上世纪90年代,在多元文化主义甚嚣尘上之际,后殖民理论却揭示了存在于“多元文化主义”之中的本质主义倾向。例如霍米·巴巴(Homi K. Bhabha)提出:多元文化主义导源于自由主义意识形态,其特征是通过文化宽容的姿态,将他者固着在由西方主流文化所预设的位置之上,其实质仍然是一种整体论。[1]最早将非西方艺术家带入国际视野中的“大地魔术师”展(1989年)在这方面提供了一个鲜活的标本,并因而广受争议。随着这类批判的逐步深化与广为传播,1990年代下半叶之后,在1980年代曾经十分流行的那种以文化符号为依托、带有人类学印记的艺术创作方式,逐渐淡出人们的视野,无论是艺术家还是策展人,都更加注重文化之异源性和非决定性,注重不同文化之间的平等对话,注重立足于本社群的当下现实,并试图在这种新的基础上实现与国际社会之间的对话与协商。

然而,这些努力是否真的改变了“多元文化主义”的旧有架构?今天,奔走于各类国际展览的非西方艺术家,究竟如何参与了国际当代艺术?本文将以三位著名的当代非西方艺术家玛丽娜·阿布拉莫维奇(Marina Abramović)徐冰(Xu Bing)艾尔·安纳祖(El Anatsui)为例,分析当代“他者”是如何以更隐蔽、更为结构性的方式,参与了以西方文化逻辑为基础的当代国际艺术乌托邦的建构的。

一

前南斯拉夫行为艺术家阿布拉莫维奇有着双重的身份:她来自一个前社会主义国家,但就其文化根基而言,却是隶属于基督教传统的塞尔维亚人。这一点对于阿布拉莫维奇的创作及接受来说无疑是重要的,不过,阿布拉莫维奇的作品中很少会出现直接的政治指涉,也极少用文化符号来亮明自己的身份。尽管她的作品中也存在着一些政治隐喻,但她的价值、她被接受的关键,却并不在这里。

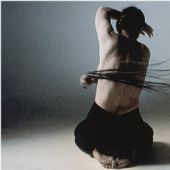

回顾阿布拉莫维奇漫长的行为艺术创作历程,我们会发现她的作品有几个重要的特点:第一、简洁,几乎总是用最直接的方式,直指身体和精神的极限;第二、大量地使用隐喻,具有仪式感;第三,对抗性,反复地诉诸二元对立。

简洁性从一开始就伴随着阿布拉莫维奇。1970年代初,她创作了一批赖以成名的作品:《节奏》系列、《释放》系列、《空间中的关系》等,无一不具有极其显著的简洁性,以一种不证自明、无法绕行、无需释义的方式,直指人类身体与精神之极限。这种直指核心的简洁性,带给了她的艺术某种原初力量,而这经常被看做她的魅力所在。

实际上,我们应该看到,这里所显露出来的是某种流行于20世纪中叶的总体趋势,即艺术本体之纯化。这个趋势在格林伯格(Clement Greenberg)的叙述中被阐释得淋漓尽致,因而总是与绘画之不断驱逐外来影响、实现自我意识的过程联系在一起。但这场运动并未局限在某个艺术门类之内,相反,在视觉艺术、音乐、舞蹈、戏剧等各大艺术门类中,都出现了回归本门类艺术本体的纯化运动。而回溯这场运动之根源,我们至少可以追溯到1920年代的演员及剧作家、剧场理论家安托南·阿尔托(Antonin Artaud)身上去。

阿尔托在《残酷戏剧:戏剧及其重影》中提出,要对戏剧进行纯化,消解古典戏剧中存在的文字中心和心理分析传统,最终消解西方文化中的逻各斯中心主义,让戏剧回归至戏剧之“前夜”,以剧场、以身体为核心。[2]但又绝不要依靠演员的瞬间感受和爆发,而是要让整个戏剧有所控制地展开。为此,他引入了象形文字和东方宗教剧作为类比,认为戏剧表达应具有象形文字的准确性、直接性、与神圣之物的相关性,应该以某种类似于弗洛伊德的“梦”的方式来运作,但这梦又绝不能委身于分析师的躺椅。他将“残酷”二字解释为必要性,认为它与命运相关。

阿尔托几乎从未实现过自己的戏剧理想,在他身后究竟有谁曾经实现了这个理想,这也是未决之事。倒是“残酷”二字,经常被作字面的理解,因而衍生了一整批以血腥为诉求点的作品。但无疑,阿尔托为戏剧之走向戏剧自我意识提供了强大的推动力。阿尔托的影响,在1960-70年代先后在美国和欧洲全面复兴,并带来了剧本的边缘化,戏剧试图脱离文本而独立。而根据苏珊·桑塔格(Susan Sontag)的观察,与同一时期的戏剧相比,倒是偶发艺术更为接近阿尔托的理念。[3]这类艺术充分地使用了身体,并且彻底排斥了文本。[4]

从这个角度来看,行为艺术大量地繁荣于1970年代,且大量地诉诸极限、乃至血腥,这并不是偶然的。而阿布拉莫维奇在这个时期的创作,即从属于这条主线。实际上,与大多数同时期的行为艺术家相比,阿布拉莫维奇在“极限”方面并非十分突出,毋宁说,她更为突出的是其简洁性和必要性,就此意义上,她比任何人都要接近阿尔托。

但是,对阿布拉莫维奇的阅读还有另外一个维度,即隐喻与仪式感,这一点更为复杂。

在隐喻的层面上,解读阿布拉莫维奇并不难。从早期的《节奏5》,到让她声名大噪的《托马斯的嘴唇》,再到《巴尔干巴洛克》或者《海上夜航》,她所使用的隐喻大都有着清晰的语义。她经常使用的那些符号,例如五角星、蜂蜜、鞭子、骨骼等,都有着直接的宗教和政治指向,我们甚至可以为她归纳出一套类似于博伊斯(Joseph Beuys)的隐喻体系,让她的作品在某种图像学的意义上被系统地解读。此外,她也很善于使用原型,1985年制作的《长城》影片即说明了这一点。

但这仅仅是表象。阿布拉莫维奇的复杂之处,并不在于她所使用的隐喻,而在于她将这些隐喻组合、并诉诸某个文化体系的方式。大体上来说,阿布拉莫维奇的隐喻归属于三个类别:政治、基督教、原始宗教。而她的全部复杂性,即来自于这三种类别在20世纪西方文化语境中的相互纠结。

后启蒙时代的西方经历了去神化的过程,基督教在教会、信仰团体和社区仍然发挥着相应的作用,在文化中却不再是主流。但我们很容易观察到,在当代西方艺术中,基督教依然是一个强大的存在,体现为相互矛盾的两个方面:一方面,它经常被当作陈腔滥调、霸权之终极叙事者而受到戏拟和嘲弄;另一方面,它又充当着思想和精神的最后依托,提供着价值、理念、文化概念。在行为艺术的领域里,赫尔曼·尼斯(Hermann Nitsch)的创作在这方面具有典型性,但并不细致,而阿布拉莫维奇则抓住了更为核心的东西。她所使用的,是基督教最关键的概念之一“受难”,这是救赎史的高潮,也是转化的开端,在后世教会和民间的宗教实践中,受难始终是最具有凝聚力和号召力的中心意象,在整个基督教史上一再重现。它的极端表现是“五伤”圣人的涌现和13世纪中叶的鞭笞派大游行。通过自我鞭笞、吃蜂蜜、净化枯骨、跪拜、上十字架、任公众摆布等行为,阿布拉莫维奇实际上接管了基督教的基本内容。而她的接管之所以成功,正是因为她从未直接诉诸宗教,而总是通过被转化和内化了、去神化的、拥有现代形态的仪式,来实现隐秘的移交。从而同时实现了后基督教的西方文化对自身之文化基因的排斥与怀乡。

不过,这仅仅是其中的一个层面而已,我们也许应该回想一下:阿尔托在1960-70年代的复兴,阿布拉莫维奇及一批行为艺术家在1970年代的繁盛,在时间上都与一个重要的政治和文化运动偶合——五月风暴。当然,五月风暴是多维的,但它有一个清晰的形式层面:仪式感。人们已经就五月风暴前后数十年间欧洲青年文化中所出现的新特点做过大量的研究,斯图尔特·霍尔(Stuart Hall)通过对一部著作的命名对此做了精辟的概括:《通过仪式抵抗》。[5]在那个时期的青年文化中,发型、衣着、犯罪、性泛滥、麻醉药、神秘宗教等,都是抵抗现有的西方资本主义文化的某种方式,这就为我们理解阿布拉莫维奇作品中的某些仪式提供基础:例如《节奏2》中吞服的精神类药物、总是在路上的老吉普车、《海上夜航》中的飞去来和金矿等。[6]如果说她的作品的确有政治意味,那么,这种意味大都是在这个层面上来进行的,并因此比那些符号化、图像化的东西,更能触动西方文化的深层。

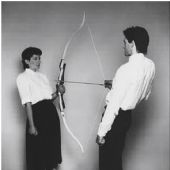

最后一点是关于她艺术中持续存在的对抗性。我们应该开宗明义地提出:这是对二元论的复现,也是对恐惧政治的复现。在阿布拉莫维奇的作品中,非但与乌雷(Ulay)合作的那些总是以对抗的形式出现,即使在她独立完成的作品中,与某种权力或力量的对抗也是重要的主题。当然,我们可以将此理解为对某类“关系”的探讨,但其中的二元论色彩、所潜存的价值判断,却是无法忽略的。这就使得阿布拉莫维奇的作品尽管拥有复杂的隐喻系统和文化语境,却也避免不了明确的语义。

作为一场文化运动,五月风暴最突出的成果是让消解二元论的论调占了上风,经过各种身份政治斗争和话语争鸣,多元化、多样性、差异性逐渐成为政治正确性的内容。但这无法回避自由世界需要借助二元论来维系其整体性、其在价值谱系中的崇高地位,这是当代西方文化的吊诡之处。包括齐泽克(Slavoj Žižek)在内的一些知识分子早就观察到:今日西方世界的正常运转,有赖于对某些外部力量的妖魔化,需要依靠恐惧政治来维系内部之凝聚。这个对象在历史上是可变的,今天主要化身为穆斯林,而它的原型则是不变的,都是一个被指认、被想象的他者,被非人化的恐惧对象。到今天,在全世界面临日益紧迫的经济和政治危机的时刻,这一点就看得更清楚了。

当然,这个事实无法得到直接了当地的认可。在当代艺术界,强调多元化、多样性、差异性的论调仍是主流,这是政治正确性所需要的。而阿布拉莫维奇的直截了当、但又语焉不详的作品,却提供一个被内在地需求着、但又不能被言说的对抗性结构。在这个意义上,她的作品无异于提供了一个集体宣泄的空间。

在这个节点上,我们可以提出两件极为重要的作品作为总结:《海上夜航》和《艺术家在现场》。这两件作品拥有相似的结构,对抗性、仪式感、语言的纯化,凝缩为一个最为简单、直接的对视行为。但不同的是,前者是阿布拉莫维奇与乌雷之间的对视,并用了一些来自澳洲土著的原始宗教用品作为道具,其语义和语境都是相对明确的;而后者,尽管也是诉诸四目之间的对视,却只有阿布拉莫维奇一个人,面对所有可能坐到她面前的人,道具也简化到只剩一张桌子和两把椅子。通过这样的变化,《艺术家在现场》引入了另外一个至关重要的维度。

在这里,我们又要回到阿尔托。阿尔托曾经是一位超现实主义者,也是最早用弗洛伊德(Sigmund Freud)的语调发言的艺术家之一。尽管他敏锐地看出精神分析活动中潜存着回到逻各斯的风险,但他却认为精神分析的结构是残酷戏剧所必须的:梦的结构、象征的结构。关于被拉康(Jacques Lacan)复兴的精神分析学在五月风暴之后的重要性,无需多言,有人甚至称之为一个“精神分析化”的世界。影响所及,非但拉康渗透到诸多理论家的思想中,公众也学会了以精神分析的方式去自我认知。可以说,《艺术家在现场》用一个极其简洁的装置“对视”,架构起了一台庞大的精神分析机器,它既带有东方宗教的简洁与神秘(阿尔托所向往的),也带有对抗性、仪式感,同时溯源了基督教的传统(回想一下乔托(Giotto)壁画中基督与犹大、圣母与以利沙伯的对视),而这一切,皆被融合到一件简洁的、十分当代的作品中去了。不能不说,这是阿布拉莫维奇的集大成之作。

二

以某种巧妙的方式,将被隐蔽、又被需求着的二元论结构引入当代艺术中来,这并不是阿布拉莫维奇的专利,在这个序列中,我们仍然可以发现其他艺术家,比如中国艺术家徐冰。

徐冰是中国当代最重要的艺术家之一,也是最有国际影响力的非西方艺术家之一。从早年的《天书》到《新英文字母》,再到《地书》和近期的《蜻蜓之眼》,徐冰最好的作品,几乎都在处理语言碎片,人们常常论及他和德里达的关联,这无疑是理解他的一个重要框架。徐冰的作品十分多变,但这并不是指他所使用的材质或创作方法,而是指他的创作语境。总体而言,徐冰的作品可以大致分为三类:一是处理语言碎片的这部分;二是创作于1990年代,带有明显的文化符号特征、以处理东西方文化之关系为旨归的作品,它们从属于那个时代世界范围内的“后殖民艺术”大潮。

第三类则很难归类,载体、题材都不相同,但其间也存在着重要的关联性,体现为:创作时间的相似性(几乎都创作于1990年代末以后,彼时徐冰已经是一位具有国际声誉的重要艺术家)、创作背景的相似性(大都是定制作品)、都动用了较大规模的资源、都是以国际社会为主要诉求对象。这似乎说明了这类作品是与徐冰作为一个成功的“国际艺术家”的身份密切关联在一起的,实际上,这类作品的内在的共同之处就在于它们以结构性的方式贴合于国际当代艺术主流,并以十分高超的手法,同时满足了尊重文化差异/维护现有的新殖民主义秩序这一对相互矛盾的基本需求。是否使用“文化符号”,这只是一个次要的技术性问题,更为重要的是通过对呈现什么、呈现为何的一次次选择,守护着自由世界的边界,将我/他这对基本的两分法,呈现于一种无差别的表象之中,但与此同时,这种呈现又应该标识出二者之间的根本差别。

以此为框架,我们便看到了徐冰“第三类”作品的整体性。和阿布拉莫维奇不同,徐冰从未建构起一套牢固的、系统性的哲学,以此进入当代艺术和文化的精神肌理。相反,他的选择看上去是松散的,常常让人们觉得这些作品之间缺乏相似性,但实际上,对这些作品做一个回顾便不难发现,他正是通过对呈现什么、如何呈现的选择,反复确认了既有的游戏规则的合法性。

如果说阿布拉莫维奇的动人之处在于她以富有冲击力的手法再现了二元论,并因而充当了某种疗愈机制的话,那么,徐冰的能力恰恰在于处理这类二元论的暧昧性。在这方面,2004年的《何处惹尘埃》是一个很好的案例。徐冰用一种东方禅机式的发问,介入了“9·11”这个世纪初最受关注的政治事件。这件作品之所以有趣,首先在于:事件本身的坚硬的意义内核与徐冰悬置这个意义的意图之间形成了强烈对比。关于“9·11”与恐惧政治之间的关系,及其对此后世界秩序的影响,人们已经谈得很多。齐泽克特别智慧地指出了它和好莱坞灾难片之间的内在关联,[7]这也就表明了,在对这个事件的反复表述中存在着一种原型化的企图,但它不能被直接陈述出来,否则原型化本身就会失败,抛弃了自由、宽容、平等的“我们”将和“他们”没有差别。

通过悬置一个不可能被悬置的意义内核,徐冰实际上摆出了一个空洞的姿态。这是绝妙的。因为保障“9·11”在权力谱系中之优越性的关键,仅仅在于维护它的可见性,而所谓被夺权者,被夺去的也正是这种可见性。[8]徐冰显然看到了这个最为根本的层面,他的空洞姿态既维护了这个事件的纯粹可见性,又没有采取任何立场,从而避开了一切可能的困境,而由于可见性本身就是立场,所以他实际上已经清晰地表明了立场。正由于意义内核是坚硬的,人们才可以去悬置它,这种悬置并不是真的悬置,但它毕竟是悬置。

《何处惹尘埃》还有另一个有趣之处:它建构了一个神话:徐冰将具有高度政治敏感性的尘埃做成女儿的玩偶,瞒天过海穿越海关。之所以说它是神话,是因为它采取了原型化的叙事手法:天真的女孩、愚蠢的国家机器、勇敢而智慧的英雄(艺术家)、具有重大历史意义的遗骸、最后还有大团圆的结局。套用齐泽克的说法:这个故事同样具有好莱坞大片的底色。

罗兰·巴特(Roland Barthes)说:神话是一种交流体系,它是一种信息。在神话中,重要的并不是被表述之物,而是表述的方式,这方式必定是历史性的。[9]也就是说:神话讲了什么故事,这并不重要,重要的是它所传递的信息、它所构建的关系、它与语境的相关性。实际上,徐冰的许多作品都是伴随着一则神话而进入公众视野的,而这些神话又大都使用了原型化的叙事手法。

在这方面的典范是《木林森计划》。这个项目最初是受国际资源保护机构等多家组织之托,在肯尼亚实施的。徐冰试图让肯尼亚孩子按照他所教授的方法画树,再通过一个由艺术品电子商务支撑的“自循环系统”将这些画卖出去,让资金回流到肯尼亚继续种树。这个项目的宗旨是保护肯尼亚的自然生态,让它不再依赖不可持续的外来捐助,而实现自我造血。很显然,这件作品的运转方式在市场上很难具有竞争力,难以在电子商务世界中独立、长久地运转,它的成败主要仰仗徐冰的个人影响力、以及围绕着这个项目的媒体攻势。

那么,这样一件作品,该如何吸引公众的目光?首先,它诉诸了一个绝对具有政治正确性的当代母题“环保”;其次,它诉诸了一个动人的神话。在这个神话中,徐冰标记出了两个基本意象:美丽而面临危机的肯尼亚、天真的肯尼亚孩子。他说,这些孩子几乎没有接触过艺术,对画具充满了敬畏感,面对外来的艺术家时,他们是羞涩而又满怀信任的,但是,他们所表现出来的巨大、淳朴的创造力,却震惊了艺术家。他还拿这些孩子跟中国孩子进行了对比,感慨说中国孩子是过度文明化的。这些表述中的原型化色彩是显而易见的,它让我们立即想起了高更(Paul Gauguin)笔下的塔西提。对于塔西提神话的殖民色彩,我们都很熟悉,通过浪漫、乃至悲情的笔触,它维护了野蛮/文明的两分法,反复确认了既定的世界秩序。

所以,徐冰的“自循环系统”所贩卖的,并不是肯尼亚孩子的画,而是西方世界对肯尼亚的殖民想象;西方公众为之付款的,也不是孩子的画,而是一种既定的世界秩序。从某种意义上来说,这种秩序早已包含在“环保”这个母题本身之中,与之相类似的还有“慈善”的母题,在那里,我们看到了思路和手法都十分类似的《赫尔辛基喜马拉雅的交换》。徐冰以如此巨大的热情投入的,并不是某一个项目,而是一个他必须予以确认和守卫的世界结构。

这让我们想起了《凤凰》,一件同样携带着神话的装置。谈论这件作品的中国符号、高能耗、缺乏形式感,都不得要领,如果与徐冰本人的阐释(探讨当下中国的劳资关系问题)相比,这些说法无论在理论功底、还是在对当下社会与艺术背景的观察方面,都相形见绌。这件作品的真正有趣之处,在于它的双面性。为了说明这个问题,我们将要提到另外一件中国当代艺术作品:艾未未在新泰特美术馆涡轮大厅的作品《1亿颗陶瓷瓜子》。《瓜子》远没有《凤凰》这样聪明,在它面世之时,人们马上辨识出了它对中国作为血汗工厂、低端制造业之国的形象的指认。但实际上,两件作品的结构是极其相似的:巨量劳动、巨大的资源消耗、清晰无疑的中国符号、以西方公众为主要诉求对象。只不过与《瓜子》的单向度不同,《凤凰》同时满足了国际社会对中国的(结构性)指认,和国内知识分子对于批判不合理社会现状的需求。

《凤凰》还有另外一个特点,是《瓜子》难以望其项背的,这便是围绕着它的一整套话语阐释体系。实际上,这也是徐冰许多作品的共同特征。一个由艺术家、批评家和理论家、诗人和文学家、文学评论家等构成的文本提供者群体,合力在作品周围建构起了一套包括大量访谈、研讨会记录、评论文章、相关书籍等出版物构成的阐释性文本体系。

阐释与作品的并行是当代艺术的特征之一,这个过程是由杜尚(Marcel Duchamp)推动的,又由他的阐释者们协助完成。杜尚之后,艺术失去自明性,需要文本的支撑,不论这种文本被指认为哲学、体制、还是契约,总之文本的存在成了艺术的内在需求,从而进入了艺术的“内部”。在很多情况下,文本的体量比艺术品本身更为庞大。但这并不像徐冰说的,是因为许多作品“看不懂”,而是因为阐释空间的大小已经成为判断作品之价值的重要标准。这也就解释了:为什么那些意义十分明确的作品,对阐释也有着同样的依赖性。事实上,围绕着作品的许多阐释,并没有把事情说得更清楚,而是让其更加模糊了。模糊并非没有意义,它起到了疏离的效果,扩张了作品的阐释空间,并因此提升了它。这样,我们就不难理解,为什么徐冰总是否认那些不言自明的东西,比如《烟草计划》中的他父亲的病历。

“阐释”还是一种霸权生产机制,它揭示了当代艺术中民主表象与霸权之间的矛盾并存。马库斯·米森(Markus Miessen)以一种激进的态度指出了十多年来盛行于政治与艺术项目中的“参与”式民主的霸权性质,认为参与的纯洁形象,恰恰掩盖了其游戏规则制定者的霸权属性。[10]实际上,在当代艺术中推动霸权的,不仅是被预设的游戏规则,还有日渐精巧化和专家化的阐释体系,它逐渐地排斥了门外汉的参与,将自己变成了一个封闭的领域,这既是由理论话语的日益复杂和快速更新所决定的,也是刻意引导的结果。阐释的空间打开了,阐释的可能性却封闭了。无限可能的幻景背后,却露出了霸权的单调背影。这不免让我们想起了卢梭,他曾说:自由是绝对的,但绝对的自由将使人做绝对正确的事,结果就是绝对的服从。[11]民主和霸权,可以是同一个事物的镜之双面。再前进一小步,我们便会看到,它是这个自由、民主、宽容的新殖民世界秩序的缩影。

三

《凤凰》、《瓜子》、《木林森计划》所勾画出的,是非西方地区在这个世界秩序中的基本位置,而这是需要通过政治、经济、文化、国际交流等各类话语的表述来反复加以确认的。顺着这个视野,我们又发现了另一位具有典型性的艺术家:来自西非的艾尔·安纳祖。

很显然,1990年代中期以后的安纳祖在艺术手法上的转变,是和一种越来越清晰的国际视野紧密关联在一起的。这种转变主要体现在三个方面:第一,越来越宏大的作品体量;第二,以瓶盖等金属制品为主的废弃物代替了原有的陶器与木材;第三,越来越多的匿名性参与,以及与之相关联的低技术、高能耗劳作模式。

安纳祖曾经反复提到过作品体量的问题,他认为作品的体量是与意义相关的,这无疑是正确的。事实上,对于许多当代艺术作品来说,体量本身就是意义的发生器。美国批评家唐纳德·库斯皮特(Donald Kuspit)在讨论1980年代的艺术时提出:1980年代艺术的特点在于一种歌剧性,其价值是由其宏大性和其姿态所界定的。[12]这种属性并不是1980年代的艺术所独有的,直到现在,仍然有不少批评家在谈论当代艺术的“宏大性”问题,并且对这种越来越追求景观化的艺术创作方式表示忧虑。库斯皮特的过人之处在于他一针见血地将这种对宏大性的诉求追溯到了瓦格纳(Wagner),并且指出:早在20世纪初,尼采(Friedrich Nietzsche)就已经对此提出了批判。

在《瓦格纳事件:1888年5月都灵通信》中,尼采尖锐地评论道:瓦格纳是一种疾病,他在音乐中猜度到刺激疲惫神经的手段,而这是最为“现代”的,他导向了一种对伟大、崇高、巨大、使大众激动的东西的诉求,而“成为巨大比成为美更容易”。[13]但瓦格纳并不仅仅在形式的层面上寻求宏大,他最终的诉求是一种思想上的宏大性:他寻求神圣性,震慑人心的音响效果、充满象征意味的姿态之网、充斥着陈词滥调的寓言,是他建构神圣性所使用的建筑材料。这种神圣性是大众所需要的,以其价值取向之不容质疑驱逐了思想,因而导向了霸权。所以尼采说:“瓦格纳这个演员乃是一个暴君,他的激情能推翻任何一种趣味,消除任何一种抵抗。”而他与“(第三)帝国”同时发迹,显然不是偶然的。[14]

今天我们把存在于当代艺术家中的“总体艺术”倾向追溯到瓦格纳,而只有在尼采所论述过的这个层面上,我们才有可能理解“总体艺术”的真正含义。它所指向的,显然不是一种形式或载体上的组合模式,而是一种由体量、形式、符号网络、思想框架所建构而成的霸权系统,在这个系统中,如今还要加上传播方式和阐释话语。当代艺术的景观化特征,因而应该被当作对霸权结构的模拟和确认。鲍里斯·格洛伊斯(Boris Groys)在一个略微不同的语境中指认出了这种霸权性。在讨论装置艺术及其空间性特征的时候,他提出:一旦观众进入艺术装置的空间,他也就进入了一种独裁的控制之中,必须服从艺术家所制定的法律。[15]

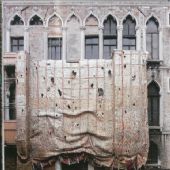

正是在这个意义上,我们才能理解安纳祖“将尺寸当做一种表达工具”[16]的意义。安纳祖本人的那些必须由体量来支撑的作品,也应该在这个语境中得到恰当的解读。1990年代,当安纳祖首度进入“国际艺术界”的时候,他深感自己的作品太小了,而当代艺术正在越来越大。在此后的20年间,他的主要工作之一便是不断地扩张自己的作品体量。瓶盖这个新的媒介提供了这种可能性,这是他转换媒介的原因之一。他自觉地投身于当代艺术系统,参与这种宏大景观的建设,[17]2007年威尼斯双年展上的《鲜活的&褪色的记忆》和《Dusasa》标志着他在这个领域内所取得的阶段性成果,如今,他不但是一个“局内人”,且已成为这个领域内的代表。

瓶盖这个媒介的使用同时带来了大量密集的低技术劳作,关于这一点,我们已经在《凤凰》那里提到过了.安纳祖反复地将它与非洲人的传统生产模式关联起来,这很难不让人做后殖民主义式的联想。但此媒介的使用有着比这个层面更为重要的意义。

瓶盖是一个废弃物。它还是一个现成品。作为城市生活的排泄物,它总能让人想起“消费社会”这样的母题,这就赋予了它天然的合法性。事实上,正是在转向瓶盖之后,安纳祖才收获了如今的声望,他自己很明白这一点,并且反复说:瓶盖是一个可以不断延伸的材料。但瓶盖的合法性不仅体现为它在拥有主流的价值取向,也体现为它在现代艺术史上拥有确定的位置。尽管安纳祖的评论者们还在不厌其烦地谈论着“安纳祖的作品是雕塑和绘画的跨界”,但谁都能看得出来,安纳祖的作品必须在现成品的框架中来理解。这也是杜尚的遗产。

有意思的是,安纳祖本人对这个问题的阐释采用了阿瑟·丹托(Arthur C. Danto)式的语汇和视角。可能是为了和通常的解释拉开一定的差距,安纳祖在一次访谈中特别提出:“我认为我所做的不是循环:我是将瓶盖“transform(转化)”成了别的东西。”[18]他所强调的转化,是在不改变瓶盖之性状的前提之下,实现某种隐喻性的变形,将一件废弃物转变成一件艺术作品,“uplift(提升)”这材料,将其举扬到艺术的位置上去。他还认为,这种变形是在罗布(lgbo)[19]宗教的意义上进行的,一件寻常的破陶器,经过这个过程,就进入了“精神维度”。[20]在这里,我们显然读出了丹托的身影。尽管安纳祖使用的词汇“transform”恰恰被丹托严格地区别于他自己所使用的更为明确的宗教语汇“transfiguration(变容)”,[21]但两人同样求助于宗教的解释,说明了安纳祖所说的“transform”的含义并不仅仅是丹托所界定的“形态变化”,而恰恰包含了“transfiguration”的全部宗教和隐喻意义:在不改变性状的前提下,对象发生了属性的转变。

因此,通过瓶盖,安纳祖全然地投身于西方现代美术史,而当代艺术界也积极地给予了他相应的回馈。当他说“1990年,我作为非洲艺术家参与了威尼斯双年展,而16年后,我仅作为艺术家而参与”,[22]他的判断大致是正确的。但他显然没有打算忽略自己的非洲背景,这一点也是正确的。细心的读者不难发现,在安纳祖对自己作品的阐释中充满了矛盾:一方面,他不断地联系到非洲本地的风俗、宗教、历史、现状,非洲殖民史,艺术家个人史等因素,将与非洲的关联性作为作品的阐释要素;另一方面,他又不断地否认自己的作品与非洲属性的任何直接关联。很显然,他不希望非洲符号、异域风情成为他作品的接受语境,但他同时也很清楚,这一部分也包含在国际主流艺术界对他的期待之中。[23]这一点特别清楚地体现在他对作品的命名中:他的几乎所有作品的标题,都是后加的,带有极强的阐释性,但与此同时,他又反复提醒他的观众,这些标题是可以忽略的。这并不矛盾,特别是我们早已习惯于矛盾之两面的同一性。因此,非洲的安纳祖正是国际的安纳祖,而国际的安纳祖并不具有非洲性,这个论断应该不会让人感到惊奇。

阿布拉莫维奇,徐冰,安纳祖,三个“他者”,以三种方式投身于国际当代艺术的建构,自觉地置身于西方现代美术史的脉络之中。在他们身上,呈现出当代非西方艺术家的一些典型特征,这些特征说明:奔走于国际展览的“他者”们并不具有他者性,他们属于“中心”,非其如此,他们便不太可能受到如此广泛的认可。[24]不过,他们的核心地位,却需要在一个边缘的位置上、通过对边缘性的某种含混的自我指认来确定,这种指认不可以清晰、但也不可以不清晰。不论我们向后殖民说过多少次再见,却欲罢还休地纠缠在它的结构之内。从某种角度来看,今日世界上的民族主义回潮也许并不是一个坏现象,至少,它可能会揭起文化差异的面纱,打破关于移民的神话,从而让我们看到,非但普世性是一个破产的乌托邦,混杂性也同样如此。

本文为第34届世界美术史大会演讲稿

发表于《世界美术》2016年第4期

English Version

The Other without Otherness:

On Three Contemporary Artists

By: Zhai Jing

In 1990s, some postcolonial theorists revealed the essentialism nature of the theories and practices of multiculturalism, which was widespread and influential then. Homi k. Bhabha proposed that multiculturalism is a liberal notion, which tends to recognize Other cultures in a pre-given frame that is inevitably Euro-centered, in the name of cultural diversity. Then, in the second half of 1990s, as cultural symbols that dominated the imagination of contemporary art in 1980s fading, people paid more attention to the everyday reality of their own society, and sought to communicate with the international society on this new basis.

Has this necessarily changed the old frame of multiculturalism? Which kind of role do the non-western artists play today? In this essay, I will focus on three contemporary artists – Marina Abramović, Xu Bing, and El Anatsui – and take them as example to discuss how do the Others take part in the construction of the Utopia of International Contemporary Art in a more subtle and more structural way.

1. Marina Abramović: Space of Collective Catharsis

Abramović has dual identities: she comes from a former socialist country Yugoslavia, while ethnically and culturally belongs to the Christian Serbs. This means a lot for her art creation and the reception of her works, but there is seldom direct political implication in her art works. Although she did have used some political metaphors, this was by no means her main attraction.

Generally speaking, Abramović’s works are characterized by three things: directness, use of metaphors, and confrontation.

The quality of directness was clearly visible in Abramović’s works from the very beginning of her career. Some early series of hers, such as Rhythm series and Freeing series, which were performed in early 1970s, touched the extreme of human body and spirit in a direct way. This kind of quality is characteristically Abramović’s, but is not exclusively used by her. In fact, it was derived from a trend of thought that was popular in the mid-20th century, which persuaded people to focus on the inherent qualities and potentials of a certain artistic medium. Clement Greenberg contributed a lot to this “medium specificity” idea, but this did not mean that the idea is valid only in painting. By contrast, the influence of it could be seen in many fields such as visual art, music, dance, drama, etc. As early as 1920s, Antonin Artaud proposed in his Theater of Cruelty that such elements as sound and gesture were more specific for drama than text and dialogue, which had been a tyrant over meaning for centuries. The development of drama, thus, according to Artuad, should focus on the body of actors and the space of theaters. In his interpretation, cruelty was a kind of necessity which was related to life itself. Artuad’s influence revived in America and then in Europe around 1960s and 1970s. Susan Sontag noticed that, compared with drama of that time, happening art had a closer affinity to Artaud’s idea. This kind of art resorted largely to the expressive potential of human body and deliberately rejected text. From this point of view, it was not a coincidence that performance art flourished in 1970s and sought to touch the extreme of body. In fact, what distinguished Abramović from other performance artists of her time was not “extreme” but the “directness” and “necessity” quality of her works. Therefore, it could be said that she was closer to Artuad’s idea than anyone else.

As her important works such as Rhythm 5, Lips of Thomas, Balkan Baroque and Nightsea Crossing suggested, Abramović tends to use metaphors in a straightforward way. This means that it would not be difficult for anybody to understand her works, but this does not mean that her works are generally simple. In fact, what makes her works sophisticated is the way she organizes these metaphors and makes them affect the contemporary western culture. Generally speaking, the metaphors she used could be captured in three categories: Christian metaphors, political metaphors, and metaphors related to primitive religions.

Christianity is still of importance for contemporary western world. On one side, it is the symbol of paternity, and thus the object of cultural critique; on the other side, it still feeds the western culture with notions and concepts. Among performance artists, Hermann Nitsch is famous for his use of Christian metaphors. But it is Abramović who has entered the heart of Christianity. To be precise, her metaphors were organized around “Suffering” which is a key concept of Christian faith. Her performance involved self-flagellation, purifying skeleton, worshiping, crucifixion, and subjecting herself to the masses. In this way, she literally took over the basic contents of Christian faith. And her success came from the fact that she had never resorted to the religion directly. Rather, she made it transformed and internalized, and adapted it in a modern way. Subtly, Abramović satisfied both the westerners’ rejection and their nostalgia of their own cultural gene.

As far as political metaphors are concerned, we should pay more attention to the context of Abramović’s art than her identity as a former Yugoslavian. The context is: the flourish of performance art in 1970s coincided with the May 1968. Being a political event, the May 1968 was noticeably featured by its ceremonial quality. The weapon that young people used to resist the capitalist society included not only self-made explosives and bricks, but also their unusual hairstyles and dresses, delinquency, abuse of sex and drug, mysterious religions, and so on. This is exactly the context in which we should understand the ceremonies in Abramović’s works, such as the psychotropics in Rhythm 2, the old jeep that was always on road, and the boomerang and gold mine in the Nightsea Crossing, etc. Actually, the political sense of her works is effective mainly on this level, so that they are much more touching than those works resorting to cultural symbols.

The sense of confrontation also features her works -- not only for those conducted with Ulay, but also for her solo works, -- revealing the dualistic nature of her art. This is especially interesting, because the deconstruction of dualism was one of the main achievements of the May 1968, and notions such as multiculturalism and cultural difference was dispersed as a result of this event. However, these historical phenomena work to conceal a simple fact that: the dualism is always needed, now as before, by the liberal western world. The liberal world needs a functional Other, in order to recognize its Self. But this should never be admitted. Abramović’s art works, direct as well as ambivalent, has offered the very needed yet unspeakable dualistic structure, and thus opened a space of collective catharsis.

2. Xu Bing: Guard the Liberal World

Abramović is by no means the only one who tries to bring the needed yet unspeakable dualism back into contemporary art. Xu Bing is equally success in doing so. In general, Xu Bing’s art works could be divided into three categories: the first series of his works deals mainly with language and words. The second series discusses the relationship between Eastern and Western culture. However, the works that are classified into the last series lack commonality in theme, style, and art media. Actually, they are different from each other, except for the fact that they share the similar time (produced after late 1990s), similar background (ordered and funded by certain institutes), and similar potential audience (international art world). This reminds us that they are related closely to Xu Bing’s identity as an “international contemporary artist”.

Actually, as we would see, what to be represented and how to represent is deliberately decided in these works, and they would help to guard the cultural boundary-line of the liberal western world. In this way, they satisfied the conflicting demands of respecting cultural difference while maintaining the neo-colonial world order at the same time.

Dualism could be found in many of Xu Bing’s works. But he is so skillful that this subtext could hardly be observed by the audience. Where Does the Dust Itself Collect? (2004) discussed the 9·11 from a Zen perspective. Frankly speaking, there was nothing new in this work. However, what makes us interested is the fact that: the symbolic meaning of this incident was clear, but Xu Bing endeavored to make that meaning suspended. Some scholars has proposed that the massive interpretation and propaganda around 9·11 should be acknowledged in the context of the politics of fear. Slavoj Žižek believed that the narrative strategy of 9·11 propaganda was parallel to that of Hollywood disaster films, which suggested that there existed an attempt of interpreting the incident in a stereotyped way. Again, this is unspeakable, or the stereotype will become invalid. However, there will be no difference between “we” and “they” if we lose our public image of freedom, tolerance and equality.

Suspending a meaning that could not be suspended, Xu Bing showed us a void gesture. This is excellent. The privilege of 9·11 in the value system relies on its visibility. On the contrary, what the dispossessed be deprived is this very visibility. Obviously, Xu Bing has observed this basic truth. His void gesture works to defend the sheer visibility of 9·11 without taking a stance. However, as the visibility itself equals a stance, Xu Bing did have showed his stance clearly. Let us put it this way: Xu Bing could try to suspend the meaning only when the meaning would never be suspended. This suspense might be a void gesture, but it is still suspense.

Historically speaking, stereotype worked as a basic narrative strategy in many colonial texts. And it works in a same way in many of Xu Bing’s works, among which the Forest Project (2008-undergoing) is a good example. In this project, Xu Bing makes Kenya children paint trees in the way he taught them and then sells their paintings via e-commerce. Once the paintings are sold, the earned money will be used to plant more trees in Kenya. Apparently, the project is ill-designed and can never run effectively in the long turn independently. Whether it will be successful or not relies completely on Xu Bing’s personal influence.

How can Xu Bing make such a work be appealing to the public? Firstly, he resorted to a popular modern motif “Environment Protection” that is politically correct. Then he created a romance which was starred by the gorgeous yet vulnerable Kenya and innocent Kenya children. He said: these children were so simple and imaginative that Chinese children seemed to be over-civilized compared with them. We could hardly ignore the sense of stereotype inherent in this narrative, which recalled Gauguin’s Tahiti immediately. There would be no need to recite the colonial nature of the Tahiti romance. We all know that it worked to maintain the pre-given world order by repeating and romanticizing the dualism of barbarism / civilization.

As we can see, what Xu Bing’s project sells are not Kenya children’s paintings but western public’s colonial imagination. Similarly, what the public pay for are not children’s paintings but the pre-given world order, which underlies such popular modern motives as “Environment Protection” and “Charity”. By the way, Xu Bing’s Helsinki Himalayan Exchange (1999) took “Charity” as its theme, and was similar to the Forest Project in many aspects. Therefore, what Xu Bing devoted himself to with great enthusiasm was not a ill-designed project, but a world order that he has no choice but to guard.

It is interesting that Xu Bing used to make his works, most of which are straightforward, complicated by enwrapping them with complex interpretation. Take Phoenix (2007-10) as an example. The whole process of funding, producing, and exhibiting this work was documented by a group of text providers, among whom are artists, art critics, poets, writers, etc. They endeavored to produce an interpretation system, which was composed by large amount of interviews, seminar documents, criticism articles, and books.

To some extent, contemporary art is featured by the intimate relationship between art works and interpretation, which is a legacy of Duchamp. In this post-Duchamp era, interpretation becomes part of the art work, and even tends to overwhelm the art work. Xu Bing once said that it was because contemporary art are confusing for the public. He is wrong after all. The reason lies in the fact that the possibility of interpretation becomes an important factor in deciding the value of art works. As a result, even those straightforward art works would resort to interpretation to make themselves seem to be more valuable. Interpretation does not necessarily help to reveal the significance of art works. Rather, it is equally possible that it would make people even more confused. However, this ambivalence of meaning is by no means meaningless. It works to create a sense of alienation and multiply the possibility of interpretation. From this perspective, we would understand Xu Bing, who used to deny those self-evident elements in his works such as his father’s medical records in the Tobacco Project (2000, Duke University, Durham).

Interpretation also works as a mechanism of hegemony. Markus Miessen tried to show us the hegemonic nature of “Public Participation” projects, which often promise us to be democratic, over the recent 10+ years. He believed that it was the innocent public image of “Participation” that helped to conceal the hegemonic nature of the rule of the game. And there is the interpretation, which tends to be more and more refined and professionalized. As the theories becoming increasingly complex and rapidly updated, the interpretation becomes an exclusive field for experts, and becomes hostile for outsiders. The possibility of interpretation is multiplied as well as minimized. What appears in the illusion of democracy is the shadow of hegemony.

3. El Anatsui: An Africa that Has Nothing to do with Africa

In mid 1990s, as El Anatsui got increasingly familiar with the international contemporary art, he decided to reform his artistic methods. His works became bigger and bigger since then. He replaced pottery and wood with metal materials such as bottle-tops. And the procedure of producing his works became labor-intensive, low-tech, and energy-consuming.

When Anatsui said that size is an expressive tool, he is completely right. It is the size that decides the significance of many contemporary art works. Kuspit proposed that “operatic” featured the 1980s art in America, and its value lied in its look of greatness. He pointed out with amazing insight that this tendency should be traced back to Wagner, and was criticized by Nietzsche.

In his Der Fall Wagner, Nietzsche commented that: Wagner was a sickness. He used the corruption of music as a means to excite weary nerves. He did not believe in beauty. Rather, he preferred the large-scale, the sublime, the gigantic, that which moves masses. Holiness, which was needed by the masses and which would shut the door of thoughts, was exactly what he wanted. Thus, Nietzsche said: “Wagner the actor is a tyrant, his pathos flings all taste, all resistance, to the winds.”, and “It is full of profound significance that the arrival of Wagner coincides in time with the arrival of the ‘Reich’.”

The contemporary interest for total-work-of-art should be traced back to Wagner. And it is from Nietzche’s perspective that we could acknowledge the significance of the total-work-of-art. It is not only a kind of artistic complex that is composed by series of different art media, styles, and forms, but also a hegemony mechanism that is sustained by grand size, gestures, and symbols. Therefore, the expanding size of contemporary art works should be regarded as the mimicry and confirmation of the hegemony.

In 1990s, when Anatsui entered the “International Art Circle”, he found that his works were too small, while the contemporary art works were becoming bigger and bigger. During the following 20 years, one of his main tasks was to expand the size of his own works. The use of bottle-tops made it possible. He devoted himself totally to the production of the grand spectacle of contemporary art. In 2007, he exhibited two works Fresh & Fading Memories and Dusasa at Venice Biennale, which were large and were representative for his new style.

And the use of bottle-tops also led to massive low-tech labor. Anatsui compared this kind of procedure with traditional African mode of production, which evokes in us post-colonial imagination.

Furthermore, bottle-tops are wastes, and they are ready-mades as well. As wastes, they remind us of such motif as “Consumer Society”. As ready-mades, they play a significant role in modern art history. This is, again, a legacy of Duchamp. Dramatically, Anatsui interpreted his own works in a way similar to Arthur Danto. He said: “I transform the caps into something else.” He believed that he has “uplift” base materials and elevated them to the status of art. And he compared this transformation to lgbo religious practice, in which an ordinary broken pot is transformed into a spiritual dimension. As a serious scholar, Danto has distinguished the meaning of “transformation”, which was Anatsui’s phrase, from that of “transfiguration”, which was borrowed by Danto from the Christian vocabulary. However, it could not be ignored that both Danto and Anatsui explained their own phrase in a religious way. Apparently, Anatsui used “transformation” to express the same religious and metaphorical significance as Danto’s “transfiguration”: to change the object’s nature without changing its physical status.

With the help of bottle-tops, Anatsui entered the modern art history. When he said: “In 1990 in Venice Biennale I showed as an African artist, … But 16 years after that, I went as just an artist.”, he was absolutely correct. But he did not mean to ignore his African background. In fact, he used to interpret his own works in an ambivalent way. On the one hand, he put his works in the context of African customs, religions, and colonial histories; on the other hand, he denied the similarity between his works and African productions. Obviously, he is not willing to be acknowledged in an Africa-related context, while he knows very well that this is exactly what the western audience expects of him. Is it self-contradictory? No. After all, we have been so familiar with paradoxes that we would never be confused by such a comment: “The African Anatsui is the International Anatsui, while the International Anatsui has nothing to do with Africa.”

The three Others take part in the construction of International Contemporary Art in three kind of ways, defining themselves in the context of modern art history. This is typical for contemporary non-western artists. Clearly, they are the Other without otherness, the Other belonging to the center. However, to acquire a position in the center, they have to put themselves on the border and identify their marginality firstly. This identification should neither be too clear, nor be too vague. Perhaps, the recent revival of Nationalism is positive to some extent. At least, it will show us that not only the Universalism is a failed Utopia, so is the Hybridity.

Zhai Jing

Capital Normal University, Beijing, China

2016.9

[1]Homi K. Bhabha: ”Cultural diversity is an epistemological object – culture as an object of empirical knowledge ……Cultural diversity is the recognition of pre-given cultural contents and customs; held in a time-frame of relativism it gives rise to liberal notions of multiculturalism, cultural exchange or the culture of humanity. …… Cultural diversity may even emerge as a system of the articulation and exchange of cultural signs……” In Homi K. Bhabha, The Location of Culture, Routledge (London/ New York), 1994, p.34.

[2] 安托南·阿尔托,《残酷戏剧》,桂裕芳译,商务印书馆2015年,第69-74页。

[3]在《马拉/萨德/阿尔托》一文中,桑塔格观察到:“阿尔托‘残酷戏剧’……最与之接近的东西,是过去五年间在纽约及其他地方出现的、其参与者大多为画家……的那些没有文本或没有至少可以理解的言语表达的戏剧事件,即所谓‘事件剧’。”苏珊·桑塔格,《反对阐释》,程巍译,上海译文出版社2003年,第200页。

[4] 但德里达反对这种说法,他认为偶发艺术对于残酷戏剧来说,犹如尼斯的嘉年华之于古希腊的俄勒西斯秘仪。它用政治激情代替了阿尔托的完整革命。德里达,《书写与差异》,张宁译,三联书店2001年,第440页。

[5] 斯图尔特·霍尔、托尼·杰斐逊编,《通过仪式抵抗:战后英国的青年亚文化》,孟登迎、胡疆锋、王蕙译,中国青年出版社2015年。

[6]阿布拉莫维奇的许多作品中都使用了矿物,她认为这些神秘的自然物质有助于实现她与观众之间的“能量交换”,这表明了她的创作与神秘宗教之间的关联。例如她做了一系列“无常的客体”,以矿物对应身体的部位:石英是眼睛,紫水晶是智齿,紫水晶晶洞是子宫 ,铁是血,铜是神经……她相信它们能产生使人的意识恢复活力的能量。詹姆斯·韦斯科特,闫木子译,《玛丽娜·阿布拉莫维奇传》,金城出版社2013年,第178页。

[7] 斯拉沃热·齐泽克,《欢迎来到实在界这个大荒漠》,季广茂译,译林出版社2012年,第14页。

[8] 正如齐泽克所言,那些更为悲惨的事件,例如基辛格对柬埔寨的地毯式轰炸杀死了数以万计的人,却是不可见的。斯拉沃热·齐泽克,《暴力:六个侧面的反思》,唐健、张嘉荣译,中国法制出版社2012年,第40页。

[9] 罗兰·巴特,《神话修辞学》,温晋仪译,上海人民出版社2009年,第169-170页。

[10] 马库斯·米森,《参与的恶梦》,翁子健译,金城出版社2012年,第37-39页。

[11] 以赛亚·伯林,《自由及其背叛》,赵国新译,译林出版社2011年,第29-46页。

[12] Donald Kuspit: ”Eighties art is full of much pretence of greatness, of the look of greatness.……The full import of art in the age of the sign is available only through an understanding of operatic, for the operatic makes clear that the essence of the sign, the source of its power, is that it is a pose.”. In Donald Kuspit, Idiosyncrátic Identities: Artists at the End of the Avant-Garde, published by the Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge, 1996, pp.12-13.

[13] 尼采,《瓦格纳事件/尼采反瓦格纳》,孙周兴译,商务印书馆2011年,第24页。

[14] 前引书,第34、46页。

[15] 鲍里斯·格洛伊斯,《走向公众》,苏伟、李同良等译,金城出版社2012年,第66页。

[16] Susan Mullin Vogel: “……and he (Anatsui) began to talk about the use of size as an expressive tool.” In Susan Mullin Vogel, El Anatsui: Art and Life, published by Prestel Verlag, Munich·London·New York, 2012, p.122.

[17] 他最喜爱的四位艺术家是安尼施·卡普罗(Anish Kapoor)、安东尼·葛姆雷(Antony Gormley)、詹姆斯·特里尔(James Turrell)、奥拉夫·埃利亚松(Olafur Eliasson),这或许很好地旁证了他对景观化的自觉寻求。Anatsui: “Artists who have really gotten to me are not figurative – [Anish] Kapoor is one …… Antony Gormley …… And James Turrell, who did Roden Crater. …… Olafur Eliasson……” Quoted in Susan Mullin Vogel, El Anatsui: Art and Life, p.142.

[18] El Anatsui: “I don’t see what I do as recycling: I transform the caps into something else.”, quoted in Sophie Perryer, In the Making: Materials and Process (Cape Town: Michael Stevenson Gallery, 2005), n.p.

[19] 尼日利亚南部的一个种族群体。

[20] Susan Mullin Vogel: “Anatsui speaks of ‘uplifting’ base materials and elevating them to the status of art. ……He compares his transformations to lgbo religious practice, in which an ordinary broken pot is no longer ‘a physical pot, but a pot which has been transformed into a spiritual dimension ……’” In Susan Mullin Vogel, El Anatsui: Art and Life, p.126.

[21] 阿瑟·丹托,《寻常物的嬗变》,陈岸瑛译,江苏人民出版社2012年,第210页。

[22] Anatsui: “In 1990 in the Venice Biennale I showed as an African artists, a geographically defined artist. But 16 years after that, I went as just an artist.” FCC interview with the author, Nsukka, January, 2009. Quoted in Vogel, El Anatsui: Art and Life, p.89.

[23] 这一点在他对非洲织物的态度中体现得特别清楚,一方面,他不断地提及自己对非洲织物adinkra及其象征形式的借用,另一方面,他又特别反感别人将他的作品解读为某种对非洲织物的模拟。而在他自己的命名中,织物的意象却一再出现,如2001年的《女人的衣服》和《男人的衣服》,2003年的《Adinkra Sasa》,2005年的《上流社会女人的衣服》等。

[24] 阿布拉莫维奇特别明白这一点。事实上,她早已经将自己置入了西方主流艺术史,开始了自我经典化的过程。《七个作品片段》中,她将自己与行为艺术的“大师”们并列在一起;她推出了类似《阿布拉莫维奇的生与死》(罗伯特·威尔逊(Robert Wilson)导演)这类景观化的作品;她成立了自己的学院……这些无不在确认着她的经典地位。