By CAROL VOGEL FEB. 14, 2014/The New York Times

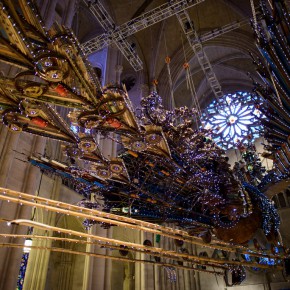

On a recent wintry afternoon, a team of eight was putting the final touches on a pair of monumental birds that had just been hung in the majestic nave of the Cathedral Church of St. John the Divine in Morningside Heights. As these phoenixes hovered some 20 feet above, their tiny, twinkling lights illuminated an array of unexpected materials: feathers fashioned from impeccably layered shovels; crowns made of weathered hard hats; heads created from jackhammers; and birds’ bodies sculpted from other salvaged construction debris, including pliers, saws, screwdrivers, plastic accordion tubing and drills.

In the middle of it all was Xu Bing, the internationally acclaimed Chinese artist, dressed in a black T-shirt and jeans, with a black-and-white scarf wrapped fashionably around his neck and his signature round glasses perched on his nose. When asked about the birds’ placement, one in front of the other inside the massive Gothic-style church, he impishly replied through Jesse Robert Coffino, director of his New York studio, who was acting as interpreter, “The girl is closer to God.”

Both Feng, the male, and Huang, the female, faced the decoratively carved bronze doors, as if poised to take flight in the middle of the night. “If they faced toward the church,” referring to the altar, Mr. Xu explained, “it would have seemed too religious.”

Throughout China’s history, every dynasty has had its form of phoenixes. Representing luck, unity, power and prosperity, these mythological birds have, for the most part, been benevolent, gentle creatures. But this pair, fashioned from the materials of commercial development, reflect the grimmer and grittier face of China today.

“They bear countless scars,” Mr. Xu explained, having “lived through great hardship, but still have self-respect. In general, the phoenix expresses unrealized hopes and dreams.”

A 59-year-old Conceptual artist who works in a variety of mediums — calligraphy, ink painting and installations — and who received a so-called genius grant from the MacArthur Foundation in 1999, Mr. Xu has seen firsthand China’s many transformations. During the Cultural Revolution, his father, a professor of history at Peking University, was banished from his position, and Mr. Xu was sent to the countryside. Some 13 years later, he moved to the United States, eventually settling in New York.

In 2008 he returned to China, after having been offered the prestigious job of vice president of the state-runCentral Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing, China’s top art school.

He still keeps a toe in New York, a city he said he considers a home after living in the East Village for six years, and the Williamsburg section of Brooklyn for 12. On a recent weeklong trip here to oversee the installation of the phoenixes, which he described as “the king of birds,” Mr. Xu spoke about them.

The project started in 2008, when he was asked to create a sculpture for a glass atrium at the base of a new building designed by the architect Cesar Pelli for the World Financial Center in Beijing’s central business district.

“When I first visited the building site, I had a sense of shock,” Mr. Xu recalled in an interview at a coffee shop near St. John the Divine. “It was impossible to imagine that with all the modern technology today, the building was constructed with such low-tech methods.”

The poor working conditions for the migrant laborers who were building such luxury towers, he said, “made my skin quiver.” Mr. Xu had such a violent reaction to what he saw that he decided to make the phoenixes rise, as it were, out of debris and workers’ tools that he salvaged from the construction site.

That was just a few months before the financial crisis of 2008. It was also when there was a government ban on all trucking and construction to ensure cleaner air during the Beijing Olympics. The building’s developers, afraid that the birds carried a message about waste, asked Mr. Xu if they could be gussied up, perhaps with a crystalline exterior.

He declined, and, in the end, the developers rejected his birds. But Mr. Xu was determined to forge ahead. He had them constructed at a factory on the outskirts of Beijing, where they were to have taken take four months to complete. Instead, the process took two years, with Mr. Xu working from drawings, models and computer-generated diagrams. While they may appear to have the naïve quality of Chinese folk art, every inch — from beak to tail feather — was carefully considered.

Their appearance in New York is not their first public outing. They were on view twice in Asia, in front of the Today Art Museum in Beijing and at the Shanghai World Expo in 2010.

Judith Goldman, a writer and independent curator, saw the phoenixes at the factory in Beijing and decided they should be shown in the United States. “Xu Bing’s junkyard creatures resonate with many meanings, and I thought no place would be more fitting than the cathedral’s great nave,” she said, and she contacted the cathedral.

The Very Rev. Dr. James A. Kowalski, the dean of St. John the Divine, said that throughout its history, the church has used art, performances and talks to “create a discourse.” He called Mr. Xu “a global citizen who sees from this debris the human condition.”

“This beautiful, even sacred installation has transformational powers,” Dean Kowlaski went on. “This is not just a critique about laborers in China, it is about a subject that affects us all. It’s about fair pay and human wages for all people.”

Before coming to New York, the birds made a stop at the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art in North Adams, where they were on view in a converted factory building for nearly a year, starting in 2012.

When they were at that museum, “what I found so interesting was that it almost seemed as though they were returning to their ancestral home,” Mr. Xu said, explaining that North Adams had been a 19th-century industrial center that fell victim to economic hardship.

The phoenixes arrived in New York late last month on nine flatbed trucks. Together weighing over 12 tons and measuring 90 and 100 feet long, they required over 30 hoists and 140 feet of trussing to raise them so that they appear to be soaring through the cathedral. They will be on view for about a year.

“The birds have different meanings in different places,” Mr. Xu said. “This cathedral is monumental and very lofty, and the phoenixes now have a sacred quality.”

A version of this article appears in print on February 15, 2014, on page C1 of theNew York edition with the headline: Phoenixes Rise in China and Float in New York.Courtesy of the author and the New York Times, Photo Courtesy of artist and Andrew Burton/Getty Images.