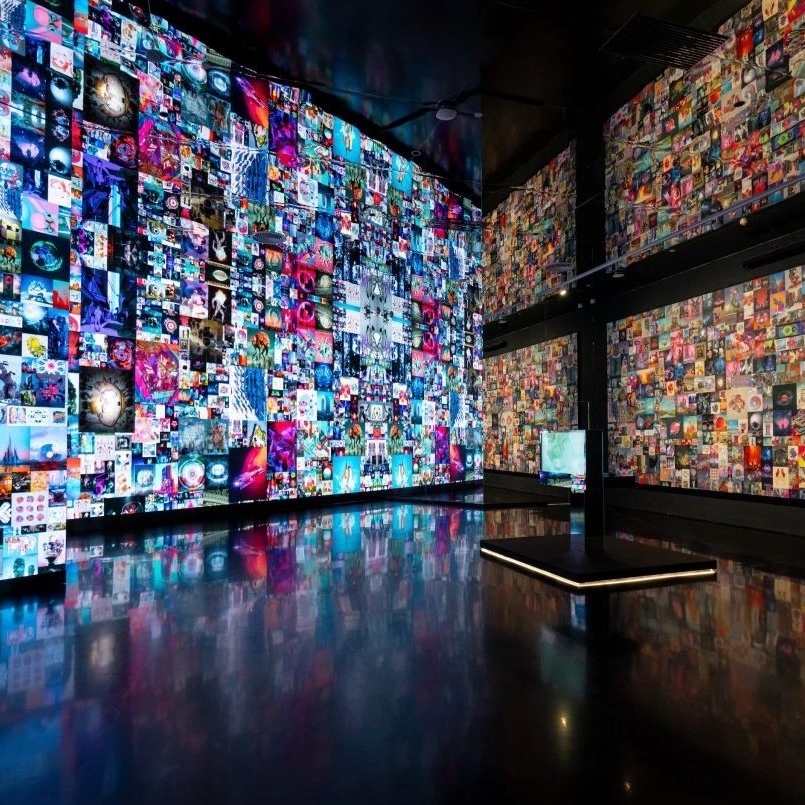

Exhibition View of "INDIVISIBLE: Zhang Yanzi Solo Exhibition"

Exhibition View of "INDIVISIBLE: Zhang Yanzi Solo Exhibition"

The Harmony of Technology, Cognition and Art

Regarding the relationship between “artistic personality” and “artistic laws”, I believe in the view of Lionello Venturi (1885-1961): Compared with the “personality” of an artwork, the so-called “law” is transient, changeable and non-essential, changing with time and place6. In other words, “artworks do not exist naturally, but are objects made by individuals with thoughts, feelings and rationality, that are part of a larger social environment. It is this overall situation that determines the significance of the artwork itself”7.

If we follow this line of reasoning, it means that as long as we want to understand Zhang Yanzi and her works, where her subtle “paradoxical” state comes from, and what the relationship between her and the so-called “feminist art” is, we should start with her “individual attributes.”

Zhang Yanzi was born during the “Cultural Revolution”. If we understand her in the context of the process of Chinese women’s liberation8, we will find that this is an era worth analyzing.

—During this period, “women” were shaped holistically; in law, the civil rights of men and women were formally declared; in action, gender equality was promoted through political movements and administrative means. Because its “power and achievements were far beyond the reach of all feminist movements, it also surpassed any form of feminist movement”9.

The awareness of gender equality was planted in Zhang Yanzi’s mind during her childhood, and she can still blurt out the “March 8th Red Flag Bearer” and “Women can hold up half the sky” that were advocated back then. The relatively relaxed environment for girls also fostered her curious and rebellious personality. Her favorite “toys” were medical needles and stethoscopes. However, at that time, she may not have expected that one day these would become the subjects of her own creations, such as “Registration” (2012) and “Painless” (2013).

Exhibition View of "INDIVISIBLE: Zhang Yanzi Solo Exhibition"

Exhibition View of "INDIVISIBLE: Zhang Yanzi Solo Exhibition"

—It emerged after the reform and opening up in the 1980s and continues to this day. During this period, the subject consciousness of women (no longer “妇女fu nv", which refers to women beyond 14 years old in China) began to awaken, intending to separate “self” from “society”, “individual” from “group”, and “female” from the gender cognition of “men and women are the same”. The theme of this period was “self-awareness”. At the same time, Western feminist thought began to be introduced to China and it entered the field of academic research and public opinion.

Zhang Yanzi’s adolescence coincided with the beginning of this period, that is, her personal self-awareness of female consciousness and the transformation of the society’s overall cognition of women were synchronized. In junior high school, when she began to systematically learn painting, she devoted herself to studying “beauties”, especially the ladies in Dream of Red Mansions. This aesthetic interest lasted for more than 20 years throughout her entire adulthood. The highlight of her development at this period was the bronze medal she won at the 10th National Exhibition of Fine Arts in 2004 with her work “Red Rose and White Rose”.

In 1986, Simone de Beauvoir (1908-1986) published The Second Sex (1949) in China. Although it is not known whether this feminist text of great significance in the 20th century was Zhang Yanzi’s bedside reading, it is conceivable that if she had a more lasting attention and enthusiasm for the feminism that was popular at the time, she would probably go further on this “road”.

However, if retrospecting the overall appearance of her works, it is not difficult to find the “forks in the path”: in 2012, after completing the “The Remedy” series, Zhang Yanzi may have also completed her own creative transformation.

Fragments series, Mixed media, Dimension variable, 2024; Exhibition View of "INDIVISIBLE: Zhang Yanzi Solo Exhibition" at Art Museum of Nanjing University of the Arts (AMNUA)

Fragments series, Mixed media, Dimension variable, 2024; Exhibition View of "INDIVISIBLE: Zhang Yanzi Solo Exhibition" at Art Museum of Nanjing University of the Arts (AMNUA)

As recorded in “Yi Guan”: “From the early death of her parents to the birth of ‘The Remedy’, Zhang Yanzi hid this slow and continuous pain for 10 years.”10—The transformation was not achieved overnight. The artist finally encountered her own problematic consciousness, although this was indeed a “passive gift” in her life experience: pain and joy, illness, life and death... all these are no longer issues that can be blamed by “beauty”, gender or feminism.

In the same year, Zhang Yanzi said in an interview: “Whether there is “feminism” , “female experience” exists. “Feminism” should be a kind of “female experience”, an awakening of women beyond gender-based consciousness in social activities.”11

It can be seen that she did not internalize the relevant theories of feminism into the cognition or judgment of “ego”; instead, she did the opposite and redefined “feminism” based on her own experience and mentality.

The above overview can largely brief the “overall social facts” of this female artist and her works12.

Gender as a “Convenience”13

Another part of the “overall social facts” is implicit in Zhang Yanzi’s own narrative. She said:

As the core artistic language of traditional Chinese painting, the reason why ink and wash is so highly valued is closely related to the position of ancient Chinese literati painting in art history…

I have always believed that Eastern painting, represented by literati painting, has the same characteristics as Western so-called conceptual art in terms of the expression of concepts. Although they differ in time, space and fields, they can be regarded as a “coincidence” cultural fit point in the history of Eastern and Western art. The creation of literati painting is very “self-centered”…

When we look at Tao Yuanming’s stringless qin (Chinese lute), Zhu Da’s strange rocks and thin birds, etc., the vividness and meaning beyond the brushes are all conceptual art from the East. In other words, their creations are very contemporary.14

Perhaps based on this idea, Zhang Yanzi will connect traditional ink and wash language with contemporary art and “harmonize” it in her own creative practice. Here, there is no contemporary “conversion” of traditional language.

However, if art critic Tao Yongbai knew of this statement, she would probably find it incredible. She believes that only “paintings created by female painters, using female perspectives, showing female spiritual emotions, and using female unique forms of expression—female discourse, all these kinds of paintings” can be called “female paintings.” In contrast, literati paintings created by male creators are “male paintings” that represent “male-centered power culture.” Therefore, the history of Chinese painting is a history of the “absence” of women15—how can this... be “connected” with the creative practice and self-expression of a female artist?16

Enjoy Oneself (12 pieces in a series), 2020; Ink, mirror, iron cage, painting: 26×35cm, iron cage: 35×45cm.

Enjoy Oneself (12 pieces in a series), 2020; Ink, mirror, iron cage, painting: 26×35cm, iron cage: 35×45cm.

Returning to the historical context of Chinese painting, Tao Yongbai’s research on the history of painting from a gender-based perspective can be said to be stating a historical fact.

However, when it comes to the era when Zhang Yanzi grew up, the gender division in literary and artistic transmission was not necessarily so clear. Under the principle of “men and women are equal,” the landscape civilization and philosophy of life reflected in literati paintings17, as a holistic Chinese traditional culture, are open to everyone. Therefore, both in terms of concepts and techniques, it has actually broken the gender division of literati painting in the historical context and has become a classical art that can be perceived and followed by both men and women. Inseparable from it is the overall worldview and outlook on life contained in this ink and wash language.

It is not difficult to imagine that when Zhang Yanzi looked at Tao Yuanming’s stringless qin (Chinese lute), her intuitive reaction would not be looking at the work of a male artist, but rather the work of a “man” (or even a “god”). —In fact, perhaps only by understanding the subject of literati painting as a “person” and also understanding oneself as a “person” can one achieve this “connection” that transcends time and space in one’s own “individual” life.

Looking back at “gender” from the perspective of a holistic “person”, one will find that “she” is neither a “subject” nor an “object”, and does not exist as a “thing” or “non-thing”. As Zhang Yanzi said, “she” is just a certain (personality/female) “experience”.

How does a female artist use her “female experience” in her creation? —It is my understanding, it is just a kind of “convenience”, that is, using gender as a “convenience”. Just because one happens to have this experience, one can use it skillfully, which varies from person to person, time to time, and place to place; therefore, it is difficult to abstract and generalize it into a “method”18.

Fragments 05, Mixed media, Dimension variable, 2024

Zhang Yanzi once made an analogy about this experience: ancient scholars would also paint the various cultural relics on their desks; now, she depicts the fruits and medicines on her desk—it’s the same thing, “Painting capsules is just my eyes returning to my life19.

Once you focus your eyes on your own life experience, the so-called “framework of Chinese painting” will disappear in an instant, “suddenly I feel so free”, which is natural. From then on, Zhang Yanzi’s works have many “convenient and skillful” things, which I will not elaborate on here.

Using gender as a “convenience” is also applicable to male artists who create works based on individual experience. Perhaps because of this, the subtle differences between “experiences” in the works often bring about a shocking effect, so that Xu Lei, an artist who is also good at ink painting, said when evaluating Zhang Yanzi’s “The Remedy”:

Her new work can be said to be a sharp point. In terms of its surprising subject matter, it is already an unprecedented new reference in the history of Chinese Painting Encyclopedia. 20

Fragments 06, Mixed media, Dimension variable, 2024

“Dharmakāya Appearance” Beyond Gender

When I realized that “she” was just a “convenience” for Zhang Yanzi to reach her creation, the heavy trance disappeared.

From then on, the viewer’s eyes will no longer stay on those seemingly clear “female appearances”: lips in “Flowing Light” (2024), uterus in “Beginning of Spring” (2022), menstruation in “Awakening of Insects” (2022), special-shaped hospital beds in “Sanctuary” (2016)... but calmly pass through various “appearances” and see other things.

—I seemed to see the “Dharmakāya appearance”.

As we all know, the “Dharmakāya appearance” is a transcendental realm beyond genders and can be reached by both men and women. At the exhibition, I vaguely sensed Zhang Yanzi’s wish: even if one wants to explore female artists or feminism, one should not focus on “gender” but should transcend it—because the secular world in which men and women live is not the entire “life world”: beyond the body, there is the spirit; beyond the spirit, there is “inward transcendence.”

While our artists are already using “transcendental spirits to inquire about worldly affairs”21, our critics seem to have not yet analyzed: Is there a theory that can be adapted to explain or criticize them?

Encounter (detail), Hollow scroll and mixed media, 320×90cm, 2022-2024

Encounter (detail), Hollow scroll and mixed media, 320×90cm, 2022-2024 Encounter 03 (detail), Hollow scroll and mixed media, 2022-2024

Encounter 03 (detail), Hollow scroll and mixed media, 2022-2024

Walking out of the “Abyss”

In 1994, the 7th issue of Jiangsu Art Monthly (now Art Monthly) published an art criticism article by Xu Hong entitled “Walking out of the abyss—a letter to female artists and female critics”. This was regarded as “the first appearance of the voice of a female critic... it is tantamount to a feminist criticism manifesto” 22.

What is interesting is that this manifesto was written to both female artists and female critics. This means that the “criticism” subjects of this article, those who should walk out of the “abyss”, are not only female artists, but also female critics—both of them are like “comrades-in-arms” or “fellow sufferers” fighting side by side. At the end of the article, it is declared:

People should realize that modern art without clear and conscious feminist art is not thorough modern art.23

Since then, the comments on Chinese female artists seem to always be accompanied by the changes in Western feminist thought and various applications. Such as “sex”, “motherhood”, “patriarchy”, Freud’s “psychoanalysis”, Beauvoir’s “other”; in postmodern period, various propositions have emerged in an endless stream, and it is unknown how long the popular “eco-feminism” can last... It seems that without these concepts, our critics do not know how to interpret these works created by women.

Chasing the Wind A Thousand Miles Away (detail), Album of painting, 51.5×1191.5cm

Chasing the Wind A Thousand Miles Away (detail), Album of painting, 51.5×1191.5cm

However, it should be noted that the “women’s movement” in China has a very different history from the women’s movements in the West, and can be used as differentiated empirical materials to contribute to theoretical research. However, feminist research in the Western academic community rarely takes the former as an object of discussion. This means that the feminist movement and thought based on Western social experience and ideology should be “doubted” for the explanatory power of Chinese women’s “experience and mentality” 24.

In other words, before adopting these feminist concepts and theories to interpret Chinese female artists and their works, we must be cautious: do not let the artist’s “individual” unique life experience become a theoretical footnote to the “other” 25. On the contrary, perhaps only by returning to the “individual experience” of each creator and starting from his or her inner perspective can we achieve a “comprehension” of criticism; the academic research based on this basis can dialogue with and reflect on currently popular concepts and theories.

Therefore, I think that empirical research—starting from “people” and their “overall social facts” may be a path of art criticism that can be considered.

In this regard, isn’t the so-called “feminism” just another “abyss” that needs to be escaped from?

About the Author

He Beili is an associate professor at the School of Experimental Art and Sci-Tech Art of the Central Academy of Fine Arts. She graduated from Xi’an Jiaotong University with a double bachelor’s degree in Chinese Language and Literature as well as Management. In 2008, she studied social anthropology at the Department of Sociology of Peking University, conducted field research at Samye Monastery in Shannan, Tibet, China, and received a doctorate degree for her research on Tibetan anthropology. In 2014, she conducted postdoctoral research at the School of Ethnic and Social Sciences of Minzu University of China, conducted field research at Hongke Temple in Golog, Qinghai, and completed her postdoctoral research in 2017. In 2019, she joined the Central Academy of Fine Arts and taught at the School of Experimental Art and Sci-Tech Art, and has been teaching since then. She teaches courses such as “Field Research: Oral History”, “Image Anthropology”, and “Thesis Writing”.

She has published the diary ethnography No Beginning and No End: Kora (a transliteration from the Tibetan word kor) (2020, Tibetan Ancient Books Publishing House in Tibet), and the academic monograph Ritual Space and Civilization’s Cosmology—Anthropological Research on Samye Monastery (2022, Tibetan Ancient Books Publishing House in Tibet).

This article was originally published in the 7th issue of Art Monthly in 2024.

Notes:

1. In the context of contemporary Chinese art, women’s art and feminist criticism actually began in the 1990s.

2. Lin Shuchuan: “Foreword”, “INDIVISIBLE: Zhang Yanzi’s Solo Exhibition”, Art Museum of Nanjing University of the Arts, 2024.

3. From October 4 to October 28, 2023, Zhang Yanzi’s solo exhibition “The Dangerous Balance” was held at Gallery of Feminism founded by Antoinette Fouque (ESPACE DES FEMMES-Antoinette Fouque) by Women’s Alliance for Democracyin Paris.

4. This passage was a comment by curator Qin Dandan, published on the WeChat public account of Village One Art Gallery (Qin Dandan is one of the founders), titled: Zhang Yanzi | Wonderland, November 14, 2020.

5. Rosemarie Putnam Tong: Feminist Thought A More comprehensive Introduction, translated by Ai Xiaoming et al., Central China Normal University Press, 2002.

6. Lionello Venturi: History of Art Criticism, translated by Shao Hong, pp. 32-33, Commercial Press, 2020.

7. Gregory Battcock: “Introduction”, in Lionello Venturi: History of Art Criticism, translated by Shao Hong, p. 5, The Commercial Press, 2020.

8. Li Xiaojiang: Female Utopia: Twenty Lectures on Chinese Women/Gender Studies, pp. 3-30, Social Sciences Academic Press, 2016.

9. Ibid., pp. 23-24.

10. “Yi Guan Headline | Zhang Yanzi: Cruelty is also poetic, and pain is also worth praising”, published on WeChat public account “Yi Guan”, October 19, 2023.

11. Zhang Yanzi, “Feminism is an awakening beyond gender consciousness”, published in Art Market, No. 6, 2012, pp. 90-91.

12. Borrowing the concept of “total social facts” from Marcel Mauss (1872-1950). Marcel Mauss: THE GIFT: Forms and Functions of Exchange in Archaic Societies, translated by Ji Zhe, Shanghai Century Publishing (Group), 2005.

13. Borrowing Buddhist terminology, it refers to teaching students in a flexible and skillful way so that they can understand the true meaning of Buddhism. The Vimalakirti Sutra states: “Use the power of convenience to explain and show the truth to all living beings.” The Platform Sutra states: “If you want to convert others, you must have convenience.”

14. Pei Gang and Zhang Yanzi: “Dialogue | Zhang Yanzi Heterogeneous Landscapes”, published on the WeChat public account “Artron Art Network”, March 29, 2024.

15. Tao Yongbai: “Introduction”, in Tao Yongbai and Li Xi: The Lost History: A History of Chinese Women’s Paintings, pp. 1-10, Hunan Fine Arts Publishing House, 1999.

16. Borrowing the concept of “parallel structure” from Marshall Sahlins (1930-2021) to illustrate the “relationship” between structure (the ink and wash tradition of literati painting) and event (the individual creation of the artist). Marshall Sahlins: “Introduction” to The Island of History, translated by Lan Daju, Zhang Hongming, Huang Xiangchun and Liu Yonghua, pp. 10-12, Shanghai People’s Publishing House, 2003.

17. Qu Jingdong (ed.), Chinese Civilization and the World of Landscape (Volume 1), SDX Joint Publishing Company, 2021.

18. Xiang Biao and Wu Qi: Using Myself as a Method: A Conversation with Xiang Biao, Shanghai Literature and Art Publishing House, 2020.

19. Zhang Yanzi and Hu Xiaolan: “Zhang Yanzi: Separation and Breathing, Pain and Healing | Observation and Interview on the ‘CAFAM Biennale’”, published on the official website of the CAFA Art Museum, December 5, 2016.

20. Xu Lei: “The Remedy: Zhang Yanzi’s Heart Sutra on Paper”, published in Art Research, No. 3, 2019, pp. 8-9.

21. Yu Yingshi: A Study on the History of Chinese Intellectuals, Yu Yingshi: Collected Works of Yu Yingshi, Volume 4, A Study on the History of Chinese Intellectuals, pp. 1-25, Guangxi Normal University Press, 2004.

22. Later renamed “Out of the Abyss: My Feminist Criticism” and included in the collection. Jia Fangzhou, ed., The Age of Criticism: A Collection of Chinese Art Criticism in the Late 20th Century, Vol. 1, “Preface”, p. 17, Guangxi Fine Arts Publishing House, 2007; Xu Hong, “Feminist Art Criticism in the Context of Contemporary Chinese Culture”, Mei Yuan, No. 3, 2007, pp. 19-21.

23. Xu Hong, “Out of the Abyss: My View on Feminist Criticism”, in Jia Fangzhou, ed., The Age of Criticism: A Collection of Chinese Art Criticism in the Late 20th Century, Vol. 3, pp. 63-65, Guangxi Fine Arts Publishing House, 2007.

24. Wang Mingming, “Preface”, Experience and Mentality, p. 1, Guangxi Normal University Press, 2007.

25. Wang Mingming, The West as the Other: On the Genealogy and Significance of China’s “Western Studies”, World Book Publishing Company, 2007.